On September 27, 2016, the Getty Research Institute’s exhibition World War I: War of Images, Images of War opened at the Musée Würth France Erstein in the Alsatian village of Erstein, where it will be on view until January 8, 2017. This is the third venue for this exhibition, which was inaugurated at the Research Institute in November 2014 for the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War. In 2015 the show, which had a record attendance of more than 160,000 visitors while on view in Los Angeles, traveled to the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum in St. Louis.

At the Musée Würth France Erstein, the exhibition is being presented for the first time not only to a European audience, but also, and quite importantly, within the political and cultural context of Alsace—a region of great significance during the First World War and, more generally, in the history of the tense, difficult relationship between France and Germany.

A Fraught History

For most of history, Alsace, located on the west bank of the Rhine River, belonged to the German-speaking area of central Europe. During the seventeenth century, King Louis XIV claimed that the region was situated within the “natural borders” of France and annexed it. For the next 200 years, the area was alternately claimed by both nations. Alsace therefore has a unique national identity composed of cultural, architectural, and linguistic influences from both Germany and France, and it maintains a number of idiosyncrasies and systematic differences.

The modern history of Alsace and the neighboring region of Lorraine was largely driven by the strong nationalist rivalry between France and Germany and each country’s push for expansion, enacted on both sides at the expense of the local population and its sense of identity. The competition ultimately led to the Franco-German War of 1870 to 1871.

Germany defeated France in a rather swift victory and immediately announced the annexation of Alsace and Lorraine. This step was accompanied by measures imposed on the Alsatian population in an attempt to reduce the cultural, linguistic, and social influence of France throughout the area. Residents were forced to either change their nationality to German or leave their homes and move further west behind the newly established boundaries of France. In addition, German became the mandatory language in school.

Modern Warfare

During the First World War, the region endured heavy fighting and significant casualties, as well as considerable damage to monuments. Up to 30,000 soldiers lost their lives in the strategic Battle of Hartmannswillerkopf alone.

In the minds of the French, Alsace and Lorraine had become a symbol for the humiliating defeat suffered less than 40 years earlier—so military leaders were eager to recover the region. Upon the mutual declarations of war by Germany and France in 1914, both countries attacked the population of the respective “other” in their countries.

In France, German citizens were arrested and interned, while in Alsace and Lorraine, the Germans’ fear of French uprisings motivated further laws and restrictions, including a ban of the French language in public under threat of penalty and the installment of official names and titles in German. Registrars usually rejected French Christian names for children, and strict censorship of anti-German sentiment was implemented.

