From multi-hued strikethrough to total erasure by knife, medieval copyediting was a lot more colorful than today’s “track changes”

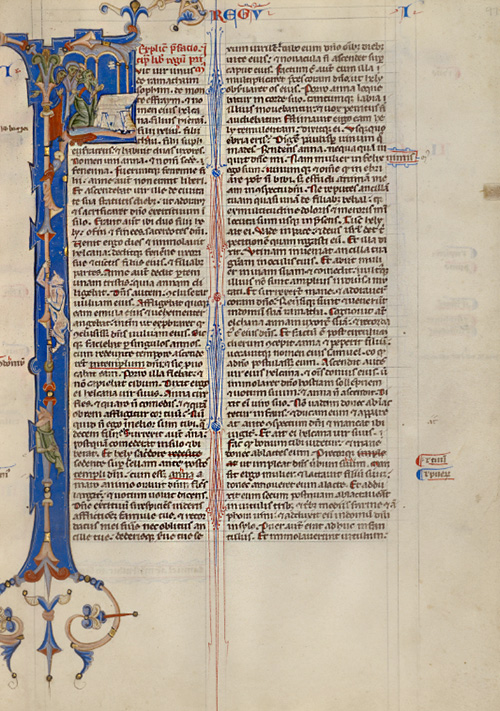

Detail from a Decorated Canceled Page in the Abbey Bible, about 1250–62. Ms. 107, fol. 96v

The age-old (read: “medieval”) practice of striking through text to indicate a corrected error has been dealt a blow. The new editor of Gawker, the blog that turns today’s gossip into tomorrow’s news—as the site’s aphoristic catchphrase proclaims—has dropped the strikethrough in favor of a hyperlink to the corrected text.

Last week, Craig Silverman of Poynter ran the story, offering a historical parallel in the form of a red strikethrough from an 11th-century Domesday Book. This was forwarded to me by colleagues asking if the Getty Museum’s manuscripts collection contains examples of medieval copyediting.

Medieval copyedits? We’ve got plenty—and there’s a lot more to them than the simple strikethrough.

An Elegant Strikethrough

At some point in the mid-13th century, a scribe realized he’d made a major mistake. In copying the opening chapter of one book of the Bible, he had omitted no less than 18 verses and jumbled the words of others. The scribe cancelled all of the text leading up to, and just following, the omission with beautifully painted parallel blue and red lines and began again on the facing page.

In the images below, which represent facing pages in the Abbey Bible, the two large letter Fs begin the Latin text Fuit vir unus de Ramathaimsophim (“There was a man of Ramthaimsophim…”). The text on both pages is the same (with various medieval abbreviations here and there) all the way up to the horizontal blue-and-red strikethroughs in the middle of the first column of the left-hand page. This is where things went wrong and the scribe lost his place.

Decorated Canceled Page in the Abbey Bible, Italian (probably Bologna), about 1250–62. Tempera and gold leaf on parchment, 10 9/16 x 7 3/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 107, fol. 86v

Initial F: Elkanah with Hannah and Peninnah in the Temple in the Abbey Bible, Italian (probably Bologna), about 1250–62. Tempera and gold leaf on parchment, 10 9/16 x 7 3/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 107, fol. 97

Starting Over

One tool in the medieval scribe’s arsenal of writing implements was a knife, which could be used to lightly scrape the parchment to remove erroneous text, spelling errors, or drawn elements. The portrait of Mark the Evangelist from the Helmarshausen Gospel below shows the writer inking a quill with his right hand and directing a knife at the parchment with his left. So far, he hasn’t made a mistake in copying any of the text, which the medieval reader would have seen mirrored on the facing page, but it’s always good to be prepared—copying can be an arduous and eye-crossing task, especially in medieval lighting conditions.

