Victoria Reed of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) sleuths art for a living. She researches provenance—a vast and complex field that includes where artworks have been, who’s owned them, and when, where, why, and how they’ve changed hands. Her realm is the MFA’s vast collection, as well as objects curators are considering adding to it. Archives, libraries, and even Google Books are her gumshoe go-tos.

Victoria Reed of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) sleuths art for a living. She researches provenance—a vast and complex field that includes where artworks have been, who’s owned them, and when, where, why, and how they’ve changed hands. Her realm is the MFA’s vast collection, as well as objects curators are considering adding to it. Archives, libraries, and even Google Books are her gumshoe go-tos.

In anticipation of her talk at the Getty Center next Thursday, I asked her to reveal her methods and name an art mystery she’d love to see solved.

A curator’s work typically includes researching the provenance of objects; how did you come to specialize in this one facet of a curator’s duties?

I came to specialize in provenance research by accident. While I was in graduate school, I worked part-time at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, helping to catalogue European paintings. This included compiling exhibition history, bibliography, and provenance—as you say, typical curatorial duties.

By the late 1990s, following the Washington Conference on Holocaust Era Assets in 1998, and the issuing of provenance research guidelines by the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) and Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), there was a push at American museums to conduct more in-depth research on Nazi-era provenance. I worked at the Princeton University Art Museum from 2001 until 2003; there, one of my duties was to research the provenance of the European painting collection. The full-time provenance research job opened at the MFA in 2003.

Can you give us a day in the life of an “art detective”?

Actually, there is no typical day. Some days I’m at my desk looking at the paperwork for potential acquisitions. Some days I’m at the MFA’s library or archives, or at the libraries at Harvard, conducting research. Some days, like everyone else, I’m in meetings or running from appointment to appointment between answering emails.

Has technology made it easier to determine the origin of a work of art? For example, is there a large difference between how the research is done now compared to 20 years ago?

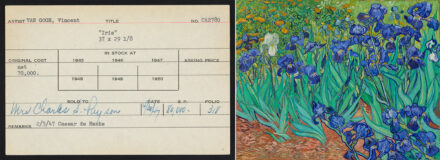

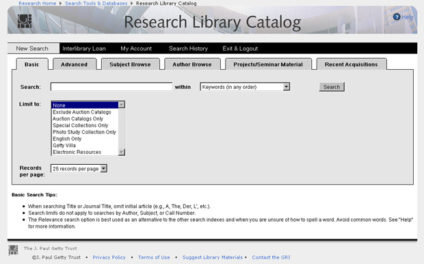

Yes—even compared to 10 years ago! There are so many more research tools available online now than there were when I started. Between digitized records, Google Books, JSTOR, and online databases (not least of which are the ones the Getty maintains), many parts of the research process are faster than they used to be. Many auction results are available online; and sites like Fold3.com and Ancestry.com have become indispensable in my work.

Also, as libraries and archives develop stronger web presences, it has become easier to locate resources than it used to be. Of course, it’s still critical to know how to use a library, load a microfilm reel, and utilize archival records. Not everything is online or digitized.

Have digital archives been useful to you?

Yes, in large part. For example, when the National Archives and Records Administration made some of their most widely utilized records accessible in 2011 (via Fold3.com), it meant I could get quick answers to many of my questions without having to wait until I next traveled to Washington, D.C.

What is your primary focus at the moment?

Since I work with each curatorial department [at the MFA] now, it’s hard to pick just one. I still continue to devote a lot of energy to the art of Europe. I also work quite a bit with prints and drawings, and the arts of Asia, Africa, and Oceania.

Is there an object in the MFA’s collection (or another collection) that has remained a mystery to you?

Portrait of a Man and Woman in an Interior, 1665–67, Eglon van der Neer. Oil on panel, 29 1/8 x 26 5/8 in. (73.9 x 67.6 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 41.935

There are lots of objects whose histories I’d love to know more about. In my lecture on Thursday, I’ll discuss Eglon van der Neer’s Portrait of a Man and Woman in an Interior, which belonged to Walter Westfeld, a Jewish art dealer in Nazi Germany. There is a significant gap in its provenance—between 1936, when it was last documented in Nazi Germany, and 1941, when the MFA bought it on the New York art market. I researched the painting for years; ultimately the MFA determined it had to have been lost or sold under duress by Westfeld, and we reached a financial settlement with his estate and heirs for it. It would, however, be very satisfying to know how the painting made its way to the U.S.

Text of this post © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved.

Details and reservations for Victoria Reed’s talk are here.

I have an art mystery. In 1980 or thereabouts I was commissioned by Emil White to do two portraits.

One of Henry Miller and one of Emil. The Miller painting seems to be hanging in the Henry Miller Memorial Library in Big Sur and the White painting is nowhere to be found. The Miller painting appears to have had the sides cropped off, the right was where my signature was and a signature that seems to say Clarke added to it. I contacted the Miller Library and they attribute the painting to Catherine Foster.

Now Catherine Foster, the artist, does painted metal wall sculptures. From the information the Miller Library gave me I think they are talking about Katherine Foster Clarke who died in 1990. Two things stand out. One on all the work by her, I can find, her full name is spelled out, except for the Miller painting. Secondly neither of these artists paint/ed portraits as far as I can ascertain. Determining the actual provenance of that painting and sorting this out requires a real art detective.