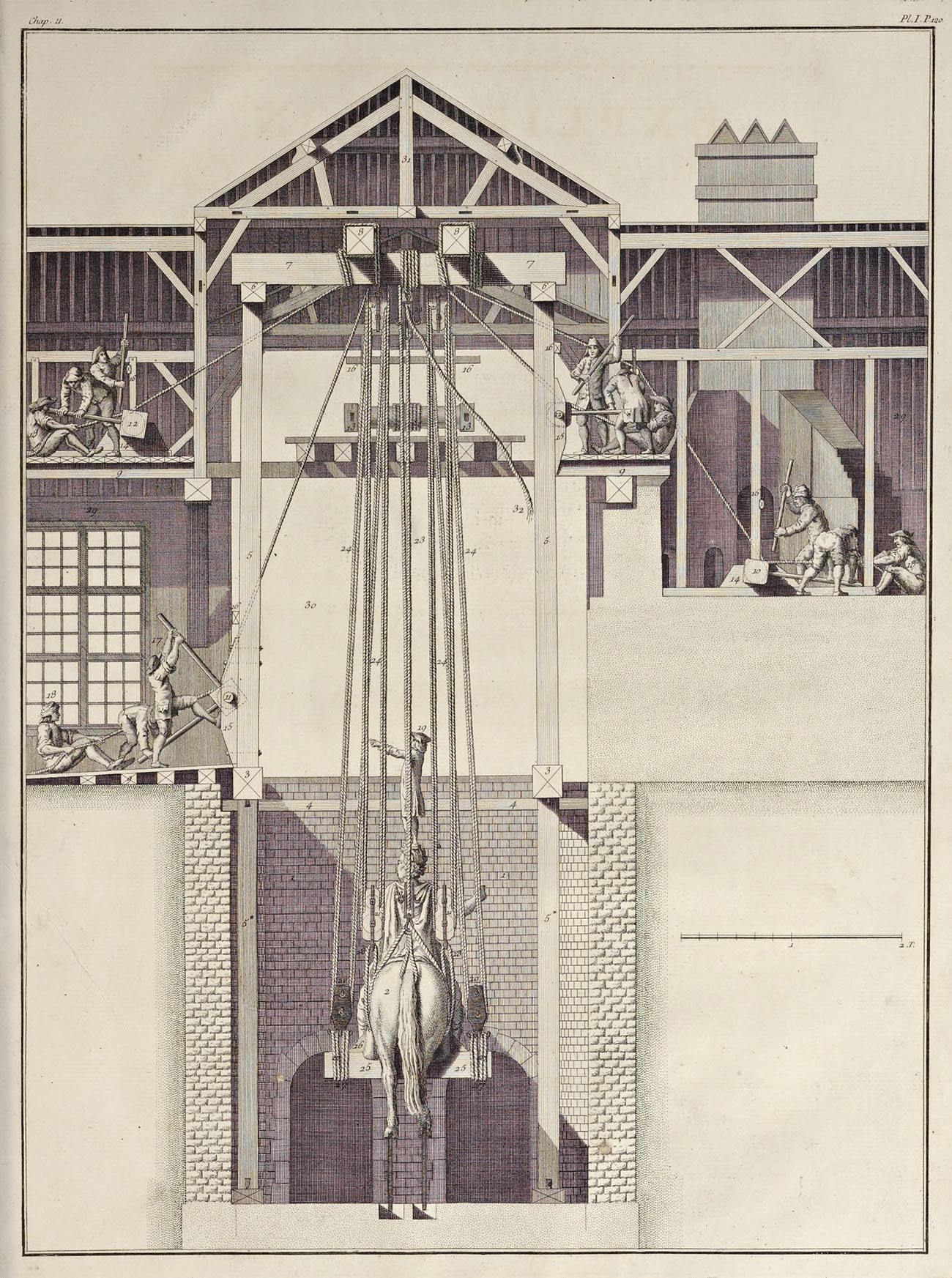

Equestrian Monument to Louis XV by Bouchardon, Benoît Louis Prevost, plate from Description des travaux qui ont précédé, accompagné et suivi la fonte […] de la statue équestre de Louis XV by Pierre Jean Mariette (Paris, 1768). Etching and engraving, folio format. The Getty Research Institute, 82-B2

Edme Bouchardon’s last masterpiece was one of the most prestigious and challenging commissions a sculptor could ever dream of: an equestrian monument. In 1748, the aldermen of Paris resolved to erect a statue in honor of King Louis XV in the Place Louis XV—the present-day Place de la Concorde—and entrusted Bouchardon to realize it. The resulting sculpture represented the king on horseback wearing a classical costume and crowned with laurel leaves. In his right hand, he held the baton of command, which rested on his thigh.