Saint Mark in a Gospel Book, German, Helmarshausen, about 1120–30. Tempera colors, gold leaf, silver leaf, and ink on parchment, 9 x 6 ½ in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig II 3, fol. 51v

Adding Skipped Text, Without Starting Over

Aimo and Vermondo Holding up the Church of Saint Victor in Legend of the Venerable Men Aimo and Vermondo, about 1400, attributed to Anovelo da Imbonante. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 10 1/16 x 7 ¼ in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 26, fol. 4v

If a scribe did make a mistake and didn’t want to start over or scrape the page clean, there were various ways of adding skipped text to the margins using a caret-like (^) symbol. Above, you can see that several Latin words from the legend of Milanese brother-saints Aimo and Vermondo were omitted—et inde spiritalia benefitia reportantes (“and thus spiritual benefit from receiving”)—and placed at the bottom of the page using a cross in the main text to call out the missing text. The missing words refer to the spiritual benefit that came from smelling the fragrant floral scents emanating from the brothers’ tomb when devotees prayed to the saints in the Church of Saint Victor in Meda, Italy.

Medieval “Whiteout”

Before whiteout, if you really wanted to blot something out of the text you could simply cover it entirely with gold (that is, if you were wealthy enough). That’s what happened in this copy of the Book of the Deeds of Alexander the Great. A later owner appears to have covered the text of the ex libris (from the library of) that most likely opened the manuscript with gold, seen beneath the miniature. He also had the coat of arms scraped away and colorful floral motifs added to blend the lower border together.

Vasco da Lucena Giving his Work to Charles the Bold in the Book of the Deeds of Alexander the Great, French and Flemish, Lille and Bruges, about 1470–75. Tempera colors, gold leaf, gold paint, and ink on parchment, 17 x 13 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 8, fol. 2v

Extreme Erasure

If you really want to see medieval editing in action, head to The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens before June 22 to see Lost and Found: The Secrets of Archimedes, which concerns a 10th-century manuscript originally containing texts by Archimedes, who lived in the 3rd century B.C. The pages were scraped and repurposed three centuries later as a prayer book, thereby becoming a palimpsest, a manuscript on which the original writing is effaced to make room for a new text.

The theme of repurposing and modifying manuscripts was also explored in a recent Getty Museum exhibition Untold Stories: Collecting and Transforming Medieval Manuscripts, and the exhibition webpage allows you to explore other example of medieval and post-medieval editing of manuscripts (but don’t look for these editorial practices on Gawker any more).

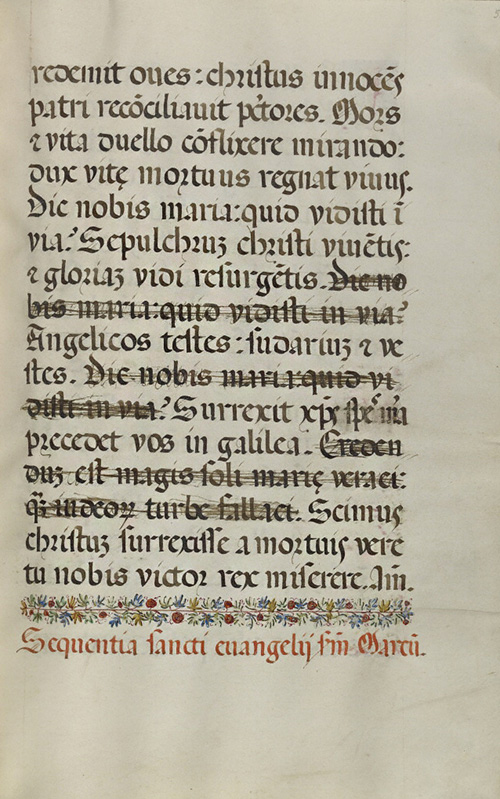

I’ll leave you with one last example of medieval copyediting: a heavily edited text page from a Missal. The lines for Easter Sunday mass, asking the Virgin Mary what she saw along the road as Christ went to the cross have been entirely, and not very precisely, struck out.

Decorated Text Page in the Missal of Bishop Antonio Scarampi, 1567, Fra Vencentius a Fundis. Tempera and gold leaf on parchment, 16 1/8 x 10 5/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig V 7, fol. 58

Fascinating article. I knew about knife scraping method to remove errors but not the other ones. Scribes were endlessly creative.