A Bonnacon (detail) in the Northumberland Bestiary, about 1250–60, unknown illuminator, made in England. Pen-and-ink drawing tinted with body color and translucent washes on parchment, 8 1/4 × 6 3/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 100, fol. 26v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Meet 19 animals of the medieval bestiary in Book of Beasts, a blog series created by art history students at UCLA with guidance from professor Meredith Cohen and curator Larisa Grollemond. The posts complement the exhibition Book of Beasts at the Getty Center from May 14 to August 18, 2019. —Ed.

The bonnacon is quite an amusing animal of the medieval bestiary, a type of European manuscript filled with images of animals mythical and real, common and exotic. Almost all of the animals in the bestiary are associated with a Christian moral allegory. The bonnacon is set apart from these, however, because it has no moral attached to its story: its representation is purely comical.

You may never have heard of the bonnacon, but it has had a lasting effect, even playing a role in popular contemporary films.

A Horned, Fearsome Beast

The bonnacon is a mythical, bull-like beast with the mane of a horse and horns that spiral inward on top of its head. The bonnacon’s curved horns are not effective for defending itself against hunters, so instead it shoots a stream of potent dung that can burn anything in its path. In manuscripts the attacking hunters are depicted either with full armor, or just spears and shields, to defend themselves from the robust excrement.

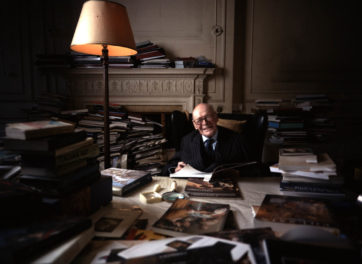

What makes the medieval story of the bonnacon comical is the visual representation of the hunt in bestiary manuscripts. The hunters’ facial expressions are often quite amusing, with eyes big and fearful, and lips in worried straight lines. In the image below (also at the top of this post) from the Northumberland Bestiary, the hunter’s wide eyes and pressed lips show his trepidation.

A Bonnacon (detail) in the Northumberland Bestiary, about 1250–60, unknown illuminator, made in England. Pen-and-ink drawing tinted with body color and translucent washes on parchment, 8 1/4 × 6 3/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 100, fol. 26v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

In representations of the same bonnacon scene in other bestaries, the hunter’s nose is scrunched up at the smell of dung in a mix of disgust and fear. The hunter’s feet often face away from the bonnacon, as if ready to run away—he is fully aware of the gross, sticky situation he could soon be in.

In other manuscript representations, the bonnacon is depicted with its head low and a downturned lip of shame, or a smirk full of mischief as it shoots its fiery fury at the hunters.

The image below from the Harley Bestiary in the British Library shows the next step: the hunt is in progress, and the bonnacon is being slain through the neck by the spear of the hunter. It has a sad facial expression with downturned, mournful eyes.

A Bonnacon (detail) in a bestiary, about 1225–50, unknown illuminator, made in England. Pigment on parchment, 30.8 x 23.2 cm. The British Library, Harley Ms. 4751, fol. 11. Digital image: British Library

The illuminator used strong colors to depict the bonnacon’s special features: the curved horns and mane are a brilliant green, the shooting manure a variety of bombastic colors.

An Alternative Interpretation

Both of these images present the interpretation that the bonnacon shoots fiery feces. However, there is an alternate translation of the Latin Second-family Bestiary—a variation of the bestiary text most often used as a basis for illuminated books of beasts—by Willene B. Clark that sheds a different light on the bonnacon’s story. In this translation, the bonnacon emits a “fart” three acres long to discourage its pursuers. Images in some bestiaries show hunters with their heads turned away from the bonnacon and even covering their nose in disgust to block out the horrible smell of the animal’s gas.

The debilitating “wind” emitted by the bonnacon might have been the inspiration for some of our contemporary film characters, such as Pumba the pig from Disney’s The Lion King. Pumba is known for his blast of smelly gas that’s so potent it causes everyone around him to pass out. In the movie, Pumba’s fart works as a defense mechanism, while still serving as the comic relief of the film, much like the bonnacon within the medieval bestiary.

It appears that beastly bathroom humor has provided comic relief for centuries, from Christian manuscripts to pop-culture movies. Even people in the Middle Ages weren’t immune to the charms of a poop joke.

Further Reading

Clarke, Willene B. A Medieval Book of Beasts: The Second-Family Bestiary: Commentary, Art, Text and Translation. New York: Boydell & Brewer Ltd., 2006.

Gravestock, Pamela. “Did Imaginary Animals Exist?” In The Mark of the Beast: The Medieval Bestiary in Art, Life, and Literature, edited by Debra Hassig, 119–30. New York: Garland, 1999.

Hassig, Debra. 1990. “Beauty in the Beasts: A Study of Medieval Aesthetics.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 19–20: 137–61.

Text of this post © Abigail Ahlers. All rights reserved.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.