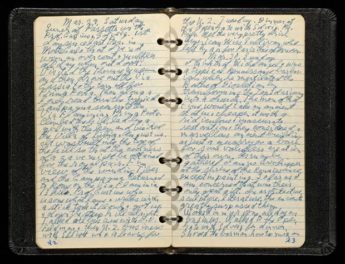

Man One in the library at the Prehen house

“What I liked about the Book of Friends is that it’s an idea that’s centuries old, but modern graffiti artists have been keeping the tradition alive through the common practice of ‘getting up’ on black books. Who would have thought that an inner city art form would be responsible for continuing a tradition begun hundreds of years ago by nobility?”

These were the thoughts of artist Man One when we asked him a few questions about helping to make the Getty Graffiti Black Book, officially known as LA Liber Amicorum—both as a creator and as a curator who recruited 19 other artists to fill pages for this multi-voice, multi-media compendium of street art. We got some great responses from the other Los Angeles graffiti and tattoo artists involved, too, especially surrounding that age-old art historical argument, form versus content.

What’s more important, the style or the message?

Gorgs: The style is the message.

Page by Gorgs from the artists’ book L.A. Liber Amicorum

Prime: The message, because if your message is lousy, all the typography in the world won’t help one bit.

Defer: I think both are important, but I must say that I would like to see more messages in art these days. I think before art was used more as a vehicle to relay a message or statement to the viewer.

Page by Prime from the artists’ book LA Liber Amicorum

Eye One: They are intrinsically linked. Everything conveys a message.

Angst: I don’t believe it’s an either/or. It’s more akin to and or in addition to…A message with no style comes across as propaganda, whether personal or political (i.e., “dumb,” or without human ingenuity). But style with no message appears as mere decoration (i.e., vacuous and superficial, without human depth).

Page by Defer from the artists’ book LA Liber Amicorum

We also asked the artists about street art in Los Angeles, and weren’t surprised that there was little agreement on that subject, either.

What is “L.A. street art” to you? How is it different here than in other cities?

Page by Eye One from the artists’ book LA Liber Amicorum

Prime: It is the voice of the individual who seeks to reach those who question the norm.

Defer: To me, street art is a broad term that covers so many areas. Before, it was mainly graffiti, but now it seems to be used for anything even remotely related to graffiti. I think L.A. has its own distinct style or identity that is now recognized throughout the world. It’s a hybrid of traditional placaso hand styles, Old English fonts, and traditional New York graffiti styles.

Page by Angst from the artists’ book L.A. Liber Amicorum

Eye One: “L.A. street art” is a bit of a misnomer, especially in its current use in the context of graffiti. I consider the entirety of the public space as a container for “art in the streets.” The transition of the northbound 110 carpool lane to the westbound 105 is street art. The Griffith Observatory is street art. The Chicano murals of the ’60s are street art.

Angst: Yikes, such an open-ended, all-encompassing question! If you mean L.A. graffiti, which pre-dates the current handle of “street art,” I would say, to me, it’s gang graffiti. There is no pretense in gang writing. It’s not trying to be “art,” much less “street art.” It’s different here than in other cities because gang graffiti is homegrown, not imported. It’s a direct assertion of place and environment as expressed by L.A. youths. It’s a historic, vibrant, living heritage conveyed in practice on public walls. Even if the style is adopted and tweaked by other locales, it’s derivative of “here.” And “here” is important.

Where there was more agreement was around the experience of seeing rare books from the 1500s, 1600s, and 1700s, which curator David Brafman selected for the artists during their visits to the Research Institute.

What was your experience of discovering the rare books at the Research Institute?

Top: Page by Rick Ordoñez from the artists’ book LA Liber Amicorum Bottom: Theodor de Bry, Emblemata nobilitati et vulgo… (Frankfurt, 1592). The Getty Research Institute, 2903-720

Prime: Mesmerizing—I was almost in disbelief that these books had been so well preserved. Some went back 300, even 400 years. Their beauty is timeless.

Eye One: I was blown away by all the books presented to us in relation to this project. I am fascinated by typography and letterforms, and seeing such a vast wealth of unique works really impressed me. Johann Heinrich Gruber’s Liber Amicorum (1602–12) is an amazing antecedent to the work graffiti writers do in black books. I appreciate the Getty’s understanding of the lineage graffiti shares with such a volume. It relates directly to my black books, as I have always asked friends, peers, and colleagues to contribute work to their pages.

Angst: I was in awe at the palpable “life” present in the work, and in the rare books that I saw at the Getty. By which I mean I was electrified, and humbled, to hold the hand-crafted books in my hands and turn their pages, as well as to be able to look closely and study the pages/drawings/manuscripts.

I related to these rare books as one who recognizes a colleague in arms. Had I been born in an earlier age, I would’ve been a scribe, and I examined these books with a scribe’s eye and hand. It was wonderful to retrace with my finger the previous hand of a long dead scribe or artist who drew, wrote, and made the choices or decisions on the page regarding the scale, weight, composition, unity, consistency, spacing, of the letters and images.

Page from Geoffroy Tory, Champfleury (Paris, 1529). The Getty Research Institute, 84-B7072

Text of this post © J. Paul Getty Trust. All rights reserved.

To browse all 143 pages of the Graffiti Black Book, including more of the rare books that inspired it, and to see the full list of contributing artists, see this page.

Amazing work.

Is this book published and available for purchase?