A new installation in Gallery W101 at the Getty Center presents 18th-century Neoclassical sculptures alongside two Roman pieces with storied pasts

Who’s the fairest, Venus, Minerva, or Juno? The contest is happening at the Getty Center, in the galleries of the West Pavilion, through an unprecedented display mixing antiquities with 18th-century sculptures.

The contest all started because Jupiter did not invite the goddess of discord, Eris, to the wedding banquet he organized for Peleus and Thetis (but frankly, who would have?). Offended, Eris invited herself to the feast, and cast a golden apple marked “to the fairest” among the assembled goddesses. Immediately, three of them laid claim to the fruit: Venus, Juno, and Minerva. Jupiter was asked to mediate, but couldn’t do much—after all, Juno was his wife!

Hoping to avoid a quarrel, Jupiter decided that the young shepherd Paris, prince of Troja (Troy), would decide. When brought in front of Paris, the three goddesses did their best to gain the shepherd’s preference. Paris eventually gave the apple to Venus, who had promised him as a reward Helen, the most beautiful mortal woman. But when Paris took Helen, the tragic war between the Trojans and the Greeks broke out.

This very famous Greek myth of the Judgment of Paris has been depicted in art since ancient times, and was well known to any educated person in modern times—such as Charles Watson-Wentworth, second Marquess of Rockingham. One of the wealthiest men and keenest collectors of sculpture in Britain in the 18th century, he acquired an ancient statue featuring Paris and then commissioned from his favorite sculptor, Joseph Nollekens, three statues of goddesses to accompany it and complete the narrative of the famous Judgment.

Nollekens’s three marble goddesses: Juno (1776), Venus (1773), and Minerva (1775). The J. Paul Getty Museum, 87.SA.108, .106, and .107

You have to see the sculptures in person—all installed in Gallery W101—to understand how seriously the goddesses take the contest. When you enter the gallery, Juno is staring at you, as if calling on you to tell Paris that she is the fairest. She has already unveiled one breast and is about to remove her dress. Next to her, perched on a tree stump in a relaxed posture, is Venus, who has been even faster at the competition: completely naked, she is slipping off her remaining sandal. She looks self-confidently at Paris, anticipating the moment he’ll turn his attention to her and be caught by her beautiful curves. Meanwhile, the young prince is still examining Minerva. Fully dressed, her shield leaning against her leg, she hesitates to take off her helmet…is she too shy to disrobe, or is she crestfallen by her impending defeat by Venus? It is up to each visitor to interpret this unique group Nollekens conceived.

Without question the three goddess statues, carved in renowned pure white Carrara marble, are masterpieces. The sculptor masterfully composed them as a group: the figures naturally “dialogue” together, “move” with ease in the space with a broad variety of poses. And I can’t fail to mention his skill at rendering the soft fabric of the goddesses’ dresses, the shiny metal of Minerva’s helmet and shield, the flesh glowing like satin, the smooth lace of a sandal!

Paris, Roman, 2nd century A.D with 18th-century additions. Marble, 52 3/8 in. high. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 87.SA.109

One can hardly say the same about the statue of Paris, however. Though he does have a seductive, genuine face framed by delicately carved locks of hair, he suffers from a patchworked appearance, yellowed marble, and a stiff pose. The sculpture is thought to represent the shepherd Paris because of his youthful appearance, the style of his cap, and the staff and apple he holds. But the head most likely belonged to another ancient body, and the two arms are modern additions from sometime before the middle of the 18th century. Because of all these factors, it was previously not exhibited in our galleries, but kept in storage.

Paris holds the golden apple awarded as a prize to the fairest goddess in the Judgment of Paris

So why display him now? Unavoidably, in displaying their collections museums make choices. Until this new display, the Paris statue wasn’t considered to be of high enough aesthetic quality to be shown. Fair enough. But let’s look at the issue from another point of view. This ancient statue, albeit heavily restored, was much praised in the 18th century, not only by Lord Rockingham but also by its previous owner, Lyde Browne. Two drawings featuring the statue, one by Pietro Cipriani (the creator of the Medici Venus and Dancing Faun exhibited in the same gallery), attest to artists’ interest in the figure. More importantly, the statue was published by the father of art history, Johann Joachim Winckelmann, in his 1767 book Monumenti antichi inediti, with the proposal that it had been wrongly restored and was not originally Paris. (The Getty Research Institute keeps a copy of this very book its special collections holdings.) In antiquity, the statue may have indeed represented a cult servant holding a sacrificial animal, which would explain the patch on the stomach. Last but not least, the Paris is an integral part of the origin of the group created for Lord of Rockingham by Joseph Nollekens to form a Judgment of Paris “installation” that begged to be displayed in its entirety.

