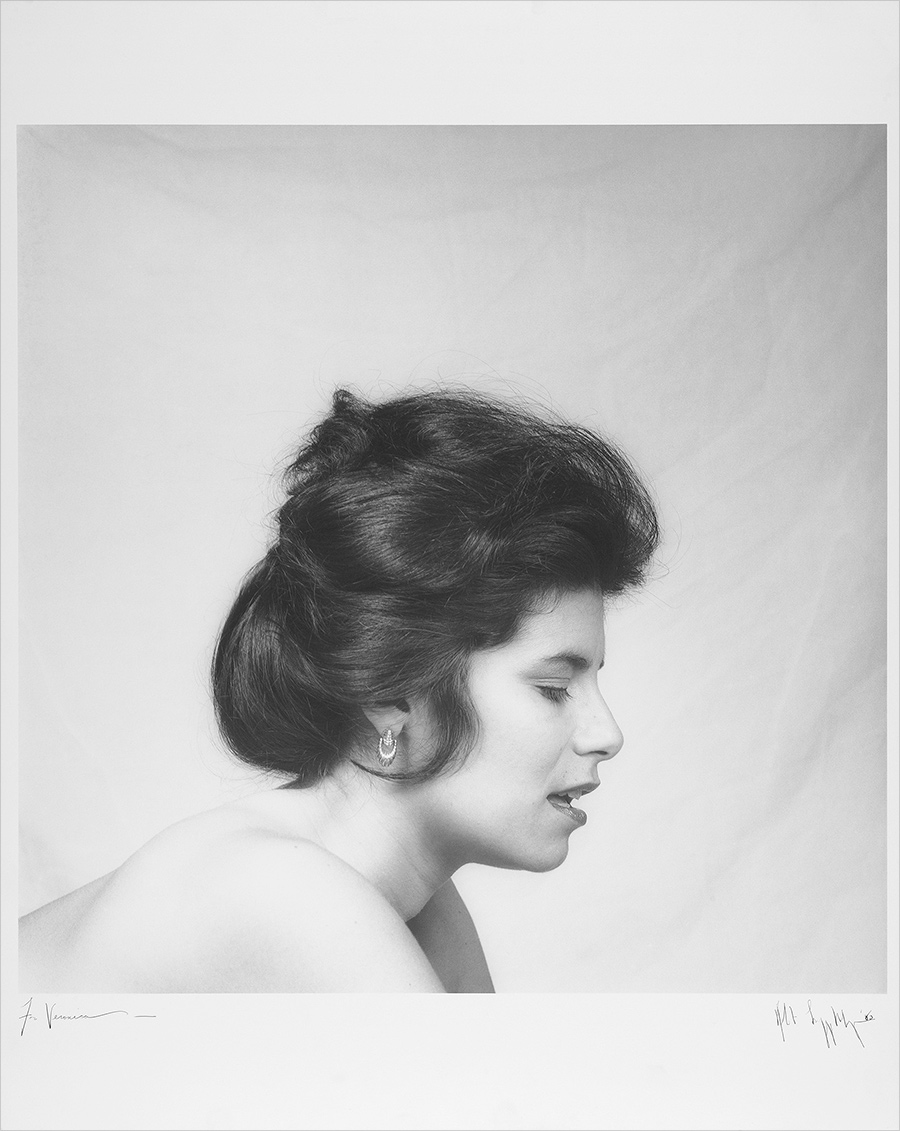

Veronica Vera, 1982, Robert Mapplethorpe. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. All rights reserved

At the opening for the Getty Museum exhibition Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium, I was thrilled to see Veronica Vera among the crowd. Composed and elegant, she warmly responded to my introduction and we agreed to meet in New York later that month.

