July 14 marks the 150th anniversary of Gustav Klimt’s birth, an event celebrated by exhibitions and events in Vienna and right here at the Getty, with Gustav Klimt: The Magic of Line. This summer, we are in the grips of all-out Klimt-o-mania.

I’ve long noticed a passion for all things Klimt. His paintings appear on mugs, dresses, posters, figurines, lighters, pillows, t-shirts, mouse pads, jewelry, ties, vases, skateboards, even a Barbie Doll. Klimt has even taken over Google. But Klimt isn’t just a merchandising hero—people love Klimt. While visiting the Belvedere Palace in a humanities course in college, I witnessed two girls crying in front of Klimt’s The Kiss. These girls were sobbing.

I find the commercialism and pop-culture status that surrounds Klimt’s most famous works—especially those of naked or psychologically vulnerable women—to be almost a moral question. From a female perspective, I wonder: Do we love Klimt too much?

Many of Klimt’s paintings, as well as his erotic drawings and preparatory sketches, suggest a highly intimate relationship to the model and the idea of the “muse.” Some of his models, in fact, bore the artist children out of wedlock. Yet in Viennese society around 1900, women were not seen as creative beings by nature. Viennese journalist Karl Kraus wrote, “The lust of the male draws sustenance from the sterile mind of woman…Here the woman conceives what the man bore.”

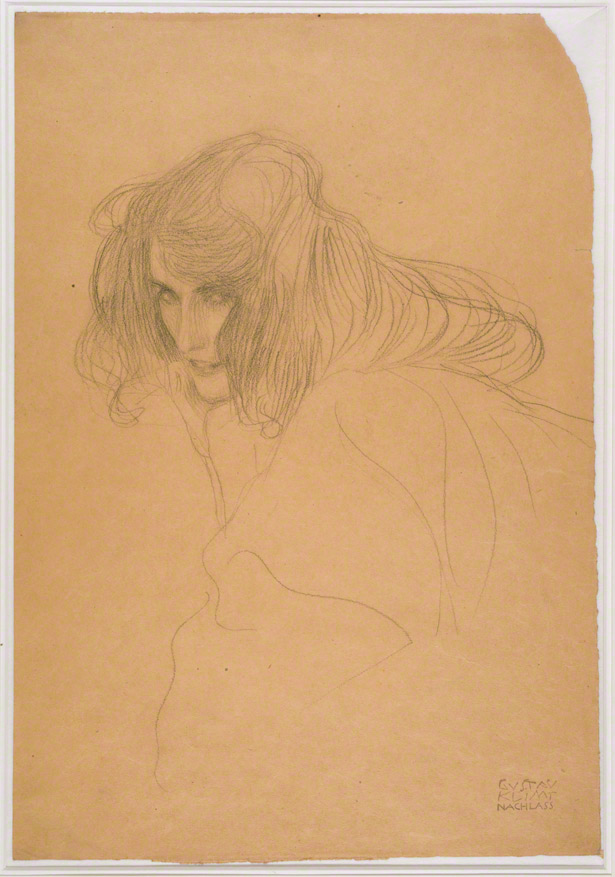

Study for the Figure of “Lasciviousness” (Beethoven Frieze), 1901, Gustav Klimt. Black Chalk. Albertina, Vienna, Gift of Elisabeth Lederer

