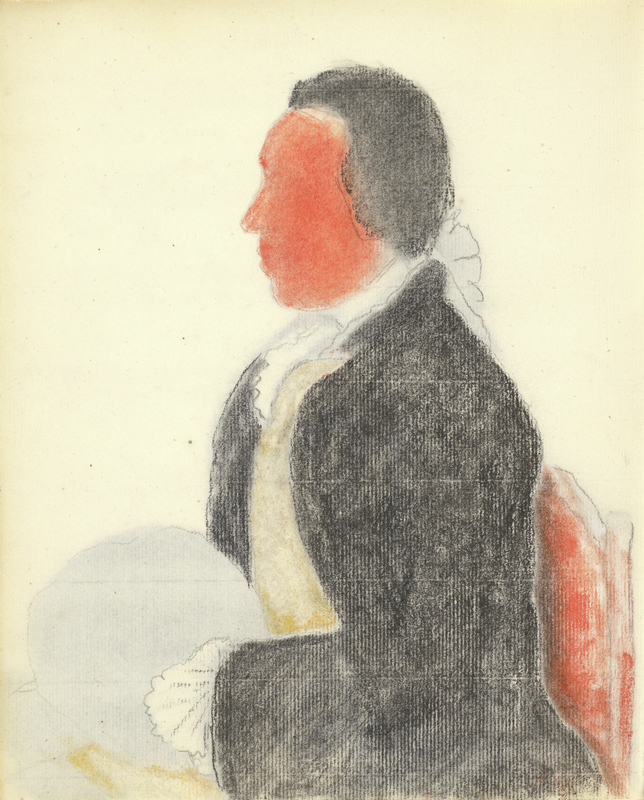

Portrait of Charles Benjamin de Langes de Montmirail, Baron de Lubières, about 1760, Jean-Étienne Liotard. Graphite, pastel with stumping, and red gouache, 8 11/16 x 7 3/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2004.75

Walking through the installation of pastels and drawings by Jean-Étienne Liotard at the J. Paul Getty Museum, you might be surprised to discover an unusual technique displayed in the Portrait of Charles Benjamin de Langes de Montmirail, Baron de Lubières. This drawing, depicting a Swiss historian and man of letters, is exhibited in a special double-sided frame that allows you to see the front and back—recto and verso—of the sheet.

On the recto, the Baron de Lubières is fashionably attired, with his hands enveloped in a warm fur muff. The verso, which usually remains unseen to viewers, is covered in swathes of colors.

Verso Artistry

After drawing the basic outlines of the composition with black chalk, Liotard turned over the thin sheet of cream-colored paper, held it against a light source—perhaps a window—and traced the design onto the back, again using a stick of black chalk. Next, he covered areas of the verso with more black chalk, red chalk, and pastels.

When viewing the front of the drawing, these broadly applied colored chalks are visible, creating delicate tones in the finely detailed composition. The red on the back is particularly effective in rendering the subtle variations of the baron’s skin tone. The double-sided technique, the light palette, and the vivacity and freshness of the entire composition produce a rich and compelling image.

Pastel on the verso (back) of the drawing is visible in the baron’s skin tones

The Ivory Tradition

Liotard derived this artistic method from the miniature ivory painting tradition. In the 18th century, artists created miniature portraits on ivory with watercolor. As the technique developed, the ivory sheets became so thin that they were almost transparent. To make use of this translucency, artists would sometimes apply a silver foil on the back of the portrait to reflect light and give the sitter an almost glowing appearance.

Truly an innovator, Liotard was the first artist to adapt this technique from miniature ivory painting to traditional drawing. In the process, he made a name for himself as one of the 18th century’s most accomplished and sophisticated portraitists.

_______

See this drawing and more in Jean-Étienne Liotard: A Cosmopolitan Artist at the Getty Center, October 20, 2015–April 24, 2016.

Comments on this post are now closed.