Left: The Virgin and Child with Saints and Allegorical Figures, about 1315–20, Giotto di Bondone (Italian, about 1267–1337). Tempera and gold leaf on panel. Private Collection. Courtesy of Wildenstein & Co., Inc., New York. Right: The Crucifixion, about 1315-20, Giotto di Bondone. Tempera and gold leaf on panel. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg, photo M. Bertola

There’s been almost seven hundred years of chatter about Giotto di Bondone (about 1267–1337), a painter from Florence considered one of the greatest artists of all time. After six years of careful planning and negotiation, we at the Getty Museum are excited to share seven of his works in the exhibition Florence at the Dawn of the Renaissance: Painting and Illumination, 1300–1350, opening November 13. This group of paintings represents an unprecedented number of works by Giotto in a North American exhibition. After all, there are only five paintings by Giotto in North American collections—and four of them will be on view at the Getty, alongside an impressive gathering of over 90 paintings and illuminated manuscripts from early Renaissance Florence.

As a leadup to the November opening, let’s take a look at what people have said about Giotto.

During his lifetime, Giotto was heralded as an artist who revived the art of painting, which some felt had fallen into ruin over the course of the Middle Ages. He was famous for painting on a monumental scale, demonstrated by his majestic frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. Ever since the 14th century, Giotto’s name has been synonymous with the early Renaissance in Florence, and his reputation has cast a long shadow on the art of the period. Writers such as Giovanni Boccaccio and Giovanni Vilanni, who were contemporaries of Giotto, championed his ability to depict the human figure as a believable form with mass, as if drawn directly from nature.

Giotto, they said:

“…brought back to light an art which had been buried for centuries…So faithful did he remain to Nature…that whatever he depicted had the appearance, not of a reproduction, but of the thing itself, so that one very often finds, with the works of Giotto, that people’s eyes are deceived and they mistake the picture for the real thing.”

—Giovanni Boccaccio, Decameron VI, 5“The most sovereign master of painting in his time, who drew all his figures and their postures according to nature. And he was given a salary by the commune in virtue of his talent and excellence.”

—Giovanni Villani, Nuova cronica

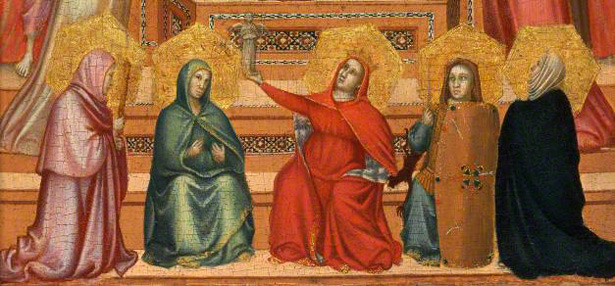

The Virgin and Child with Saints and Allegorical Figures (detail), about 1315–20. Giotto di Bondone (Italian, about 1267–1337). Tempera and gold leaf on panel. Private Collection. Courtesy of Wildenstein & Co., Inc., New York

The above detail demonstrates Boccaccio and Villani’s points. Notice how Giotto painted the garments of these five female personifications of the virtues by applying subtle variations of color to create a sense of volume in the fabric, thereby revealing the figures’ bodies underneath: the contour of an elbow, the curve of a shoulder, the bulge of a knee.

Another of the earliest writers to evaluate Giotto’s art was Dante Alighieri, author of the famed Divine Comedy. Here’s what Dante wrote in the second canticle, Purgatory:

O empty glorying in human power!

How short a day the crown remains in leaf,

If it’s not followed by a duller age!

In painting it was Cimabue’s belief

He held the field; now Giotto’s got the cry

And Cimabue’s fame is dim…”

—Dante Alighieri, Divine Comedy, Canto XI, lines 91–95

Some explanation is probably in order. Cimabue is considered the master artist who trained Giotto in the art of painting. According to Dante, Giotto’s reputation had eclipsed Cimabue’s, despite the fact that Cimabue was also considered a revolutionary painter at the time (read more about Cimabue here). Take a look below at a famous comparison between the two artists and keep the images in mind as we hear from others who have written about Giotto. Note, for example, in Cimabue’s painting how the garments worn by the Virgin and Christ shine with golden lines, known as chrysography, a stylized feature common in Byzantine paintings. The figures in Giotto’s image, by contrast, appear sculptural, having rounded forms and a clear sense of weight.

