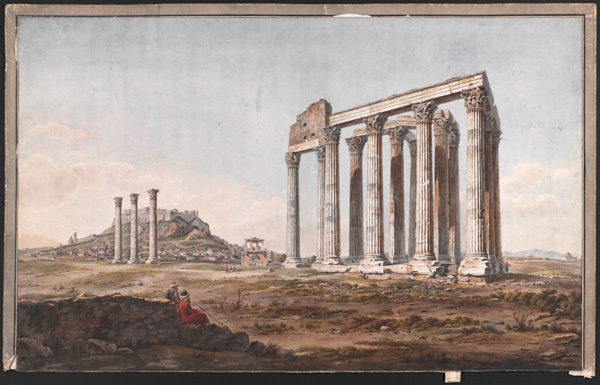

Temple of Olympian Zeus, Athens, 1805, Edward Dodwell and/or Simone Pomardi. Watercolor. The Packard Humanities Institute

When Englishman Edward Dodwell set out on his second expedition through Greece in 1805-6, he and his Italian artist, Simone Pomardi, were in pursuit of “an accurate exhibition of this interesting country, both with respect to its ancient remains and its present circumstances.” Their resulting sketches and watercolors, displayed in the new exhibition Greece’s Enchanting Landscape, more than fulfill this intent. They provide snapshots of the country’s ancient monuments from an era before photography.

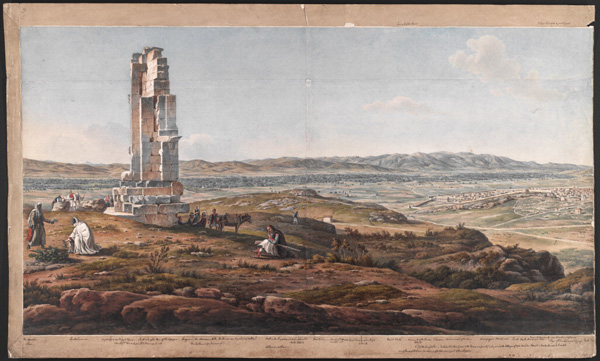

The exquisitely rendered pictures by Dodwell and Pomardi capture the clarity of Greece’s blue sky and the rugged landscape that attracted countless writers and travelers during the nineteenth century. Many of the vistas and prospects in their watercolors have largely been lost today, making these illustrations precious evidence for the appearance of Greece and its villages during the early 1800s.

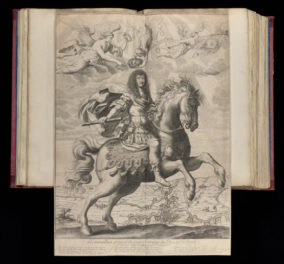

But what has really engaged me in working on this exhibition is Dodwell’s own perspective on traveling through Greece. Thirteen years after concluding his journey, Dodwell published a two-volume account of his explorations, A Classical and Topographical Tour through Greece. (The book has been digitized by the Getty Research Institute, so that it can be downloaded and read at leisure–perhaps even on your digital device for your next trip to Athens).

Digressive, encyclopedic, at times rambling and pedantic, and with a scattering of learned humor (“The forest, which supplied Hercules with his club, could not at present furnish a common walking stick”), Dodwell’s travelogue-cum-scholarly report reveals an abiding passion for the ancient past and an unadulterated delight in being in Greece. These are attitudes to which I would happily subscribe. Flying to celebrate a friend’s wedding on the island of Paros last summer, the first airborne glimpse of the country’s rugged shores prompted a thrill, a flutter of recollections, not entirely dissimilar to those expressed by Dodwell over two hundred years ago:

“I cannot describe the sensations which I experienced, on approaching the classic shores of Greece. My mind was agitated by the delights of the present, and recollections of the past. The land which had been familiar to my ideas from early impressions, seemed as if by enchantment, thrown before my eyes. I beheld the native soil of the great men whom I had so often admired; of the poets, historians, and orators, whose works I had perused with delight, and to whom Europe has been indebted for so much of her high sentiment, and her intellectual cultivation. I gazed upon the region which had produced so many artists of unrivalled excellence, whose works are still admired as the models of perfection, and the standards of taste.”

His prose may sometimes be rather overcooked, but Dodwell offers himself as a perfect companion for exploring Greece. In fact, we’ve quoted many passages from his book on the exhibition labels—who better, after all, to tell us what we’re looking at?

Removal of the Parthenon Marbles by Lord Elgin’s Men, after 1801, Edward Dodwell and/or Simone Pomardi. Watercolor. The Packard Humanities Institute

Erudite and well versed in the classical texts, Dodwell was acquainted with a number of like-minded antiquarians and travelers. Equipped with letters of introduction and a quick and diplomatic mind, he covered a huge amount of ground during his second trip to Greece in 1805-06. He had already witnessed Lord Elgin’s removal of the Parthenon sculptures in 1801, and while his (or Pomardi’s) illustration of this notorious episode presents little in the way of explicit commentary, his later written account leaves no doubt about his feelings on the subject:

“During my first visit to Greece I had the inexpressible mortification of being present when the Parthenon was despoiled of its finest sculpture…It is painful to reflect that these trophies of human genius, which had resisted the silent decay of time, during a period of more than twenty-two centuries, which had escaped the destructive fury of the Ikonoklasts, the inconsiderate rapacity of the Venetians, and the barbarous violence of the Mohamedans, should at last have been doomed to experience the devastating outrage which will never cease to be deplored….”

