Frederick Hammersley in 2003 outside his home in Albuquerque, New Mexico, which now houses the Frederick Hammersley Foundation. Photography: Paul O’Connor. Courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA

The Frederick Hammersley Foundation recently donated the artist’s archives to the Getty Research Institute, as we shared last week.

Frederick Hammersley (1919–2009) first came to prominence as part of the group of Los Angeles artists who exhibited as “Four Abstract Classicists” (1959) and whose style came to be known as West Coast Hard-Edge.

Throughout his long career, Hammersley kept meticulous records about his work process and materials. It is rare and remarkable for an artist to record his creative process in as much detail and over such a prolonged period of time as Hammersley did. The depth of information contained in his archive is an incredible resource for art historians, for those charged with the display and conservation of his artworks, as well as for conservation scientists—such as Alan Phenix of the Getty Conservation Institute.

Alan Phenix prepares the scanning electron microscope for the examination of a paint sample. Photo: Scott S. Warren

Alan is a member of the project team for the Conservation Institute’s scientific research project Art in L.A., which is studying the materials and fabrication processes used by Los Angeles-based artists since the 1950s, as well as the implications these materials and process have for conservation. Frederick Hammersley is among the artists included in this project.

Frederick Hammersley’s paints and studio tools as left on his painting table at his home studio in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

At the Conservation Insitute, Alan focuses on analyzing the chemical composition and buildup of paints in works of art to reveal evidence of an artist’s creative process, choice of materials, and how the materials may have altered over time. His research helps conservators determine the best course of treatment.

In 2010 Alan, along with colleagues from the Research Institute, visited the Hammersley Foundation in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and had the opportunity to view some of the artist’s paints and tools. When Alan talked to me about this visit, his excitement at seeing these materials for the first time was contagious. Of special interest to him has been a four-volume notebook series, which Hammersley referred to as his “Painting Books.” These books contain copious notes on paintings, detailing Hammersley’s creative process from 1959 to within a few months of his death in 2009.

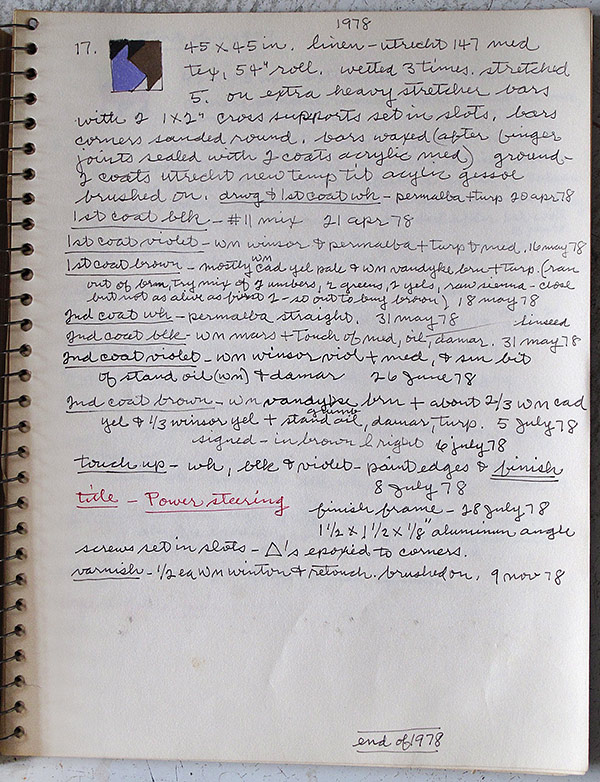

Painting Book 3 showing the entry for Hammersley’s painting Power steering, #17, 1978, in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Painting Book © Frederick Hammersley Foundation

The level of detail with which Hammersley documented his work is demonstrated in an entry from Painting Book 3 on the work Power steering, #17, now in the National Gallery of Art. Hammersley includes specific information on the types of tube paints used for the first and second coats (even noting he had run out of a particular paint color and had to go out to buy more), the varnish used, plus information about the frame, down to the detail of how the corner joints were reinforced.

“Normally, we obtain only minute samples of paint to analyze, so Hammersley’s Painting Books offer the unparalleled opportunity of a coherent and complete body of information compiled by the artist himself,” Alan told me. “His records allow for a level of understanding about materials, process, and conservation issues we simply can’t get through paint analysis alone.”

The Painting Books are now being transcribed, with the aim of eventually entering the contents into a text-searchable database. This information, together with the other archival materials now at the Research Institute, will serve as important research tools for detailed analysis of the painter’s practice, as well as a key reference for conservators who encounter Hammersley’s work.

Admiring the time and energy you put into your website and in depth information you offer.

It’s great to come across a blog every once in a while that isn’t the same unwanted rehashed material.

Great read! I’ve bookmarked your site and I’m adding your RSS feeds to my Google account.