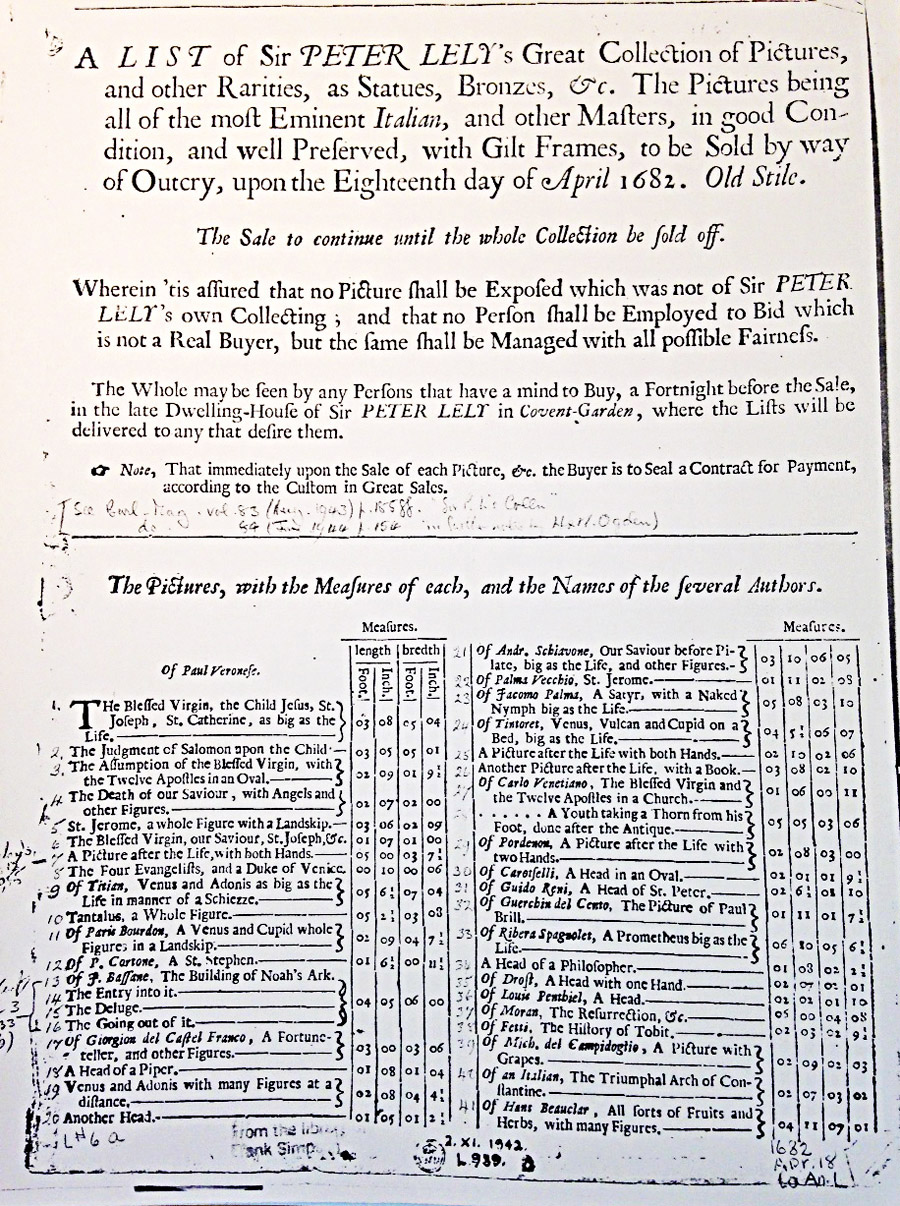

A list of Sir Peter Lely’s great collection of pictures, and other rarities, as statues, bronzes, &c., London, 1682. The Getty Research Institute, photocopy with notes from the library of Frank Simpson. Original manuscript at the National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The Getty Provenance Index has, for three decades, been a leading resource for scholarship on the history of collecting. Founded in the early 1980s by Burton Fredericksen, the first curator of paintings for the Getty Museum, the Provenance Index has evolved into a collection of online databases with 1.75 million records indexing the works of art described in source documents such as auction catalogs, archival inventories, and dealer stock books. This data can be used to trace the ownership of works of art and to examine patterns in collecting and art markets.

A recent project added 138,000 database records for the contents of the first 100 years of British sales catalogs, from the earliest extant catalog—Sir Peter Lely’s 1682 picture sale—up to the year 1780. These database records represent paintings, sculptures, drawings, and miniatures from over one thousand sales.