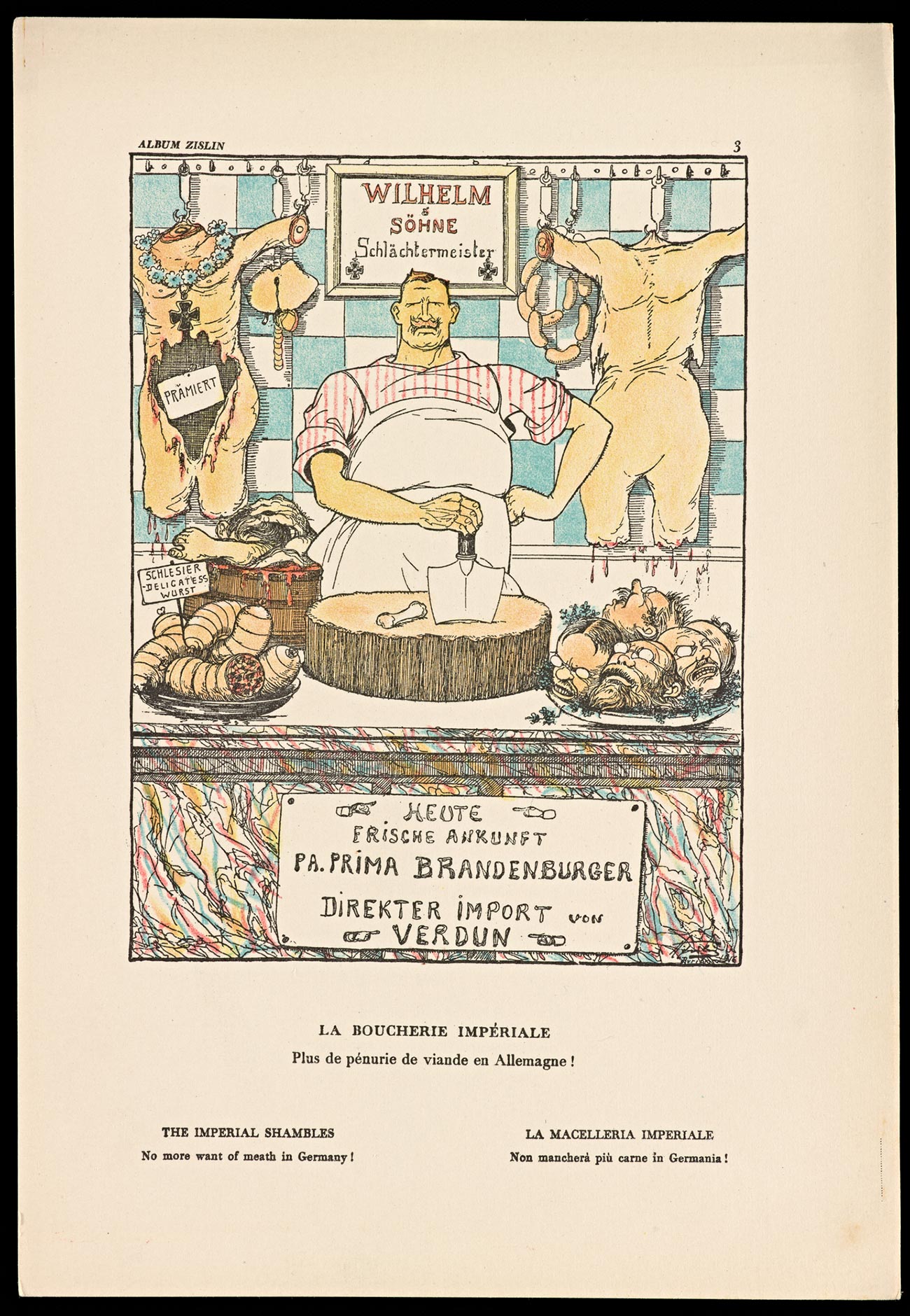

While the history and fate of the area became an important tool in the propaganda of both countries, the lack of acknowledgement of a specific regional identity of Alsace, and the feeling of being forcefully subsumed by an external government and culture, also fueled local propaganda production against the German occupation. Several examples, such as artworks by the famous Alsatian illustrator Henri Zislin, are part of the Getty Research Institute exhibition.

La Boucherie Impériale, Henri Zislin. Printed monograph in L’Album Zislin: Dessins de Guerre (Paris: Berger-Levrault, 1916). The Getty Research Institute, 1551-043

