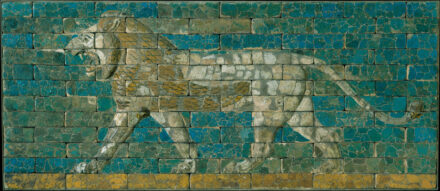

Triumphs of Myrrha and Daphne, late 1600s, Johannes Teyler after Giovanni Battista Lenardi. Etching colored à la poupée. The Getty Research Institute, 2015.PR.45

In early modern Europe, sugar was so rare and expensive that it gave rise to its own luxury art form: the sugar sculpture.

Magnificent statues of gilt sugar pastry, known as trionfi (“triumphs”), adorned banquets to show off hosts’ power and status. They often stood several feet tall, towering over guests. Prints, rare books, and a sugar tableau in the exhibition The Edible Monument: The Art of Food for Festivals reveal the story of this art form.

Just added to the exhibition is a newly acquired etching that offers a rare color vision of one of the greatest sugar sculptures in history. It depicts Myrrha and Daphne, two figures from a group of sculptures designed by Giovanni Battista Lenardi as table decorations for a banquet held for Pope Innocent XI on January 14, 1687. The print is a very early example of a color print published by Johannes Teyler, who invented a technique for printing engravings and etchings in multiple colors by applying two or more inks to one plate.

Installing the new acquisition (at left on wall) in The Edible Monument

The astonishing banquet that this print memorializes was organized by Roger Palmer, Earl of Castlemaine and ambassador to English king James II. Held at the Palazzo Pamphili in Rome, the dinner included 86 cardinals on the guest list. Atop a nearly 100-foot-long banquet table sat a vast sugarscape with a female figure symbolizing the Roman Catholic Church, and a winged warrior representing James II chasing away Fraud and Discord with his spear. Below the warrior lay a decapitated hydra representing the recent Protestant rebellion in England, which James had successfully crushed. Also included were mythological figures from Ovid’s Metamorphoses and smaller statuettes of lions, eagles, and unicorns.

Through these symbolic sugar sculptures, Palmer sought to remind the pope of the British king’s many religious victories for the Catholic Church. In return for such loyalty, he was asking the pope to fulfill Britain’s demands, such as appointing James’s royal advisor to the bishopry.

The etching depicts two figures from the group, Myrrha and Daphne. On the left, Myrrha is changed into a myrrh tree that splits open to release the infant Adonis. On the right, Daphne is changed into a laurel tree by her father, Peneus, to escape the pursuing Apollo, while Cupid flies nearby.

The etching hints at the splendor of the original sugar, which would likely have been brightly colored with various dyes. An earlier, non-colored etching of the same sculptures (shown below) is also part of the Getty Research Institute’s collections.

Triumphs of Myrrha and Daphne, Giovanni Battista Lenardi, draftsman; Arnold van Westerhout, engraver. Engraving in John Michael Wright, Raggvaglio della solenne comparsa (Rome: Domenico Antonio Ercole, 1687). The Getty Research Institute, 83-B3076 c.1

As it happened, this was one of the last great hurrahs of sugar-as-propaganda. As the supply of sugar increased, its price fell, and its appeal as a status symbol slowly melted away.

See all posts in this series »

Dear Madam, Dear Sir,

I am the compiler of the NHD – Hollstein volumes on Johannes Teyler: http://www.hollstein.com/johannes-teyler.html. Some amendments to your text:

“The print is a very early example of color printing by Dutch etcher Johannes Teyler, who invented one of the first techniques for color printing by applying ink to copperplate.”

Johannes Teyler was not the ‘etcher’ of the plate. Teyler may have been the (re)inventor of the process – it was already known in the early 16th century, though in a more primitive form – of inking one intaglio plate with two or more different colours of ink. He organised and financed a workshop specialised in colour printing fabric in Holland in the 1680s. He was not an artist, printmaker or plate printer – by profession he was a military engineer. Others etched, engraved and printed the plates for him. The prints on paper produced in his workshop were never traded at the time. Only after the dissolution of the workshop in 1697 the colour prints came on the market. Typically none of them has an address.

The sentence “who invented one of the first techniques for color printing by applying ink to copperplate” should better read: “who invented a technique for printing engravings and etchings in multiple colours by applying two or more coloured inks to one plate”.

For more information about the process and its history see: Ad Stijnman, Engraving and Etching 1400-2000 (etc.), London 2012, pp. 341-352.

With best wishes,

Ad Stijnman.

Dear Ad, Thank you so much for taking the time to comment and to lend your expertise. We will amend the post as you suggest. —Annelisa, Iris editor