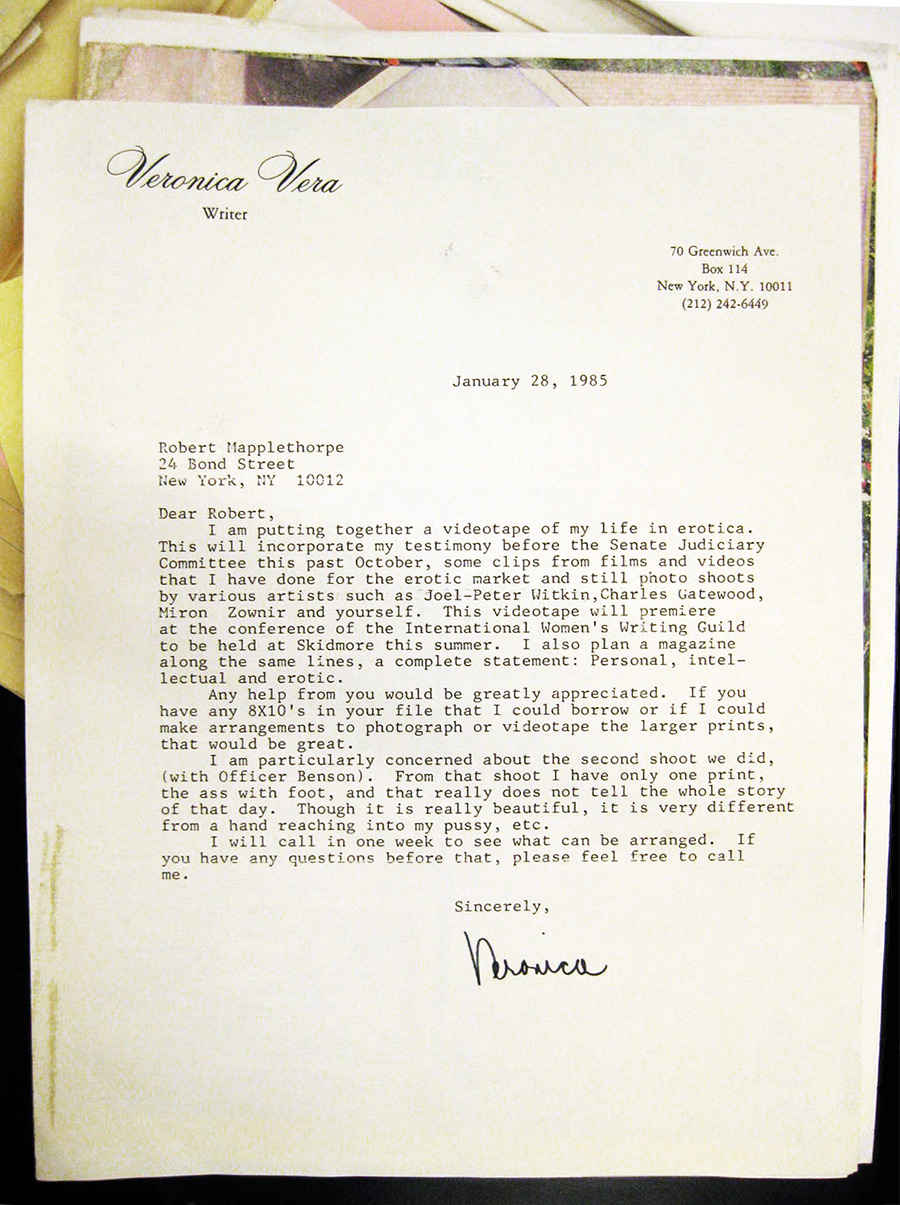

It was Mapplethorpe’s 1982 photographs of Vera that made me vividly aware of her. As intriguing as these are, however, it was a letter sent by Vera to Mapplethorpe that captured my curiosity about this extraordinary woman. Her letter was one of the first items I photographed during my research in the Mapplethorpe archive at the Getty Research Institute.

Residing among hundreds of letters sent to Mapplethorpe from the early 1970s until his death in 1989, Vera’s letter, dated January 28, 1985, asks Mapplethorpe for permission to use one of his portraits of her to illustrate a video. Along with clips from her work in erotic films and portraits by artists, she explains, “this

will incorporate my testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee this past October.”

Letter from Veronica Vera to Robert Mapplethorpe dated January 28, 1985, from the Robert Mapplethorpe archive. The letter begins, “I am putting together a videotape of my life in erotica…” The Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.20. Gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Reproduced with the permission of Veronica Vera

I later read that Vera had testified as a proponent for freedom of sexual expression during an investigation concerning pornography (Rich Moreland, Pornography Feminism: As Powerful as She Wants to Be, page 28). That committee, organized in 1984, concluded with the recommendation of no additional censorship laws. Yet, just a few months later, the Meese Commission was formed by then–Attorney General Edwin Meese and politicians bent on reining in the sexual liberties achieved in the preceding decades. Very soon after, these same forces held Mapplethorpe’s own work in contempt.

A Google search led me to Veronica’s blog, which highlights her work as an author, artist, advocate, and activist, and as the founder and dean of “the world’s first transgender academy,” Miss Vera’s Finishing School for Boys Who Want to be Girls. Lighthearted in name and loving in its approach, the school has been a catalyst, a healing and learning center for thousands of students.

To complement her teaching of poise and grace, which Vera possesses in abundance, she has written several books, including the recently published Miss Vera’s Cross Gender Fun for All. When we met in New York, I had the pleasure of visiting the school with Frances Terpak, curator at the Research Institute and co-author with me on the book Robert Mapplethorpe: The Archive. There Vera showed us the school’s library, inspiring Frances to request several titles, including Vera’s own books, for the Getty’s Research Library.

Veronica Vera (left) and me (right) at the entrance to Miss Vera’s Finishing School for Boys Who Want to be Girls in New York City

When I approached Vera at the Getty opening, she was being photographed in front of a portrait of Thomas Williams, another of Mapplethorpe’s pioneering collaborators. I asked about Williams’s significance for her, and she revealed that she and Williams had become lovers some years after Mapplethorpe’s death. Vera suggested I look at a new post on her blog that narrates a fuller story. Inspired by the unexpected reemergence of the lost portrait by Mapplethorpe shown at the top of this post, the post portrays a sexually vibrant culture in New York during the early 1980s that was forging a new sexual liberation even as it confronted the devastation of the AIDS epidemic.

As his archive attests, Mapplethorpe identified with this culture, a culture he strove to make known. Consciously assembled and curated by the artist himself, the Mapplethorpe archive represents an important resource of ephemera and primary materials about freedom during a period of turbulent sexual politics in American history.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.