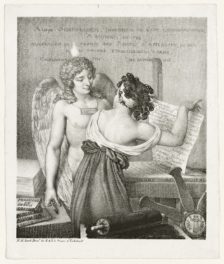

The Admiral of France / De France Admiraal, 1702, unknown artist. Etching, 29.6 × 19.3 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France

King Louis XIV, aptly advised by his ministers, understood very early the importance of engravings in showcasing his actions, his court, and his reign. He created the Cabinet du Roi within the Bibliothèque royale in 1667 to collect engravings and print works commissioned from the best printmakers, and to distribute them to important figures of the time. Meanwhile, many private publishers publicized the glory of their king—consciously or not.

The king’s enemies, however, had wit to match, and throughout his reign prints from opposing factions echoed and answered each other, often using the same themes and symbols, and sometimes amusingly twisting them.

The king’s enemies, however, had wit to match, and throughout his reign prints from opposing factions echoed and answered each other, often using the same themes and symbols, and sometimes amusingly twisting them.

The king’s most famous symbol was the sun, which Louis XIV did not create but used extensively. Opponents of the Sun King happily cherry-picked the classics for episodes in which the comparison is less than flattering: Joshua, Icarus, and Phaeton (the son of Helios, who lost control of his father’s sun chariot and was killed by Zeus before he crashed it to earth and burned the world) feature heavily.

Sun-themed counterpropaganda could be very clever. It produced powerful parallels, like the 1692 print mocking the sinking of the warship Soleil-Royal (“royal sun”) by the Anglo-Dutch coalition, “destroyed before he could set the world on fire.” The piece denounces “the raging tyrant’s dire insolence / who boasts the sun himself as his banner” (« ce tyran furieux dont l’insolence extrême / s’est bien osé choisir le soleil pour emblème »).

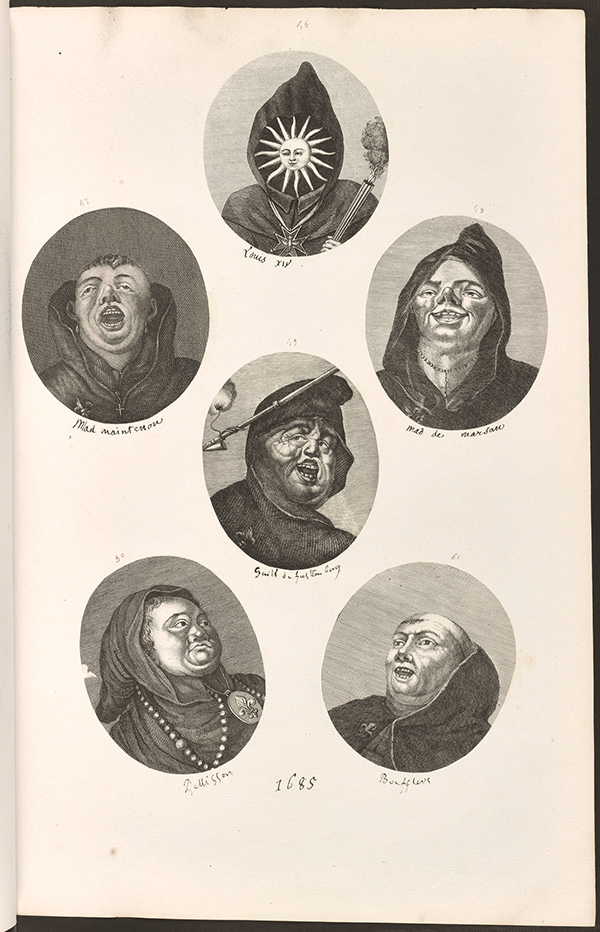

This anti-French imagery was not solely meant to debunk the king’s propaganda: other publications, too, were part of a global effort to mock the French court and oppose its politics. A good example of this is the famous work called Les Héros de la Ligue, published in Amsterdam in 1691 and containing sixteen caricatures of figures of the anti-protestant repression in France.

Page from Les Héros de la Ligue, Paris (i.e. Amsterdam) in the print collection Monumens de l’histoire de France, vol 68. The Getty Research Institute, 900247

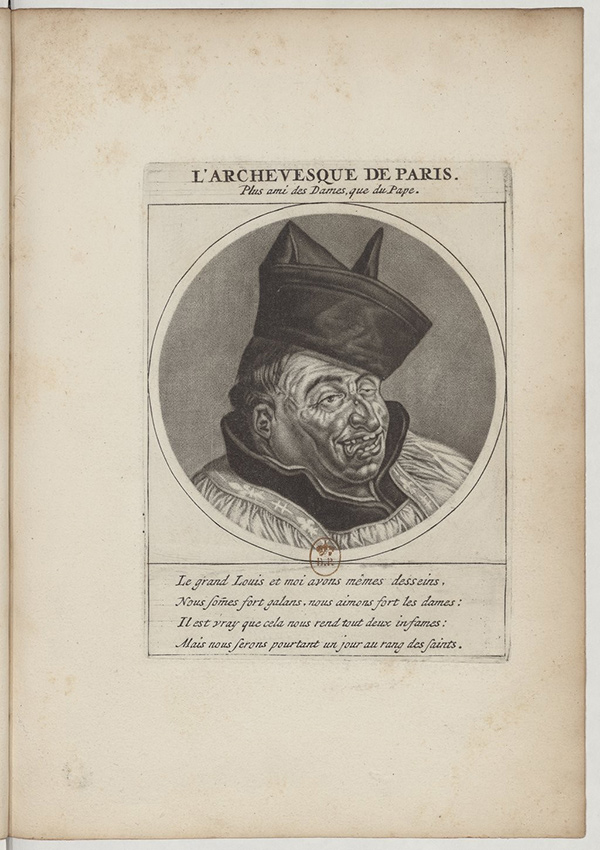

The Archbishop of Paris (Fr. Harlay de Champvallon), 1691, Cornelis Dusart (?) or Jacob Gole (?). Mezzotint in Les Héros de la Ligue…, Paris (i.e. Amsterdam). Bibliothèque nationale de France

They include the king, his minister of war Louvois, the archbishop of Paris, and the famous scholar and bishop of Meaux, Bossuet. They are all depicted as drunkards and profligates who advance their own political agenda with no actual regard for religious matters. The prints are anonymous mezzotints but are attributed to some of the best engravers of the time, Cornelis Dusart and Jacob Gole among others. They were so successful that they were reproduced as burin engravings such as the very rare print (shown above) in the collection of the Getty Research Institute.

This production was not solely the work of professional printmakers, and the counterpropaganda was not a unified attempt with a clear strategy: many actors were involved, from the powerful to the most common. For instance, when Louis XIV banned Protestantism in 1685 and had Paris’s temple destroyed, worshippers made a print representing the Sun King as the devil, in a desperate attempt to appeal to the world at large and gain support for their cause.

Destruction of the Protestant Church of Charenton, 1685, unknown artist. Engraving, 19.5 x 14.8 cm. Bibliothèque nationale de France

This very crude and naive image conveys the strong emotions of simple individuals about what they saw as a profound injustice.

Aside from its quality and its religious and political significance, this piece shows the strength of such imagery based on more-or-less complex symbolism, and how it could reach a large audience. And although the concept of “public opinion” was barely formed at the time, and Louis’s administration tried to maintain strict censorship, the means were certainly there to make the public laugh, to move, to touch… and maybe even to convince.

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks