“The tree that rustles and the heather that grows is for me a grand history, that which will not change; if I speak their dialect well, I will have spoken the language of all times.” —Théodore Rousseau

As a member of the Getty’s paintings department, I had the chance to watch the installation process for the exhibition Unruly Nature: The Landscapes of Théodore Rousseau. I was excited to see the work of a celebrated artist I still knew little about—and surprised to find that it was an unfinished oil painting, rather than a complete masterpiece, that first caught my eye.

Felling Trees on the Ile de Croissy, tellingly known as Massacre of the Innocents in the nineteenth century, was upon its uncrating the most confrontational work in the gallery. In contrast to the romantic and stormy Mont Blanc Seen from La Faucille just across the room, the painting is a rather a grim depiction of destruction as a group of men haul down trees with rope.

The expressiveness of the browns, grays, and greens in this work is striking, and Rousseau’s careful detailing of the trees contrasted sharply against his rather sketchlike elaboration of the actual humans. The invocation of innocence massacred intrigued me, so I began my research on an artist who, as I soon learned, was deeply committed to depicting nature’s power.

The Rock Oak (Forest of Fontainebleau), about 1860–67, Théodore Rousseau. Oil on panel, 35 × 46 in. Private collection

Though Rousseau meticulously worked up his paintings in the studio, his expressive technique recreates an uncultivated and unidealized experience of the world. Every detail is a personal invitation to explore nature’s inner workings. The Rock Oak, densely packed with masses of leaves, moss, and gnarled branches, is difficult to read at first glance. A frenzy of greens and oranges compel us to explore the texture of forest floor, while careful white dabs record minute light effects on the grey tree trunks. Our eyes find only tiny patches of blue sky in the background, while pops of color in the forest’s dark corners lure us further into its depths. In many of Rousseau’s paintings, the act of looking is a reward in itself.

Edge of the Forest, Sun Setting, 1845–46, Théodore Rousseau. Oil on canvas, 16 1/4 × 24 3/4 in. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, LACMA, Purchased with funds provided by the William Randolph Hearst Collection by exchange

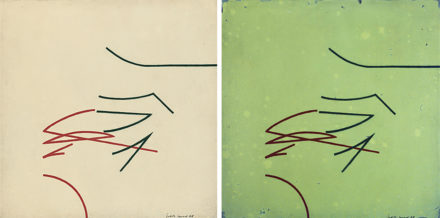

Trees, which Rousseau called the “noble victims” of man’s destruction, were one of the artist’s favorite subjects. In Edge of the Forest, Sun Setting, one tree stands in the aftermath of a harvest as the torn limbs of its companions lay scattered on the ground. Particularly disturbed by modern forestry practices, Rousseau here presents a picture of defiance. The main tree stands slightly off center, its sharply silhouetted branches bending dramatically to one side. Wild and unruly, it seems to rebel against the orange sky.

Rousseau often placed his subjects at times and sites that also suggest physical transition: sunsets, forest edges, marshes between dry plains and mountainous terrain. The potential for transformation, for creation to rise from destruction, is enhanced by these powerful spaces. Like many of Rousseau’s paintings, Edge of the Forest walks a fine line between hushed solemnity and reverent ode.

Rousseau’s landscapes are also striking for what art historian Greg Thomas calls their “earth narratives,” which highlight the ecological link between life and death in the universe. In Edge of the Woods, orange trees shed their brittle leaves onto a marshy plain below. A group of villagers gather sticks while a donkey trudges through the mud. This would be melancholy scene of autumnal death were it not for the fullness of the wet earth, waiting patiently to fertilize another spring, set under a sky that is both cool and warm. One tree rises from the edge of the forest, arching triumphantly against the clouds.

Rousseau also enjoyed adding small human figures—often rendered as quick dabs of red, black, or white far into the background – to provide scale for his environmental drama. Tiny and easily missed at first glance, these peasant figures recede quietly into the scene, suggesting a harmonious relationship between man and nature. Rather than the civilizing narrative of many landscapes that include human beings, Rousseau’s figures are only small actors, outscaled on nature’s grand stage.

Forest of Fontainebleau, Cluster of Tall Trees Overlooking the Plain of Clair-Bois at the Edge of Bas-Bréau, Théodore Rousseau. Oil on canvas, 35 3/4 × 46 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007.13. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

In 1852, moved by the destructive effects of a growing tourist industry, Rousseau petitioned Emperor Napoleon III to protect cherished parts of France’s Forest of Fontainebleau by imperial decree. Twenty years before the creation of Yellowstone National Park, that order was signed, and Rousseau became one of the world’s first preservationists. As illustrated in his pictures of the forest and other French sites, Théodore Rousseau painted the world just as he lived it: with a deep reverence for the earth, its powers, and its rights.

Forest of Fontainebleau, Cluster of Tall Trees Overlooking the Plain of Clair-Bois at the Edge of Bas-Bréau (detail), Théodore Rousseau. Oil on canvas, 35 3/4 × 46 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007.13. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Comments on this post are now closed.