Edme Bouchardon’s last masterpiece, a thirty-nine-feet tall Equestrian Monument to Louis XV, once stood in the middle of Place Louis XV—present-day Place de la Concorde—in Paris. Despite taking several years to create, an epic process that I detailed in a recent post, the bronze sculpture remained in place for less than three decades. Following the insurrection of August 10, 1792, Parisians toppled this emblem of royal power. Now, all that remains of the monument is the king’s right hand holding the upper part of the baton of command, which is currently on display in the final gallery of the Getty Museum exhibition Bouchardon: Royal Artist of the Enlightenment. How did this fragment survive the destruction of royal images and symbols during the French Revolution?

An anonymous drawing owned by the Louvre shows the crowd that gathered on Place Louis XV to witness the removal of the bronze statue. One man stands on top of the empty pedestal, still holding a stick he may have used as a lever, while two others are busy below trying to remove the relief that decorated the base. In the foreground, the horse and the king are upside down; the arms of the former and the head of the latter broke off when the sculpture fell and hit the ground.

Destruction of the Monument of Louis XV (at right, a detail of Bouchardon’s statue). Artist unknown (French, late 1700s). Pen and ink, 6 ¼ x 4 in. (15.8 x 10 cm). Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts graphiques, Paris

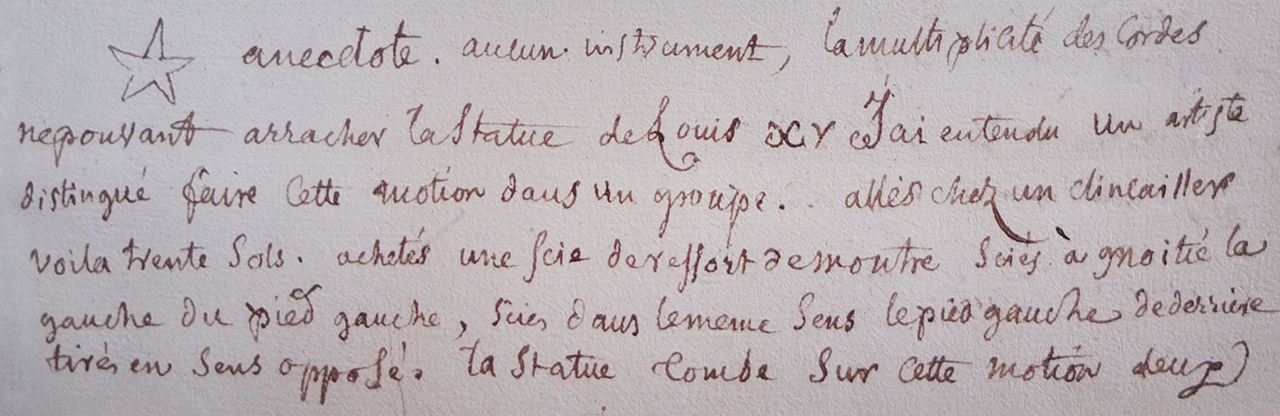

On the back of the drawing, an inscription provides even more information about the event, with a level of detail that indicates the anonymous artist attended the scene.

“Anecdote: Since, any instrument, and the multiplicity of the ropes were unable to pull out the statue of Louis XV, I heard a distinguished artist express this suggestion among a group. Go to an ironmonger’s. Here you are with 30 sols [a currency of the French Ancien Régime]. Buy a saw for clocks’ springs. Saw the left half of the left foot, saw in the same direction the rear left foot, pull in the opposite direction. The statue fell down in this way.”

Inscription (in French) on the back of the drawing illustrated above

It sounds like the Parisians had a hard time pulling down the statue! They had no idea it was so well anchored into the pedestal, all thanks to the tenons—projecting pieces of iron—that were saved from the original iron armature for this purpose. A video produced for the exhibition explains all the steps in the casting and installation of Bouchardon’s sculpture, and the 4 minute and 38 second mark illustrates this part of the process in particular. The print below shows the long length of the tenons; it is not surprising that the Parisians had to saw the legs of the horse to topple it!

After the statue was removed, the empty pedestal remained, and it was still up on the square when Louis XVI was executed on January 21, 1793. It appears in many images recording the king’s beheading.

