Each October we become accustomed to seeing skeletons in unexpected places: on neighbors’ lawns, in the seasonal aisle of the pharmacy, peering out from costume shop windows. In the 19th century, skeletons found their way into people’s homes not only in celebration of Halloween or Día de los Muertos, but as a form of entertainment.

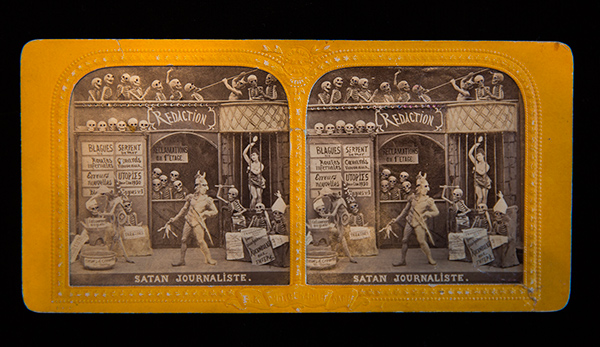

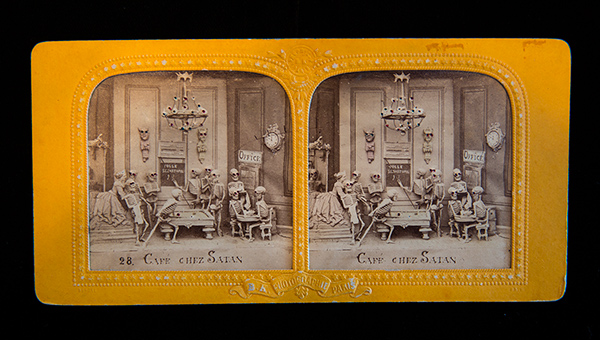

The Getty Museum’s collection includes a few images from a large group of photographs featuring claymation-like skeletons carousing in hell. Published in France in the 1860s and ‘70s, the photographs appear at first glance to be 19th-century precursors to the animated skeleton army of the 1963 movie Jason and the Argonauts, with a madcap flair.

Satanic Adventures

The skeletons’ eyes glow when seen against the light. In this one, even the chandelier lights up!

Known by collectors as “diableries,” or devil views, these photographs of frolicking skeletons were produced as stereographs. Two images are affixed side by side and viewed with a special piece of equipment that allows your eyes to bring the separate images into a 3D experience. It’s a little like watching Avatar with 3D glasses or looking through an old View-Master.

Because color photography wasn’t yet invented in the 1860s, these diableries were printed on thin paper, and color was added to the backs of the photographs by hand. When held to the light, the images suddenly come alive in riotous hues streaming through strategically placed pinpricks. Even 150 years later the effect is captivating, if comically lo-fi.

Admiring a diablerie in the Photographs Study Room

The lurid colors of the diableries also draw attention to the details of scenes as captivating as the minutiae of a dollhouse drama. Skeletons cavort in the boudoir of Madame Satan, visit a library in which books are replaced by skulls (La Bibliotheque Infernale), stage a raucous symphony (Concert Infernal), hold a lottery (rigged, of course, so that Satan wins), play pool, and—in my favorite image, sadly not in the Getty collection—ice skate. Hell has frozen over!

And Satan? He idly fishes, holds court with skeletons and sorcerers, throws a wild party, rigs the stock market, models for a photographic portrait, holds late-night feasts, and races in a bicycle sprint.

Take That, Napoléon III

Playfully staged, the series seems purely humorous—until you learn when and why they were made. These skeletons’ rowdy antics were a clever form of political satire. A fascinating recent book by Brian May, Denis Pellerin, and Paula Fleming explains that Satan is in fact a stand-in for Emperor Napoléon III of France, who instituted restrictive policies while spending lavishly on amusements for friends and family.

If you’re interested in the fascinating visual culture of the 19th century, or in photography as popular entertainment and social commentary, it’s well worth flipping through their book Diableries: Stereoscopic Adventures in Hell. For many years the diableries could be discovered only through specialist periodicals or the anecdotes of photography collectors, so it’s great to see the photographs from various series gathered together in one generous publication. Best of all, Diableries includes a stereoviewer to enable readers to experience the skeletons as they were intended to be seen, in three dimensions. The book also includes instructions on making stereographic images at home, which is quite easy to do with a digital camera and printer.

As the book makes clear, the diableries’ humor is all the more impressive given the strict censorship in France of the 1860s and ‘70s, when all imagery was subject to government review. It’s fun to flip through and chuckle at the resourcefulness of 19th-century publishers, who knew as well as today’s television producers how to blend comedy and politics into a satire no less sharp for its impish guise.

The hand coloring of the diableries series is quite a trick, but the resulting experience is certainly a treat.

_______

The Museum is in the process of digitizing these and other stereographs in the collection, and making them available on our website.

Comments on this post are now closed.