Scan of a Knoedler stock book noting inventory of paintings by Gérôme, Bouguereau, and others. The Getty Research Institute, 2012.M.54

The Getty Research Institute has launched an expanded dealer stock book database that provides free online access to almost 24,000 records created from the Knoedler Gallery painting stock books. Books 1 through 6, dating from 1872 to 1920, are available now; stock books 7 through 11 will be added soon. You can explore the records from the Knoedler stock books here.

Knoedler Gallery in New York was a central force in the evolution of an art market in the U.S. This newly enhanced database can be used to reconstruct the itineraries of thousands of paintings that crossed the Atlantic during the Gilded Age—including many that ended up in major American museums.

Creating the Database

Screenshot of Jean-Léon Gérôme record in the Stock Books Database, Getty Provenance Index®

Records in the database were created by transcribing handwritten entries in the original ledgers preserved at the Getty Research Institute. To facilitate searching, editors of the Project for the Study of Collecting and Provenance (PSCP) then reviewed and enhanced these records by adding subject classifications, and validating artist names against an authority database listing variations of the ones found in the books. More research and standardization work will be done on buyer and seller names toward the end of this two-year project. But it seemed appropriate to respond to the demand of the scholarly community as fast as possible.

Together with over 43,700 records from another prominent gallery, Goupil & Cie and Boussod, Valadon & Cie in Paris (1846–1919), which have been online since 2011, this expanded database forms an important subsection of the Getty Provenance Index®. While the Knoedler stock books were being transcribed and edited, Ruth Cuadra, an application systems analyst in the Research Institute’s Information Systems Department, worked to adapt the Goupil database design to accommodate the new Knoedler data. One special feature of the new design allows researchers to link Goupil stock numbers found in Knoedler records with the original Goupil records.

Why Study Stock Books?

The transactions of art galleries remain to a large extent secret. Buyers and sellers typically put a high value on discretion, making it hard to reconstruct who bought what, when, and for what price. Dealer stock books, which include information such as purchasers’ names, sale dates, and selling prices, are among the most precious source documents for research in the history of collecting and art markets. However, as suggested by Paul Durand-Ruel, legendary promoter of the Impressionists, rare were the art dealers who kept systematic records of their transactions. In the case of 19th-century gallerists, even when they recorded their inventories in stock books, those books rarely survive. The business archives of several Goupil competitors, including Charles Sedelmeyer, Louis Martinet, and Georges Petit, seem to be lost forever. No one thought this material important enough to save.

Only recently have some crucial dealer archives of the period become publicly accessible: the National Gallery, London, acquired the papers of Thomas Agnew and Sons, and the Colnaghi archive just moved from an inaccessible warehouse in the east of London to Waddesdon Manor, a Rothschild estate, an occasion that is being celebrated with a conference on “Art Dealing in the Gilded Age” this week. Starting in October at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, a Durand-Ruel exhibition taking advantage of his archive will tour Europe and the United States.

The Getty Research Institute acquired the M. Knoedler & Co. archive in 2012, uniting it with the Institute’s extensive holdings of important dealer materials in the Special Collections such as those of Duveen Bros., Goupil, Boussod & Valadon, Arnold et Tripp, and many others.