Left: Installation of the Bouchardon Statue on Its Pedestal, Pierre Patte, plate from Description des travaux qui ont précédé, accompagné et suivi la fonte […] de la statue équestre de Louis XV by Pierre Jean Mariette (Paris, 1768). Etching and engraving, foglio format. The Getty Research Institute, 82-B2. Right: Execution of Louis XVI (showing the empty pedestal of the Statue of Louis XV at right), 1794, Isodore Stanislas Helman after Charles Monnet. Engraving. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France. Source: Wikimedia Commons

If you look closely at the left foreground of the drawing, you can distinguish the right forearm of the king holding the upper part of the baton of command. It broke off during the fall and is lying on the paving stones of the square.

Detail of the above-illustrated drawing of the Destruction of the Monument of Louis XV. Artist unknown (French, late 1700s). Pen and ink, 6 ¼ x 4 in. (15.8 x 10 cm). Musée du Louvre, Département des Arts graphiques, Paris

While the bronze elements of the monument were melted down, the Council of the Municipality of Paris decided to give the fragment of the hand to Jean Henri Latude, also known as Masers de Latude. He was famous for enduring long prison terms, including at the Bastille, and for his spectacular escape attempts. From 1749 to 1784, he was imprisoned for attempting to defraud the Marquise de Pompadour; Latude had offered advance information about a conspiracy to poison the marquise, an intrigue he had manufactured himself to extort a reward. In 1787, he told this story and others in his glamorized memoir, Le despotisme dévoilé, which enjoyed great popularity during the French Revolution.

Due to these circumstances, the hand quickly became famous. The writer and journalist Louis-Sébastien Mercier wrote about the gift to Latude in his Dernier tableau de Paris, a report of the French revolutionary events that many read just after its publication in London in September 1793. In Nouveau Paris, published in 1797, Mercier devoted an entire chapter to the episode, titling it “The Bronze Hand” with a touch of irony, as the original flesh-and-blood hand had signed Latude’s arrest warrants.

Latude continued to intrigue people, even after his death in 1805. In 1814, the author of the London gazette The Pamphleteer described meeting the former prisoner in December 1801:

“He was seventy six years old, strong and active for his age; he had before him on a table all of his tools and musical instruments and, in the midst of those, the hand of the bronze statue of Louis XV, which had been on the Place de la Concorde, and he explained them, and he told the story of his wonderful escape from the Bastille, in a spirited and interesting manner.”

On April 23, 1805, as part of the April 12th news from Paris, the political periodical L’Abeille du nord reported:

“Yesterday, the furnishings of the deceased Mr. de Latude were sold…Among these, there was the ladder, fabricated with the fabric of his shirt and fragments of a chair, with which he escaped out of the donjon where he was imprisoned. This ladder was exhibited at the Louvre in 1789, with the portrait of M. de Latude. The right hand of the statue of Louis XV, destroyed in 1793 [a mistake for 1792], was in his possession, and was sold for about 80 francs. The ladder, for which an English man, according to M. de Latude, had offered him an incredible sum of money, was sold for the same price.”

The fascinating story was even fictionalized by Victor Hugo, who incorporated the event into his 1874 novel Quatrevingt-treize (Ninety-Three) and attributed the decision to give the fragment to Latude to his protagonist, Cimourdain. Here is a passage from the book translated from French by Frank Lee Benedict the year it was published:

“Who could have prophesied to [Latude] that [his] prison [the Bastille] would fall—this statue would be destroyed? That he would emerge from the sepulcher and monarchy enter it? That he, the prisoner, would be the master of this hand of bronze which had signed his warrant; and that of this king of Mud there would remain only his brazen arm?”