Now, we thought, since our curatorial choices for this installation were no longer just aesthetic but also focused on the history of taste and collecting, let’s be consistent and remove from storage another work of art that also belonged to the Lord of Rockingham. Because this new display also tells us a lot about how works of art, dispersed at one moment of their history, can be reunited later. The above-mentioned three goddesses and the Paris statue, along with two busts by Joseph Wilton and two statuettes attributed to his workshop, were acquired in 1987 by the J. Paul Getty Museum after the 1986 sale of Wentworth Woodhouse. But at that time the Museum’s holdings already contained a piece from Lord Rockingham’s collection: a marble relief purchased by J. Paul Getty in 1953, a few years after the first sale of the same estate organized in 1949.

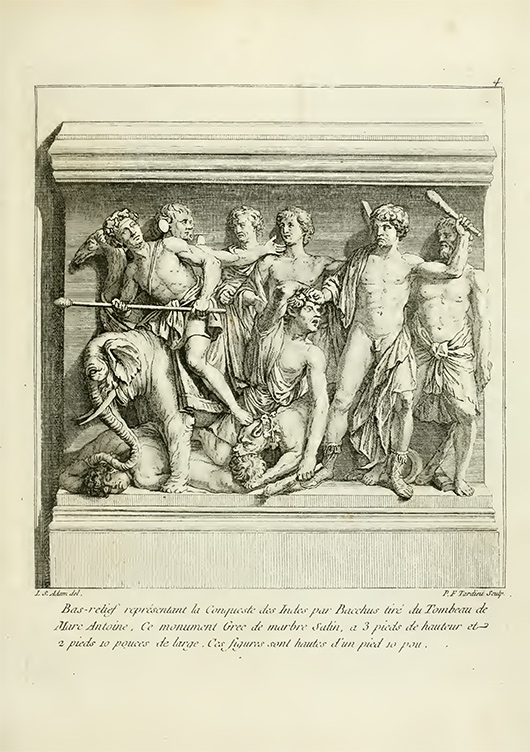

The Triumph of Bacchus, Roman, 2nd century with 18th-century restorations. Marble, 37 3/16 x 37 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 78.AA.61

The peregrinations of this relief, The Triumph of Bacchus, from Italy to England via France, wonderfully document the history of taste for the antique in the 18th century. Discovered in Rome between 1728 and 1730, it belonged to Cardinal de Polignac, the French ambassador in Italy, who conducted many excavations in the Eternal City. Polignac was a key figure in high society and in the collectors’ and antiquarians’ circle in Rome. The relief, with the cardinal’s collection, was brought to Paris in 1731 and at the cardinal’s death in 1741 was given to the sculptor Lambert-Sigisbert Adam as partial payment for the work he had done for Polignac. Adam, a celebrated French sculptor, had begun working for the cardinal as a restorer of ancient sculptures when he was a fellow at the French Royal Academy in Rome.

In 1755 Adam published a Recueil of the ancient sculptures he had in his atelier, in large part drawn from Polignac’s collection, with the aim of selling the objects. The engravings in this summary were printed after his own drawings of the objects, complete with titles and dimensions. And guess what? An edition of this book belongs to the Getty Research Institute, and plate 4 illustrates the relief bought by J. Paul Getty, with the restorations done by Adam. The relief was still in his possession at his death in 1759 since it is listed in the inventory of his collection. The Triumph of Bacchus was sold in 1763 or 1764 when the sculptor’s estate was dispersed, and was most likely purchased at that time by Lord Rockingham.

Plate representing the relief The Trumph of Bacchus, Roman with 18th century restorations by Lambert-Sigisbert Adam. Engraving in François Joullain, Collection de sculptures antiques, grecques et romaines…, 1755. The Getty Research Institute, 86-B23543

The 18th-century restorations are clearly visible, but they are precisely what makes the relief intriguing. For instance, one can easily distinguish the ancient head of the man lying under the elephant from the other modern heads carved by Adam, whose style is easily identifiable when compared to other sculptures by his hand.

The Triumph of Bacchus relief and the Paris statue may not be masterpieces as we conceive them with our 21st-century eyes, but it is the fascinating stories they tell that can excite visitors’ and art historians’ curiosity. I confess, there are mysteries that still need to be unraveled. What is the I.B. inscription on Paris’s back, for instance? And what about the strange head in the middle background of the relief that that looks like a portrait, and is the only one executed in plaster?

We will keep you posted. We Getty curators and conservators, from both the Sculpture & Decorative Arts and the Antiquities teams, will carry on searching and studying. Traffic on Sunset Boulevard between the Getty Center in Brentwood and the Getty Villa in Malibu will never prevent us from working in close collaboration! And needless to say, colleagues and scholars coming from all over the world to Los Angeles may also help us, since they can now easily access these works of art in the West Pavilion.

Most importantly, the narrative of Neoclassicism we tell in our galleries is complemented and deepened by both Paris and the Bacchus relief, which are prime examples of the appropriation of ancient fragments at the hand of 18th-century sculptors and restorers. Reuniting all of these nine sculptures from Lord of Rockingham’s collection together lends the gallery a new level of authenticity achieved through the perspective of this eminent taste-maker of the period, rather than curatorial authority alone.

Venus casts a beguiling glance at Paris in Gallery W101

Comments on this post are now closed.