Paintings Imported by Knoedler

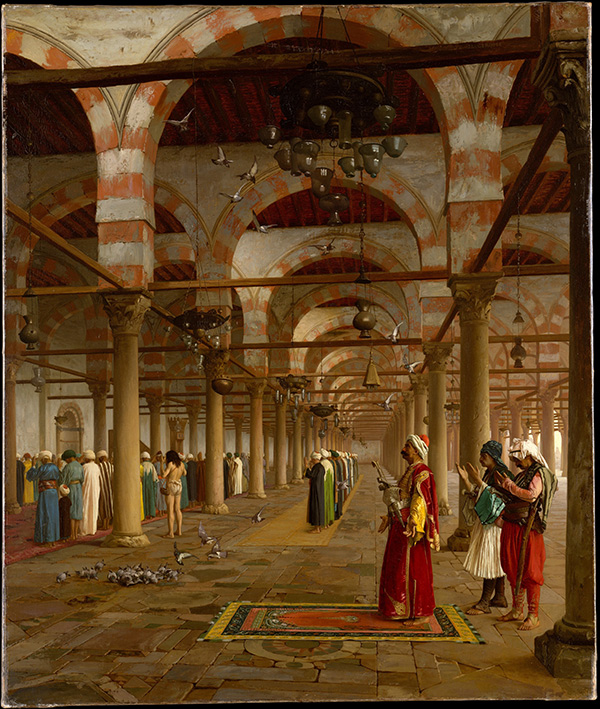

Prayer in the Mosque, 1871, Jean-Léon Gérôme. Oil on canvas, 35 x 29 1/2 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 87.15.130. Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Bequest of Catharine Lorillard Wolfe, 1887

The Knoedler Gallery was founded in 1848 as the New York branch of Goupil & Cie, but became independent in 1857. Although Knoedler’s stock books start much later, we still find paintings on consignment with Goupil inventory numbers in the first volumes dating to the 1870s.

For example, an 1871 painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme, Prayer in the Mosque, shows up in the stock books of both Goupil and Knoedler. Goupil acquired the painting directly from the artist, his son-in-law, on September 23, 1874 for 20,000 francs and sent it on commission to Knoedler by doubling the price (40,000 francs, or about 8,000 dollars). Two months later Knoedler managed to sell it to New York collector Catharine Lorillard Wolfe for $10,670, netting a profit of at least $2,000. In 1887 Wolfe bequeathed the painting to the young Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Knoedler, like Goupil, initially catered to the taste for anecdotal genre paintings among U.S. collectors. But in the 1890s they began to shift their emphasis toward Old Master paintings. Henry Clay Frick, whose mansion ended up being just a stone’s throw away from the Knoedler Gallery on E. 70th Street in New York City, acquired a large portion of his famed Old Master collection from Knoedler. The database lists 171 paintings bought by Frick from Knoedler, many now held in the Frick Collection, including Bellini’s Saint Francis in the Desert, Goya’s The Forge, Vermeer’s Officer and Laughing Girl, a Rembrandt self-portrait, and Veronese’s Allegory of Virtue and Vice.

A Who’s Who of Art Collecting

The Knoedler database is a who’s who of art collecting in the Gilded Age, providing a glimpse of the origins of the great American art museums. Besides Frick, we find the names of the Vanderbilts (55 paintings), Jay Gould (47 paintings), Andrew Mellon (45 paintings), William Andrew Clark (34 paintings), Charles Crocker (33 paintings), the Huntingtons (29 paintings), Benjamin Altman (27 paintings), the Rockefellers (26 paintings), Peter Arrell Brown Widener (18 paintings), William T. Walters (17 paintings), and Potter Palmer (15 paintings).

The Getty Research Institute’s expanded database of dealer stock books gives researchers the opportunity to study all of Goupil and Knoedler sales records in the aggregate. New possibilities for research abound. Scholars can now analyze the relationship between consumer preferences and prices on thousands of transactions, thus revealing larger patterns and trends in the art market around 1900. They might calculate inventory turnover rates to give an indication of the gallery’s volatility or visualize dealer networks to study the question of how artwork crossed national borders over time—as has been attempted with Goupil data in two recent studies, Art Dealers’ Strategy and Local/Global: Mapping Nineteenth-Century London’s Art Market.

We are working on creating digital records for stock books 7 through 11 and will update this post when they become available.

Thanks to the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, whose grant support enabled this project.

When will the photographic images of the artwork/paintings in the Knoedler archive be cross referenced to the ledger book entries?

Hi Alexander, We intend to cross-reference to other material in the archive including images, but we have not yet made a clear plan for that; when we have more details, we will post them here. —Annelisa / Iris editor

Dear Annelisa– do know where I may be able to find archival photos of the Knoedler Gallery, including images of exhibitions, purchased works, etc? Thanks

Hi Eloise, Thanks for your interest in the Knoedler archive! Senior cataloguer Karen Meyer-Roux shared this info: The photographs haven’t been cataloged yet; after the cataloging of the vast correspondence (1626 boxes), the photographs are the next group of materials that is being cataloged. As this portion of the archive is nearly as large as the correspondence, we presume that they won’t be available for a year still.

Update: The photographs will be available in December 2015.

Hi Annelisa,

Are these photographs now available?