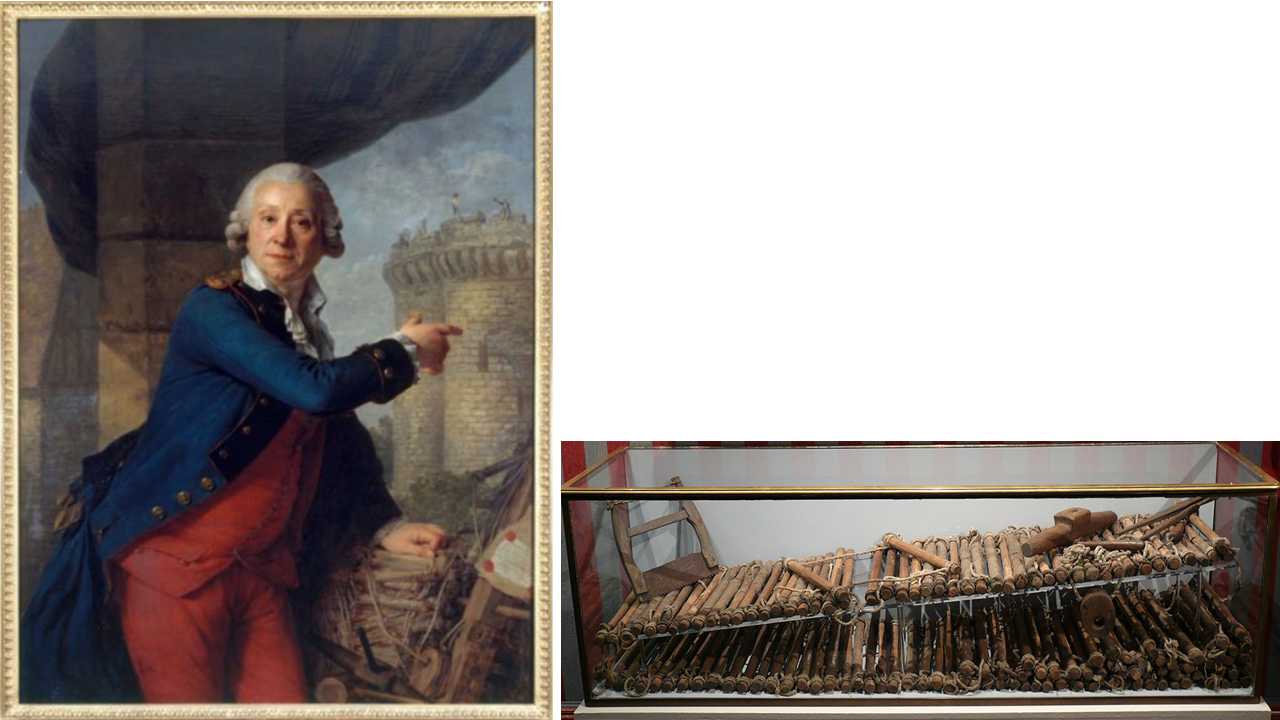

The Musée Carnavalet in Paris owns a portrait of Latude created in 1789 by the French painter Antoine Vestier. Latude rests one hand on his famous makeshift ladder, and the other points to the Bastille donjon. The ladder itself is also on display in the museum, along with the bronze hand!

Left: Portrait of Jean Henri Masers de Latude (1725–1805), Antoine Vestiers. Oil on canvas. Paris, Musée Carnavalet. Courtesy of Paris Musées Collections–Mairie de Paris. Right: Ladder used by Masers de Latude to escape from the Bastille. Paris, Musée Carnavalet. Image courtesy of rodama1789.blogspot.com

Thanks to other documents, particularly sales catalogues, it is possible to identify some of the other owners of the bronze hand during the nineteenth century and to reconstruct its provenance. A collector named Mr. Daval bought it at the sale mentioned in L’Abeille du nord in 1805. Then a curiosity dealer, Mademoiselle Delaunay, purchased the fragment at the sale organized after Mr. Daval’s death in 1822. She may have sold the hand quite fast, as it is not included in her going-out-of-business sales catalogue from 1827. We lose track of the fragment until 1860, when Mr. du Tronchay gave it to the Louvre. The Louvre now loans it to the Musée Carnavalet, since part of its collection focuses on the French Revolution in Paris.

Besides its captivating history, the bronze hand is also an interesting artistic fragment, showing the thickness of the bronze in the hollow palm and the extremity of the inner iron armature. These details correspond to the bronze-casting technique used to produce the statue, which is summarized in the aforementioned video. When the statue fell and broke apart, Parisians were surprised to discover it was hollow, and they made political pasquinades about it: “What? All of this was hollow? Yes, everything was hollow, power and statue!”

Installation view showing detail of the inside of Right Hand from the Equestrian Statue of Louis XV (1758) by Edme Bouchardon. Sculpture courtesy Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo: Anne-Lise Desmas

Last but not least, the high quality of this piece of bronze is surprising. The placement of the fingers on the baton of command and their position relative to one another are very natural, and the skin folds between the thumb and index finger and those at the end of the palm by the little finger are quite realistic. This artistry and realism is incredible given that the hand originally stood thirty feet above the ground! Although Bouchardon’s last monument did not survive intact, the king’s hand is a testament to his skill, and it became a masterpiece in and of itself.

Installation views showing close-up views of Right Hand from the Equestrian Statue of Louis XV (1758) by Edme Bouchardon. Sculpture courtesy Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photos: Anne-Lise Desmas

Comments on this post are now closed.