A painting in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum shows Place Louis XV from the viewpoint of the left bank of the Seine; Bouchardon’s monument, which was thirty-nine feet tall including the pedestal, stands in the middle of the grand space linking the Champs-Élysées, on the left, and the Tuileries Gardens, on the right.

A View of Place Louis XV and detail showing Bouchardon’s statue, about 1775–87, attributed to Alexandre Jean Noël. Oil on canvas, 19 5/8 x 29 1/2 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 57.PA.3. Digital images courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

The preparatory work for the statue took many years, and, in fact, occupied Bouchardon until his death in 1762. After producing a great number of drawings (255 studies for the horse and the rider are conserved at the Louvre!), Bouchardon completed the large-scale plaster mold in January 1757. The casting in bronze took place on May 5, 1758; however, a setback with the casting, coupled with Bouchardon’s meticulousness, delayed the completion of the sculpture for another five years while it was repaired and refined.

The statue was finally installed on a temporary pedestal in 1763, a few months after the artist’s death. Nine years later, the pedestal was completed with the addition of a bronze decoration of the four Virtues and two reliefs by sculptor Jean-Baptiste Pigalle.

Neck and Head of Bridled Horse, Front View, 1748–53, Edme Bouchardon. Red chalk, 21 1/8 x 16 1/8 in. Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts Graphiques, INV.24521. Image © Musée du Louvre, dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Suzanne Nagy

In addition to being an artistic endeavor for Bouchardon, the monument also represented an important technical challenge. Preparing for and supervising the pouring of thirty tons of metal, chiseling the seventeen-foot-tall statue, and installing it on the square was a spectacular tour de force! For this reason, a book was published to precisely record the casting of the statue by foundryman Pierre Gor after Bouchardon’s model, as well as the pulley system used to lift the artwork and transport it to the square. The volume’s introduction states its intent to “transmit to posterity, via engraved plates and accurate and instructive memoirs, the workings of all operations.”

Indeed, this treatise contains detailed, carefully labeled engravings that wonderfully illustrate the text, explaining each step of the process. I particularly like the image depicting the removal of the statue out of its pit, with the engineer in charge of the operation standing on top of the king’s head!

Removal of the Bouchardon Statue from the Foundry Pit, Pierre Patte, plate from Description des travaux qui ont précédé,accompagné et suivi la fonte […] de la statue équestre de Louis XV by Pierre Jean Mariette (Paris, 1768). Etching and engraving, folio format. The Getty Research Institute, 82-B2

The Getty Research Institute recently digitized the book, so you can virtually flip through it yourself here. If you are curious about the fascinating technical aspects of sculptural production, but are not fluent in French (fortunately for me, I am French!), you may enjoy a video created specifically for the exhibition Bouchardon: Royal Artist of the Enlightenment.

In the early stages of planning the exhibition, my colleague Jane Bassett, conservator at the J. Paul Getty Museum and a specialist in casting techniques, and I decided it was important to make the priceless contents of the book more broadly available. We were so impressed by the quality and beauty of the engravings that we decided to select the most significant ones and have them animated. In five minutes or so, the animations summarize six years of work, from the fabrication of the large-scale plaster mold to the installation of the bronze statue on the pedestal.

We tried to incorporate all the most compelling information contained in the book, such as the time required for each step and the materials used. Of course, we could not include everything, so I will share a couple of the foundryman’s tricks here. For instance, when the investment mold acquired a “cherry color,” founders knew that it had been properly heated and was ready to receive the molten bronze. In addition, when the surface of the metal in fusion became as clear as a mirror, it meant the material had achieved the right temperature for pouring.

You can see and enjoy the video in the exhibition; it is located next to the case displaying the book itself. If you cannot visit the Getty Center, the animation is also available on the museum’s YouTube channel here (and embedded below).

Sadly, Bouchardon’s equestrian statue remained standing on its pedestal for barely thirty years. Like almost all statues of royal likenesses, it was destroyed during the French Revolution, in the days following the insurrection of August 10, 1792. As the video shows, only the right hand of the king survives today, but that is a different story! Stay tuned, because another blog post dedicated exclusively to this fragment will appear soon. In the meantime, you have until April 2, 2017, to come admire the surviving bronze hand together with many Bouchardon masterpieces on loan from important museums around the world.

Installation view of Right Hand from the Equestrian Statue of Louis XV (1758); in the background is a mural enlarging one of the prints from the treatise, which shows workmen putting the statue on a chariot to be transported to Place Louis XV. Sculpture by Edme Bouchardon, courtesy Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo: Anne-Lise Desmas

Thank you. I took art history classes in college and plan to visit this exhibit on Friday, March 31. Your articles are outstanding. Thank you for making this information available be my visit.