Getty/ACLS Postdoctoral Fellow Andrew Hamilton discusses his research with Getty Museum curator Bryan Keene.

The primary job of art historians is to research and interpret the world’s artistic legacy. To do that, they might need to travel to remote cultural heritage sites, spend days digging through old archives, examine objects up close, and even learn how to paint, draw, or take photographs in order to better understand what they study.

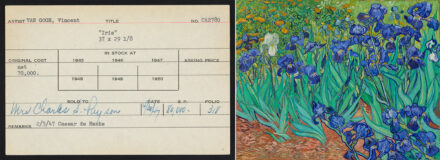

But the primary problem facing art historians is finding enough time and resources to dedicate to that work.

The Getty/ACLS Postdoctoral Fellowships in the History of Art, a partnership of the Getty Foundation and the American Council of Learned Societies, are designed to address that problem for early-career art historians. The yearlong fellowships have no predetermined themes or topics, so recipients can study art from all times and places. And unlike other similar funding programs, the fellowships don’t have a residency requirement: they can be undertaken anywhere in the world. Scholars get the time and support they need to complete a major research project to jump-start their careers.

Andrew Hamilton and Nadya Bair are two of the ten scholars who received funding last year through the Getty/ACLS Fellowship. They completed their projects thanks to the mobility and uninterrupted time the program gave them to do research. With the application period open for a new round of fellows for 2019–20, Hamilton’s and Bair’s experiences remind us what can be accomplished when scholars have the freedom and flexibility to pursue their work.

Learning to Weave the Inca Way

Andrew Hamilton, formerly a lecturer of art and archaeology at Princeton University, spent his fellowship year abroad, engaging deeply with academic and museum communities in Peru and Argentina. His research focuses on the All-T’oqapu Tunic, an intricately woven and high-status Inca garment in the collection of Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, DC. The Incas ceremonially burned the objects they made for their emperor, so the tunic is a rare example of a royal artifact that has survived to today.

All T’oqapu Tunic, Inka, Late Horizon, 1450–1540 CE, wool and cotton, PC.B.518. Photo: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

Western art history has long valued non-Western objects for their aesthetic resemblances to modern and contemporary Western art rather than for their cultural purposes as functional and/or ritual objects. For Hamilton, though, how an object was made and how it was used are critical components of the study of non-Western and pre-Columbian art. “Seeing a tunic hanging behind glass in a gallery does not give you the same understanding of its purpose as seeing it handwoven and then worn, with its patterns gracefully unfolding over the human form.”

Not content to limit his research to reading and looking, Hamilton literally took matters into his own hands. He built a loom and learned to weave. He was careful to replicate Inca techniques so that he could better understand the experience of the original weavers. At the end of his fellowship, he created a digital animation of the experience.

“I wanted to demonstrate the weaving process, since textiles are generally depicted as static, finished forms, and since modern audiences rarely have experience making textiles,” he says. “Taking the tunic out of a flat photo and putting it into an animation is a way to restore its objecthood and make it materially intelligible.”

Andrew Hamilton examines Martín de Murúa’s Historia general del Piru, 1616 (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XIII 16) in the Getty’s Manuscripts Reading Room.

Hamilton also got further insight into the object’s functional use by cross-referencing research materials during a weeklong residency at the Getty, which marked the conclusion of the fellowships. While at the Getty, he examined Martín de Murúa’s Historia general del Piru (1616), an illustrated manuscript in the museum’s collection that chronicles the history of the Inca empire and early Spanish rule. One of its illustrations depicts an Inca king wearing a garment similar in style to the All-T’oqapu Tunic.

“The Getty/ACLS Fellowship gave me freedom to try new methods of research that may also benefit others,” says Hamilton, who takes those methods with him to his new position as associate curator of Arts of the Americas at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Digitally Mapping the Rise of Global Photojournalism

Getty/ACLS Postdoctoral Fellow Nadya Bair

Decades before the Internet could instantaneously splash news images into every corner of the world, the Magnum Photos agency—one of the first agencies to be owned and administered by photographers—was created to supply magazines with global photojournalism. During her fellowship, Nadya Bair completed The Decisive Network: Magnum Photos and the Postwar Image Market (forthcoming from University of California Press in May 2020), the first scholarly monograph on the early history of the agency.

Bair, a postdoctoral associate in digital humanities and American studies at Yale University, spent her fellowship year studying how the European market impacted Magnum’s commercial success. At the National Library of Paris, she sifted through archives of illustrated magazines such as Paris Match and Epoca, French and Italian outlets to which Magnum sold its pictures.

A Magnum Photos meeting in Paris, 1950. From left to right: Robert Capa, Maria Eisner, Alberto Mondadori, Ernst Haas (standing), George Rodger, Joan Bush, David Seymour, Leonard Spooner, Werner Bischof. Courtesy Magnum Photos

“People are increasingly studying the transatlantic circulation of images, and Magnum is key to that story,” says Bair. “But it’s not enough to look at one magazine or even one agency. I compared what I learned in Magnum’s internal archives to hundreds of magazines published across Europe. And patterns emerged: I realized who was selling to whom and when, and saw that photojournalism was already a standardized and international industry in the late 1940s.”

Nadya Bair’s data visualization of Magnum Photos’s agent network in Europe.

While cataloguing Magnum’s European operations, Bair created digital maps and data visualizations that revealed the agency’s vast networks. Among these networks were the agency’s clients and staff, the latter of which included many women vital to Magnum’s operations. Bair found herself wanting to write about these women, who—in addition to helping Magnum photographers in the field—archived, sold, and edited the photographers’ work.

“The digital visualizations helped me realize there was a story I needed to better narrate,” says Bair. As a result, she synthesized her findings and added a section on the women to a new first chapter of her book. “All my changes were based on my fellowship. And I’m hopeful that my research will open the door for other scholars to take a closer look at postwar European photojournalism.”

The 2018–19 class of Getty/ACLS Postdoctoral Fellows.

The application for 2020–21 Getty/ACLS Fellowships is open through October 23, 2019. Learn about other past fellows and how to apply.

Comments on this post are now closed.