Dodwell was present in Greece during what proved to be a fascinating and complex phase in the history of classical archaeology, as antiquarians and scholars–men of Dodwell’s ilk–came to the country extolling the grandeur and nobility of its ancient past, seeing what they wanted to see, and, in some cases, taking what they wanted to take.

On occasion, the removal of artifacts was done with the intent of preserving Greece’s heritage in the face of the ongoing use, reuse, and abuse of antiquity by the country’s Ottoman rulers, and Dodwell sometimes found himself caught awkwardly between the two:

“During my residence at Athens, the work of devastation having been begun by the Christians, was imitated in an humble manner by the Turks, and a large block of the epistylia of the Erechtheion at the south-west angle, contiguous to the Pandroseion, was thrown down by order of the Disdar, and placed over one of the doors of the fortress! As I imagined that he intended to demolish other parts of this elegant edifice, which seemed doomed to destruction, I took the liberty of remonstrating at the impropriety of his proceedings. He pointed to the Parthenon! To the Caryatid portico! and to the Erechtheion! and answered, with a singularly enraged tone of voice, ‘What right have you to complain? Where are now the marbles which were taken by your countrymen from the temples?’”

The Erechtheion, Athens, after 1805, Simone Pomardi. Watercolor. The Packard Humanities Institute

In instances like this, we can perceive some of Dodwell’s challenges as he navigated and negotiated (and sometimes bribed) his way as a foreigner among Turks and Greeks. Often this results in near-farce, as when he embraces an official in Athens in order to avoid quarantine, or blunders through bandit-infested backwoods, risking his life and those of his entourage. (A horse, for example, is occasionally reported to have slipped from a precarious path and tumbled down a slope.)

Yet there is also a sensitivity that comes with his keen eye for observation, as when he encounters a household at Kastri, near Delphi:

“The inhabitants of this valley exhibit a people in a state of more inartificial and simple existence than any I have before seen: indeed, they have little to do out of their own valley; and their poverty, while it keeps them at home, affords no inducement for the intrusion of the Turks…The Kastriote women are distinguished by their native beauty, and their unadorned elegance. To fine figures they unite handsome profiles, good teeth, and large black eyes. We went one day to a cottage to inquire for coins; and, making the woman of the house a compliment on her good looks, she seemed highly pleased, and said, she had been handsome, when young, but that it was now her sunset…”

In many situations, particularly regarding the behavior and activity of the Turks, Dodwell’s observations are shaped by his western mindset. Witness his detailed but skeptical account of the dance of whirling Dervishes in Athens, “the most horrid and the most ridiculous ceremony that can be imagined!”

Such comments may leave a sour taste in our mouths today, but they bring to light one of the challenges that Europeans encountered during their travels in the Ottoman Empire. Educated to extol the nobility and virtues of ancient Greece, Dodwell had to relate this perspective to the rather different reality he encountered on the ground: temples left to fall into ruin, once-renowned cities effaced from the landscape, and, perhaps most striking of all, the deprivations faced by the Greek people under Ottoman rule. Dodwell does express his desire for Greek independence, but unlike Lord Byron and others, he seems to have been something of an armchair Philhellene, content to pursue his antiquarian explorations without distraction from contemporary politics.

In the years following the trip, Dodwell’s efforts to produce his book and work up his and Pomardi’s sketches into finished watercolors were truly a labor of love. For all that they reveal of Greece in the early nineteenth century, they also offer something of Dodwell’s sense of himself:

“Having left our ferman, or passport, at Santa Maura, an ill-tempered eunuch who waited on the Bey told him he suspected we were Frenchmen… The Bey, however, was convinced we were English, and when we told him we came for the purpose of seeing the ruins in the vicinity, he laughed, and said our great passion for old stones and walls was quite sufficient to characterize us as Englishmen.”

Dodwell and Pomardi’s exactingly precise watercolors illustrate this passion for old stones, and the sweep of their panoramic views is no less comprehensive and all-seeing than their literary endeavors (Pomardi also published an account of his travels, a year after Dodwell). Viewed side by side in our exhibition, the images and texts not only provide a window on Greece in the years before independence, but also convey the outlook of a young man enthused and inspired by the classical past.

Athens, from Top of Mousaion Hill, Edward Dodwell and/or Simone Pomardi. Watercolor. The Packard Humanities Institute

_______

Greece’s Enchanting Landscape: Watercolors by Edward Dodwell and Simone Pomardi features selections from the vast archive of watercolors and drawings in the collection of the Packard Humanities Institute. The exhibition is on view at the Getty Villa through February 15, 2016.

Comments on this post are now closed.