Hearsay of the Soul, a video installation by Werner Herzog, lingers with you long after you’ve seen it. In an effort to investigate what makes the work so affecting, we invited a diverse group of experts to articulate how they experienced this multifaceted work, and how they understand it.

Following our talk with independent curator Paul Young, we turned to Getty Museum curator of paintings Anne Woollett, who reflects on Herzog and the Dutch artistic tradition.

Curator Anne Woolett, photographed inside Werner Herzog’s installation Hearsay of the Soul

What struck you most about Hearsay of the Soul?

The prints by Hercules Segers, which I was already familiar with, took on a really transfixing quality. The fact that Herzog made them mobile creates a very meditative experience.

How does Hearsay of the Soul transform these 17th-century landscape etchings by Hercules Segers?

Segers’s etchings are relatively small in scale; they’re very detailed and their textures and compositions draw you in. Projected on a large scale and with movement added, Herzog gives them a sense of emotional intensity.

In Segers’s time, was “landscape” a common subject in art?

There’s a rich tradition of landscape painting and graphic work in the Netherlands. Segers encapsulated the work of 16th-century Flemish artists like Pieter Brueghel the Elder, who portrayed towering rocks that seem to capture the spirit and grandeur of an ancient past, combined with the flat landscape that is the reality of the Netherlands.

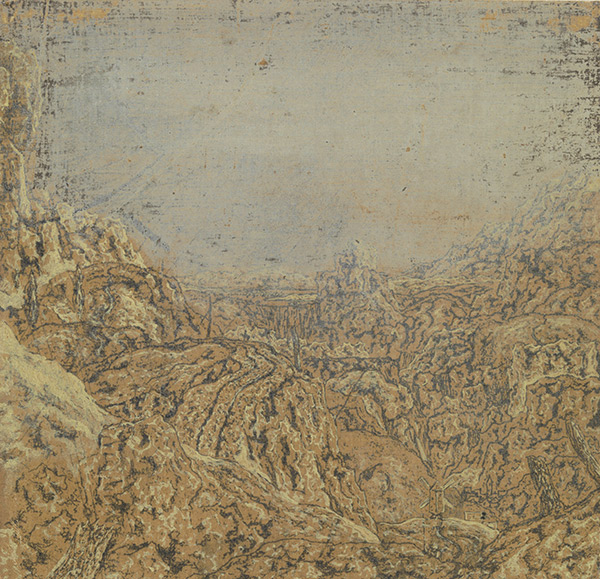

Segers created fantasy landscapes that reflect all of the mythology in this landscape tradition. And he pushed his ideas further through his innovative technique. He printed on colored papers and used different colored inks to bring a sense of foreboding to desolate, rocky places. They’re places that we want to explore and become lost in, and that’s the magic of his images.

Mountain Gorge Bordered by a Road, about 1615–30, Hercules Segers. Etching with oil paint, 15.4 × 16 cm. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; on loan from the Rijksacademie van Beeldende Kunsten

Did Segers ever travel to the kind of mountainous terrain we see in his art?

In the early 17th century you have artists who worked from experience, like Roelandt Savery, who made sketching trips in the mountains around Prague and in the Tyrol. A spectacular alpine landscape by Savery—with a waterfall and towering rocks—is in the Museum’s collection.

Landscape with the Temptation of Saint Anthony, 1617, Roelandt Savery. Oil on panel, 19 5/16 x 37 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2008.73

Segers, as far as we know, did not make such trips, but would certainly have been familiar with prints by Brueghel the Elder. And Brueghel, of course, made a trip to Italy, and his ideas of the mountainous landscape come from his experience of crossing the Alps.

Who would have been interested in Segers’s imagined scenes and why?

Segers’s innovations and interest in making the print medium a diverse art form—where cropping, different inks, coloring, and other techniques could make individual impressions independent works—was very timely. His images resemble nothing else at that moment. So a collector interested in creative artistic process and a unique piece would have been interested in Segers’s work.

The imagined landscape is a real skill, and Rembrandt was absolutely captivated by Segers. Rembrandt owned eight paintings by him. He actually modified a work by Segers, putting his own stamp on it—a great mark of respect.

A Wooded Road, about 1650, Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn. Pen and brown ink and brown wash on paper toned with brown wash, intentionally scratched by the artist, 6 1/4 x 7 15/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.GA.95

Today Segers is not well known. Did he influence other Dutch artists?

Segers’s independent artistic personality was an inspiration in his time, and also through the 19th century, when there was a revival of interest in landscape and its relationship to larger concerns such as the divine and the mythological. Printing plates without wiping them down completely, for example, or using plates with a previous image on it, produced quite unusual pieces. Although his techniques were not specifically imitated, his approach was to produce works that were very individual.

His representation of imagined scenes inspired artists like Philips Koninck, a great painter of landscapes. Koninck continued the bird’s-eye perspective that allows the viewer to float above and gaze far into the distance, as you can see in a painting in the Museum’s collection.

A Panoramic Landscape, 1665, Philips Koninck. Oil on canvas, 54 1/2 x 65 1/2 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.PA.32

It’s a very old-fashioned approach that enabled artists to create landscapes of monumentality and power.

What does “the divine” mean in relation to landscape traditions in art?

The concept of the divine in landscape is very interesting, but complex. A devout viewer about 1600 might have described landscape as evidence of divine creativity. There was the sense of God’s presence in nature, its awesome forces and its forms such as mountains; also the sense that the vastness of landscape puts humans into perspective. So we see in some of Segers’s work tiny figures or small buildings, details that take us into the landscape and invite us to explore it—to consider man’s true place in nature, and in the cosmic order.

____

Next in Four Minds on Herzog: musicologist Nancy Perloff on February 5, and video art curator Glenn Phillips on February 12. See the interview with independent curator Paul Young here.

Comments on this post are now closed.