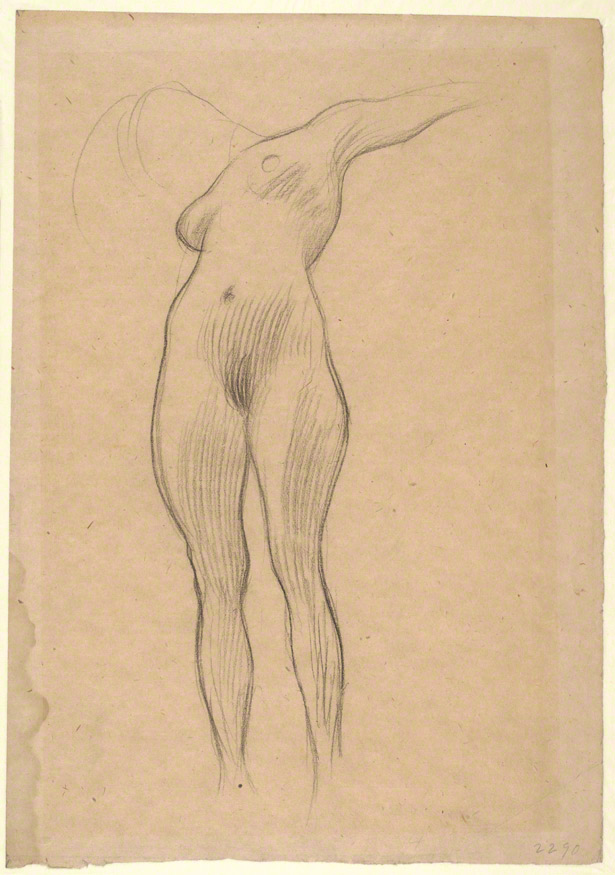

Is this the mindset that motivated Klimt’s drawings of women’s deeply intimate and psychologically complex moments—of sexual release, of self-pleasure, and delicate ages in life such as pregnancy, infancy, old age? Floating women were another recurring motif. Art historian Peter Selz wrote that Klimt “drew these poses with overt, but delicate, emphasis on the genital areas. These drawings were private notes of the artist and have not been shown publicly until fairly recently.”

Lee Hendrix and Edouard Kopp, curators of the Getty exhibition (with Marian Bisanz-Prakken of the Albertina in Vienna), propose a different way of looking at Klimt’s drawings of women. They write that Klimt’s drawings were a way to transport the viewer into the female world on their own, at an utter remove from the male world of action and engagement.

Floating Woman with Extended Arm (Study for Medicine), 1900-1901, Gustav Klimt. Albertina, Vienna

Edouard told me that, in his view, Klimt understood women very deeply. “He created icons out of them. Sometimes ambitious or difficult icons, but powerful figures nonetheless.” These drawings may be acts of power over women, but they are also acts of empowerment for them.

This very psychological complexity, this combination of empathy and distance, is in my view one of the things that explains the cult of Klimt. His paintings and drawings reveal that he had a deep feeling for what it means to inhabit a mortal body, an understanding that makes themes that might otherwise seem cliché (birth, death, reproduction) feel overwhelmingly meaningful. “Klimt’s work touches so many people because he doesn’t discuss trifles, but rather deep, elemental situations that touch every human being, because it is what we share,” expressed Edouard. Every human being—man or woman.

Does the Klimt merchandise diminish any of this? Edouard sees the over-reproduction of Klimt’s works as a kind of “clumsy embrace. If you embrace too much at once, what are you really holding?” It’s a real question to consider when it comes to the reproduction of artists’ work in the age of the Internet—so many artworks are pale shadows of their physical selves in poor reproductions on mugs, t-shirts, and key chains. But these items are still tokens of the works’ power. “I think the effect of a powerful image shouldn’t be repressed,” added Edouard, because “people will always have a need for that image. So I respect and try to understand the need for people to have Adele Bloch-Bauer puzzles. But of course, nothing can replace the experience of the original.”

Klimt reproductions and objects are a way to bring the ever-elusive artist into our daily lives. Though they may obstruct our view of the original, they maintain our emotional connection with his work.

And in this anniversary year, that connection is everywhere. In addition to the Klimt books, collectibles, and more for sale in the Getty Store, the Getty Center Restaurant is featuring a Niman Ranch pork schnitzel and a three-flight Austrian beer tasting, so you can experience even more heights of ecstasy while paying homage to the artist.

The Getty isn’t the only institution getting its Klimt on in this year of celebration. Ten Viennese museums are hosting special exhibitions of his work, Künstlerhaus Wien has prepared a musical celebrating his life, and the Neue Galerie’s Café Sabarsky in New York City has prepared a special chocolate cake with gold leaf in his honor.

Have you given yourself to Klimt-o-mania yet? What are your thoughts on the cult of Klimt? Come see Gustav Klimt: The Magic of Line—look at Klimt’s art in the flesh—and tell us what you thought, what you felt, whether you sobbed.

Comments on this post are now closed.