This project was phase two of a collaboration between the Getty Research Institute’s Project for the Study of Collecting and Provenance and the National Gallery, London, known as British Sales 1780–1800: The Rise of the London Art Market. I offered a detailed description of the project in a previous Iris post. This new phase of the project benefitted enormously from the contributions of Richard Stephens at the University of York, who made available many transcriptions of early sale catalogs and other documentation on the website The art world in Britain 1660 to 1735.

A few collectors had a major impact on the early art market in Britain. One was King Charles I. The dispersal of his collection after his execution in 1649 acted as a catalyst for the burgeoning British art market. A few decades later, in 1682, the sale of Sir Peter Lely’s collection ushered in the rise in popularity of selling art at auction in Britain, which had previously been done mainly by lottery or private sale.

Another influential seventeenth-century collector was Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel. He has been described as the greatest collector of his time apart from Charles I. He was a great patron of the arts and commissioned portraits from the best painters of the day. In honor of the collaboration between the Getty and the National Gallery, I thought I would highlight two of these portraits (shown below), records for which can be found in the Getty Provenance Index databases.

The first is a portrait by Peter Paul Rubens, which appeared in a Langford sale on March 20, 1754 (Provenance Index Br-A479, lot 40). It was sold by the collector Dr. Richard Mead to Lord Carlisle for £36.15, and the painting was passed down through the Earls of Carlisle until the twentieth century. In 1914 it was presented as a gift from Rosalind, Countess of Carlisle, and is now in the collection of the National Gallery, London.

Left: Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel, 1629–30, Peter Paul Rubens. Oil on canvas, 67 x 54 cm. National Gallery, London, Presented by Rosalind, Countess of Carlisle, 1914. Photo © The National Gallery, London. Licensed under an Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license. Right: Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel, ca. 1620–21, Anthony van Dyck. Oil on canvas, 102.6 × 79.7 cm. The J. Paul Getty Museum. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

The second is a portrait by Anthony van Dyck. It has a more complicated provenance, moving back and forth between Britain and France before finally coming to America. It was given by the Earl of Arundel to George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, but by 1723 it was part of the collection of the duc d’Orléans in France. The dealer Michael Bryan bought it in Paris and then sold it at auction in London in 1801 to the Duke of Bridgewater, for 400 guineas (Provenance Index Br-62, lot 92). After that, the painting passed through several collections, eventually coming to its current home at the Getty Museum in 1986, bought from the dealer Thomas Agnew & Sons.

While the provenance of these two portraits was already known, we hope that the newly added sales records will assist in reconstructing ownership histories such as these for many more artworks.

Case Study: Comparing the Early British and French Art Markets

With the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century sales data newly added to the Provenance Index through this collaboration, British sales coverage now extends from 1682 up to the 1840s. The British sales data is also searchable alongside records for French, German, Dutch, Belgian, and Scandinavian sales. This will enable scholars to look for patterns both within and across national art markets.

As an example, let’s look for points of comparison between British and French art sales of the eighteenth century. There are relatively few French sale catalogs for the first half of the 1700s, so we’ll focus instead on the second half of the century.

One way to analyze the relationship between the art markets of France and Britain is to track the number of artworks appearing in sales over time. As you can see in the following graph, the number of artworks appearing at auction in Britain and France rose mainly in tandem until the mid-1770s, when the French market suddenly dominated. The situation changed around 1789, at the outset of the French Revolution, after which the British market was dominant.

One interesting note: the total number of artworks appearing in sales in France and Britain was almost the same during the French peak in 1779 and the British peak twenty years later. While you can see in the graph that the difference between the two markets was dramatic during those two periods, the combined number of artworks—about 12,000 in 1779 and 11,000 in 1799—was remarkably close. This indicates that the overall art market remained relatively stable and simply shifted from France to Britain during the French Revolution.