Thank you for your hard work cataloging this amazing piece of history!

There are now 1149 boxes of photographs available for research in the Reading Room of the Getty Research Library. The Getty Research Institute plans on digitizing selected photographs from this portion of the archive through December 2016. This means a specific box may be unavailable for a short period. Please contact the GRI to ensure that the specific boxes you need to consult are available before visiting the Getty Research Library’s Reading Room.

Is there anything about sculpture sales? I am doing a Census of French sculpture (1500-1960) in American public collections (soon online: frenchsculpture.org) and Knoedler has dealt Rodins, in particular. Thank you.

Sorry, just saw the 16 items online.

I am researching the collections of Marcus and Walter Samuel the 1st and 2nd Viscount Bearsted who painting collections in the UK and at LA SERENA AT ST JEAN CAP FERRAT FRANCE. I am very interested in the latter collection. Can you help please

Victor ince

“PI Record No. G-8240 // Stock Book Goupil Book 5, Stock No. 5443, Page 125, Row 7 // Artist Name(s) LEBEL, ANTOINE (French) / from stock book: Lebel”

contains an error. The artist, as noted down in the stock book, should be FORTUNY

I have also encountered a problem with the custom display: the SALE DATE does not seem to load

That is my new email address. OK here goes again

I need provenance of Rodin’s marble bust of Countess of Warwick, from 1913 when she had it to stock book Francis H. Howard (London), Knoedler #14051, entry date 1917/12/29

Dear Maxine,

Christian Huemer, whom you wrote to, took on a new position in Vienna, Austria, and may not read the comments on his Getty blogs. Did you find the information for your provenance question?

My understanding of your question is that you are only interested in the provenance between the time the bust belonged to Countess of Warwick to 1916/12/29, when it was acquired by Knoedler. My reading of the transaction date is 1916/12/29, rather than 1917/12/29, see folio 139 of the stock book which is available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/2012m54b6.

The very brief information related to the transaction suggests that Francis Howard served more as an agent than as a collector or owner of the bust at the time of the transaction, even if it is his name that appears in the stock book. In addition there appears to have been a disagreement between Lady Warwick and Knoedler on the value of the bust. This is my understanding of the following sentence. It is a line written by Knoedler’s New York office to its London office stating “We confirm our cable saying that Howard wrote us that Lady Warwick wants twelve hundred pounds for her marble bust by Rodin, and that we would give eight hundred for it. Naturally in the event of our purchasing this you will ship it immediately.” This is the only information I was able to identify that could address your question.

The other provenance information we have relates to the sale on February 26, 1917, in New York by Knoedler to John M. Cormack who, unfortunately for Knoedler, returned the bust several days later to the firm and received credit, see folios 90 and 95 of the sales book available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/2012m54b71.

I hope this answers your question.

Best wishes,

Karen Meyer-Roux

Dear Karen

Thank you so much for the information. From what I understand from you Lady Warwick had the bust until 1916/12/29 when Knoedler acquired it. Is that correct? Then Knoedler sold it to Cormack on 2/26/1917 who returned it. Then it was bought by Robert Edwards on 1917/05/00 for 15000 dollars. That brings it up-to-date for me.

Note: How do I get to the folios once I’ve reached the http address?

Dear Maxine,

This note written by Knoedler staff seems to further support the fact that staff at the firm believed Lady Warwick to be the main custodian of the piece. On 12/14/1916, Knoedler staff writes that “I heard from Francis Howard on Saturday last that Lady Warwick would accept £800 … and would be looking forward to receiving the money before Christmas.” However on 12/21/1916, they write “we gave Mr. Howard a cheque made to his order, at his request, for the Rodin bust” (emphasis mine). The records of the firm are a good source for understanding the firm’s actions in the transaction, but not a good source for understanding what may have happened outside of the firm’s control, such as an arrangement between Francis Howard and Lady Warwick or what happened to the bust before it entered the firm’s stock.

I believe the purchase of the bust by Robert J. Edwards took place on May 14, 1917. See folio 114 of the sales book available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/2012m54b71.

If you have difficulties with the use of databases at the Getty Research Institute or have further questions, you can also make enquiries at the following contact information:

General Question

Provenance Research Question

I hope this helps.

Best wishes and happy holidays,

Karen