An Uneasy Reality

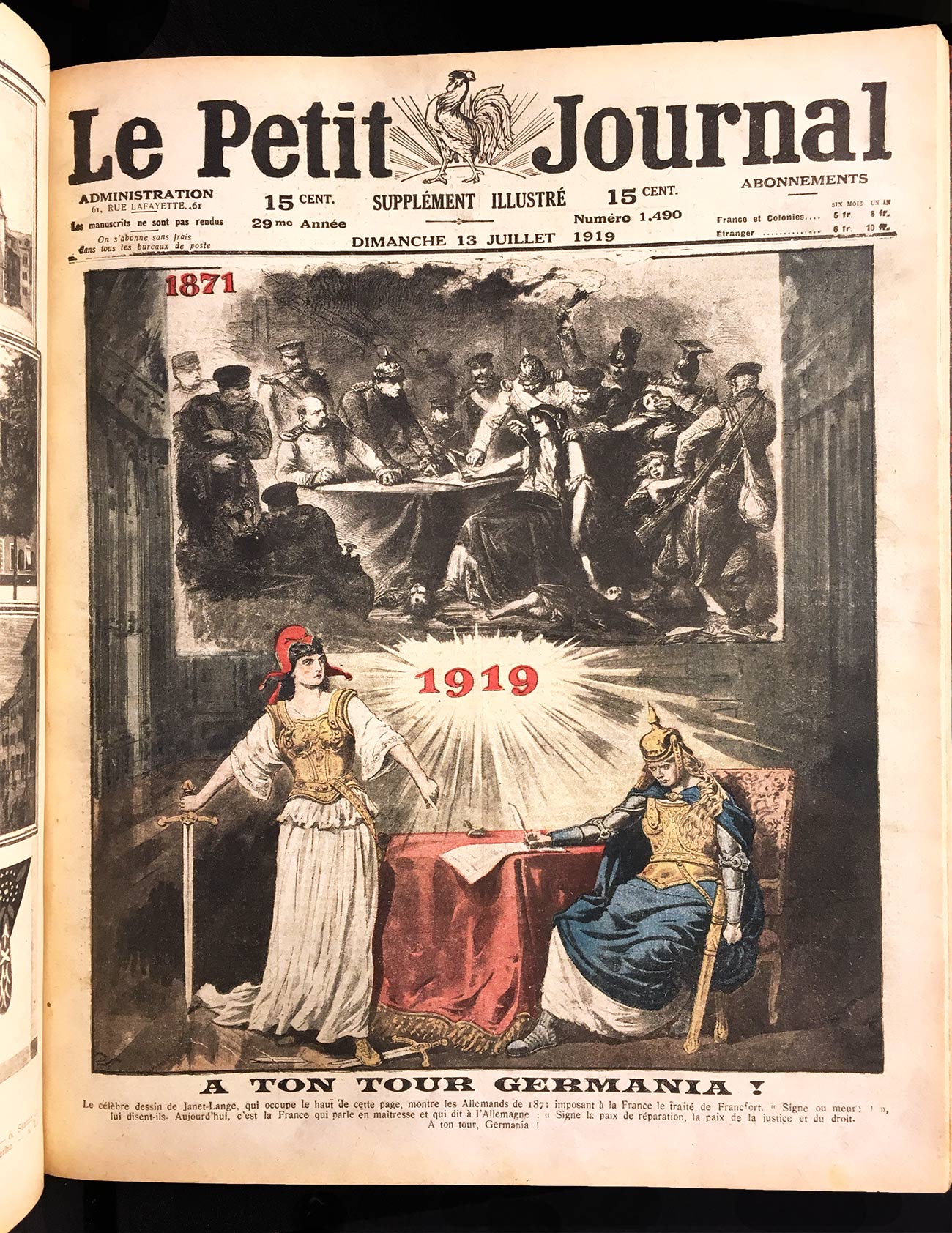

Following the German Empire’s defeat by the Allied Powers in 1918, Alsace and neighboring Lorraine reverted back to France, which was a cause for national celebration by the French. A cover of the French popular journal Le Petit Journal from July 13, 1919, which is included in the exhibition, illustrates the French satisfaction: “A ton tour, Germania / It is your turn, Germania” says a proud Marianne, the personification of the French Republic, pointing to her defeated German counterpart. The background features a gloomy black-and-white scene of the 1871 defeat of France.

“A ton tour Germania” on the cover of Le Petit Journal, July 13, 1919. The Getty Research Institute, 84-S404

Despite this celebratory depiction, the reality for the population of Alsace and Lorraine, once again, looked different. In an attempt to “cleanse” the region of the hated enemy and its cultural influence, the French government immediately started a Francization campaign. Street signs were again replaced, this time by French versions. The German language was forbidden in public in most cities, and laws restricted its use in newspapers.

In addition, the French categorized inhabitants according to their “ethnic purity” and their degree of patriotism and activity under German rule. Many Germans were forcefully deported as a result. Alsace and Lorraine suffered another enforced cultural and linguistic transfer, which would later be reversed yet again with the region’s occupation by Nazi Germany merely twenty years later.

The strained political and intellectual relationship between Germany and France, which suffered enormous damage during the First World War with Germany’s destruction of cultural monuments such as the famous cathedral of Reims, became manifest in the border regions of Alsace and Lorraine and its turbulent, disturbing history. It was not until the gradual reconciliation and rapprochement of the two countries in the post–World War II era that Alsace and Lorraine finally found peace and the region’s identities became independently recognized.

Exhibiting in France

Presenting World War I: War of Images, Images of War to the local audience in Alsace, as well as visitors from France and Germany, required some careful rethinking of the show’s narrative and didactic materials and an adaption to the local context. The exhibition title—now 1914–1918: Guerre d’images, images de guerre—as well as wall texts, labels, and maps had to be translated into French and German, which are both now official languages of the region. Some content, such as the timeline containing the most important names, dates, and battles, had to be updated to reflect the in-depth knowledge of the local audience.

Most importantly, at the Musée Würth France Erstein the exhibition is accompanied by a local addition, the show L’autre guerre: Satire et propagande dans l’illustration allemande, 1914–1918 (The Other War: Satire and Propaganda in German Illustrations, 1914–1918). This exhibition draws from the rich holdings of Strasbourg museums and examines depictions of the war in German postcards, journals, and posters, many of which were either produced in Alsace or distributed to Alsace during the war years in order to raise pro-German sentiment in the region.

The diverse material, which includes many works by local artists such as Hansi, Carl Jordan, Henri Solveen, and Joseph Sattler, testifies to the vital artistic production of the area and traces its particular visual vocabulary and language.

Preparatory design for postcard, 1915, Carl Jordan. Gouache on paper. Photo: Mathieu Bertola/Musées de la Ville de Strasbourg

The carefully assembled and curated exhibition further illuminates several aspects of World War I: War of Images, Images of War, such as the use of animal symbols and stereotyping in propaganda, while also exploring in particular the cultural disruptions, displacements, and national sentiments that characterized Alsace during the First World War.

Interesting collection nicely displayed.