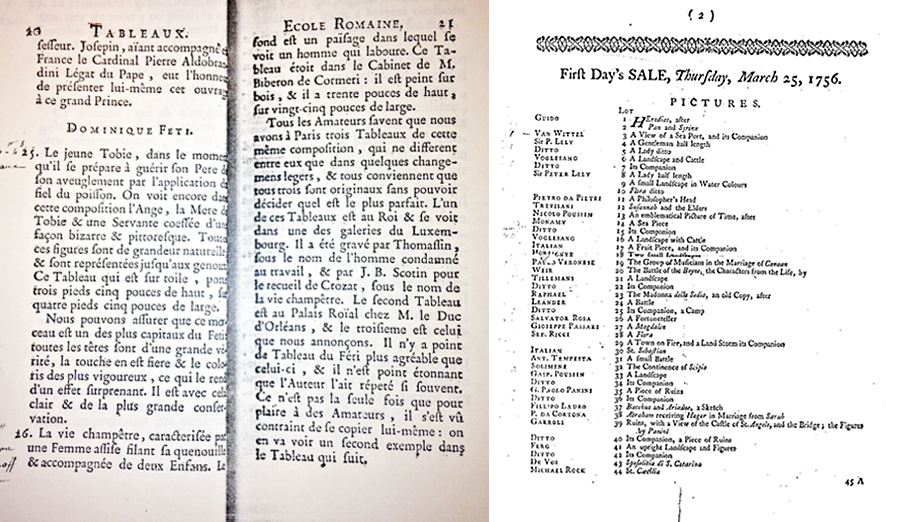

These numbers suggest an interconnectedness between the markets of France and Britain, but French and British auction catalogs developed as distinct literary forms. The laws regarding auctions were different in the two nations and this affected the relationships between dealers and auctioneers, which in turn affected the style of the catalogs. In France the catalog entries were generally written by connoisseurs, who often provided lengthy descriptions and imposed value judgments. Increasingly in the second half of the 18th century, these French connoisseurs emphasized the importance of the artist attributions, separating painting entries by artistic school (French, Italian, Dutch and Flemish, etc.), and segregating copies and paintings with questionable attribution at the end of the sections.

The typical painting description in the British catalogs, on the other hand, was very short and simply described the main subject. Instances in which a British auctioneer would expound the artistic merit of a painting or provide support for its authenticity were less common. It is clear that many paintings listed under an artist’s name were actually copies or were painted by less esteemed members of the same artistic school. The following examples, both from 1756, illustrate the difference between French and British catalogs. Notice that the French example has placed the artist in a section for “Ecole Romaine” (Roman School), while the entries in the British example do not look much different from that of the first British catalog of 1682:

Left: Catalogue raisonné des tableaux, sculptures, tant de marbre que de bronze, desseins et estampes des plus grands maîtres, porcelaines anciennes, meubles précieux, bijoux, et autres effets qui composent le cabinet de feu monsieur le duc de Tallard. Remy & Glomy, Paris, March 22, 1756. Right: A catalogue of the genuine and curious collection of pictures, by several eminent masters, of that ingenious architect James Gibbs, Esq. Mr. Langford, London, March 25, 1756

To test the theory that the authors of the French catalogs were more interested in issues of authenticity than their British counterparts, we can look at the Provenance Index data for 1750–1800 and see if we can learn anything about how the paintings were attributed. Surprisingly, the percentage of anonymous paintings is almost exactly the same in French and British sales, about 3%. But a check for paintings with attributions such as “copy,” “school,” “manner,” “style,” and so on reveals something interesting. The French records are twice as likely to have these attributions, at 8%, compared with 4% in British sales. That does not tell us definitively that the French attributions were more accurate—it’s theoretically possible that the British sales included a higher percentage of originals—but it does provide a clue about the care taken with attributions.

The new records added to the Provenance Index provide countless opportunities for comparison. For example, we can see how many paintings include dimensions in their catalog descriptions. It turns out that there is a significant difference between the French and British catalogs in this regard, too: 49% of the French records for the period 1750–1800 include dimensions, while only 7% of the British records from the same time period include this information.

We’ll end with an example of the different levels of description for French and British audiences. The Swiss portrait painter Jean-Étienne Liotard brought his collection of old master paintings to London in 1773 and put them on display for sale, along with several of his own paintings (Provenance Index Br-A921-A). There were French and English versions of this catalog, and he probably wrote the entries himself. The difference in the level of detail between the two versions is almost comical. Here are the French descriptions for a pair of paintings by Jan Brueghel the Elder and Joos de Momper:

It’s possible he was a little tired after writing those, because the English entries are a bit more concise:

The 1773 exhibition did not produce many sales, so these two paintings, along with most of the rest of the collection, were sold at auction the following year at Christie’s (Provenance Index Br-980). This time Christie’s provided the description, and it was even more in the English taste:

Momper, Brugael 79 A bleach yard with a number of figures busily employed Ditto ———– 80 Harvest its companion

The French titles could be describing the following pictures in the collection of the Museo del Prado, Madrid. However, the Prado pictures are thought to have been in the Spanish royal collection prior to the Liotard sale, so perhaps they are versions of the same subjects.

This is just a taste of the kinds of discoveries and data comparisons that we hope the new British sales data will enable. To explore this new data, choose “Sales Catalogs” within the Provenance Index search interface.

Left: Market and Bleaching Ground, ca. 1620, Jan Brueghel the Elder and Joos de Momper II. Oil on canvas, 166 x 194 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid. Image: Wikimedia Commons. Right: Grain Harvest, 1620–22, Jan Brueghel the Elder and Joos de Momper II. Oil on canvas, 166 x 168 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid. Image: The Brueghel Family Database, University of California, Berkeley

Comments on this post are now closed.