![[Dog sitting on a table]; Unknown maker, American; about 1854; Hand-colored daguerreotype; 1/6 plate, Image: 6.8 x 5.7 cm (2 11/16 x 2 1/4 in.), Mat: 8.3 x 7 cm (3 1/4 x 2 3/4 in.); 84.XT.1582.16](https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/files/2015/06/gm_05620501.jpg?x45884)

Dog Sitting on a Table, about 1854, American. Hand-colored daguerreotype, 2 11/16 x 2 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XT.1582.16

![[Study of a white foal]; Jean-Gabriel Eynard, Swiss, 1775 - 1863; about 1845; Daguerreotype; 1/2 plate, Image: 8.3 x 11.3 cm (3 1/4 x 4 7/16 in.), Object (whole): 14.6 x 18.1 cm (5 3/4 x 7 1/8 in.); 84.XT.255.37](https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/files/2015/06/gm_04459501.jpg?x45884)

Study of a White Foal, about 1845, Jean-Gabriel Eynard. Daguerreotype, 5 3/4 x 7 1/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XT.255.37

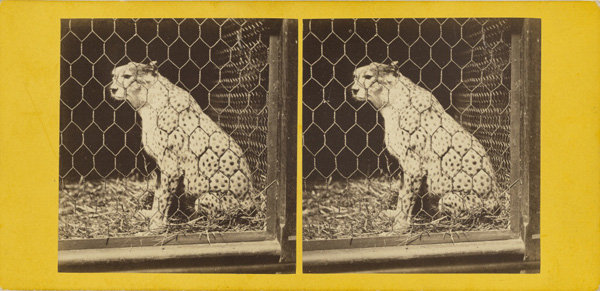

Stereographs were a particularly popular format for early animal photos. A stereograph is two nearly identical prints made with a double-lens camera, which are pasted side by side on a card. When viewed through a stereoscope, the two prints combine to create the illusion of 3D. Photographer Frank Haes made a reputation for himself with his stereographs of exotic beasts at the London Zoo.

The South African Cheetah (Felis jubata), about 1865, Frank Haes. Albumen silver print, 3 3/16 x 6 13/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XC.873.5354

In the early years of photography, even slight movements, such as a wagging tail, caused blurring on plates and paper negatives. Photographing animals in their natural habitats was a major challenge until the late 19th century, when faster film and compact cameras came on the market.

The beginning of the 20th century brought further significant changes, both in people’s views of animals as sentient, complex beings and in camera and film technologies. Photographers could finally achieve precise documentation of complex movement. Alexander Rodchenko, for example, captured a horse in mid-leap, while Harold Edgerton utilized ultra-high-speed strobe lighting to freeze action otherwise invisible to the naked eye, such as this bird in flight. The unusual angle at which these photographers captured their subjects makes for especially dynamic compositions.

Photographers continued to be drawn to animal subjects throughout the 20th century. In the early 1970s, artist William Wegman began working with his newly acquired pet, a dog he named Man Ray in a nod to the Surrealist photographer. Enlisting the canine’s help, he produced a series of staged photographs—at once funny and utterly strange—in which simple tasks are enacted by both the artist and the animal.

In the Box/Out of the Box, 1971, William Wegman. Gelatin silver prints, each 14 x 10 7/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010.85.4.1–2. © William Wegman

More recently, photographers have made work that critiques our relationship to animals and to the natural world in general. Photographer Daniel Naudé recently documented wild dogs in the South African Karoo, an arid region in the country’s interior. He spent time with individual dogs to create a bond that allowed him to get close enough to make photographs from a low vantage point. The series present familiar creatures posed in landscapes that remind viewers of the subject’s ties to the notion of wilderness.

Africanis 17. Danielskuil, Northern Cape, 25 February 2010, 2010, Daniel Naude. Chromogenic print, 23 5/8 x 23 5/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2014.26.1. © Daniel Naudé

Los Angeles photographer Anthony Lepore is fascinated by the notions of nature and wilderness, and how they are used to differentiate between defined spaces where people live and spaces where they do not. His photograph Nightbirds depicts an interior of a visitor center where a scene from nature has been recreated for educational purposes. Replicating the natural world indoors is a challenging enterprise. The smoke detector and lighting fixtures in the background break the veneer of realism—even as we want the illusion to be true.

Nightbirds, 2009, Anthony Lepore. Chromogenic print, 32 x 40 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Gift of Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck, 2014.82. © Anthony Lepore

For more from curator Arpad Kovacs, see the new book Animals in Photographs from Getty Publications.

Comments on this post are now closed.