Left: The Virgin and Child Enthroned with Angels and Prophets, about 1285–86. Cimabue (Italian, about 1240–1302). Tempera and gold leaf on panel. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence (inv. 1890 n. 8343). Right: The Virgin and Child Enthroned with Angels (Maestà), about 1306–10. Giotto di Bondone. Tempera and gold leaf on panel. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence (inv. 1890 n. 8344)

Around the year 1400, Cennino Cennini authored one of the most important early treatises on artist practices. Writing about Giotto, Cennini noted that the elder artist “translated the art of painting from Greek to Latin.” By this he meant that Giotto had moved away from the “Byzantine” manner of painting, often characterized by stylized forms, patterning, flatness, and otherworldly-looking figures. Lorenzo Ghiberti, the great sculptor, wrote similarly that Giotto’s art rejected the Byzantine style and returned to the rumored excellence of ancient Etruria and Rome. When we compare Giotto’s Madonna and Child (below right) with a Byzantine icon from the end of the 1200s (below left), we can see how Giotto uses light and shade to suggest musculature, and how he depicts subtle expressions on the faces of both Mary and the Christ Child.

Left: Madonna and Child (detail), unknown artist, Byzantine, about 1290. Tempera and gold leaf on woven fabric over wood. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.1. Right: The Virgin and Child (detail), about 1320/30, Giotto di Bondone. Tempera and gold leaf on panel. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1939.1.256

Filippo Villani, a descendent of Giovanni Villani (mentioned earlier), wrote this account of Giotto’s ability to convey emotion:

For pictures formed by his brush follow nature’s outlines so closely that they seem to the observer to live and breathe and even to perform certain movements and gestures so realistically that they appear to speak, weep, rejoice and do other things.” —Filippo Villani, De origine civitatis Florentiae et euisdem famosis civibus

In Giotto’s Crucifixion the Virgin Mary, overcome by sorrow, collapses into the arms of two other women. Across the way, John the Evangelist clasps his hands to his face in mourning as one man points and others gaze upon Christ’s lifeless body.

The Crucifixion (details), about 1315–20, Giotto di Bondone. Tempera and gold leaf on panel. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg, photo M. Bertola

Any discussion about Italian Renaissance art, especially Florentine, must include a nod to Giorgio Vasari, whose Lives of the Most Excellent Italian Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550 and 1568) has long informed our understanding of art made in the period from Giotto to the mid-16th century. Here are his words in praise of Giotto:

“That very same debt painters owe to nature…is also owed, in my opinion, to Giotto, the Florentine painter; for when the methods and outlines of good painting had been buried for so many years by the ruins of war, he alone…revived through God’s grace what had fallen into an evil state and brought it back to such a form that it could be called good.”

—Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Excellent Italian Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

In the modern era, beginning in the 19th century with scholars such as Jacob Burckhardt and John Ruskin, and continuing into the 20th with art historians Richard Offner, Roberto Longhi, Millard Meiss, Luciano Bellosi, and Miklós Boskovits, among others, scholarship on Giotto has sought to more clearly understand the extent of his artistic production. In 1937, for example, the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence presented the exhibition Mostra Giottesca, which placed works by Giotto in the context of painting, sculpture, drawings, liturgical objects, and illuminated manuscripts from the late 13th century to the mid-14th. There have been several “Giotto” exhibitions in Europe since 1937, and most follow a similar format and bring together the same vast range of art objects in different media. We hope that the focus of the Getty exhibition on panel paintings and illuminated manuscripts will enrich our understanding of Giotto’s influence as well as our appreciation of his equally innovative contemporaries.

The two paintings shown at the top of this post will be featured in the exhibition Florence at the Dawn of the Renaissance. Now in separate collections but once forming a devotional diptych roughly the size of a laptop computer, the paintings will allow visitors to study Giotto’s monumental approach to painting on a small scale. Combined with objects by artists who worked as both panel painters and manuscript illuminators, we hope that the exhibition will inspire a new understanding that Giotto’s revolution in painting was not limited to the large scale—and we hope that the pairing of objects will encourage a new appreciation for manuscript illuminators at this crucial moment in the early Renaissance. We look forward to what you will have to say about Giotto.

The Virgin and Child with Saints and Allegorical Figures (detail), about 1315–20, Giotto di Bondone (Italian, about 1267–1337). Tempera and gold leaf on panel. Private Collection. Courtesy of Wildenstein & Co., Inc., New York

To explore more riches from the upcoming Florence show, see exhibition curator Christine Sciacca’s post about the most prolific illuminator in Florence from the time of Giotto, and another star of the exhibition, Pacino di Bonaguida.

Mr. Keene, this is a wonderful essay. Thank you so much. I cannot wait for the exhibit to open!

I am doing a project for my art class and wanted to know why the Christ child has a red ribbon in his left hand in the painting of Madonna Child, Byzantine about 1290 on your page.

Thanks

Left: Madonna and Child (detail), unknown artist, Byzantine, about 1290. Tempera and gold leaf on woven fabric over wood. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Andrew W. Mellon Collection, 1937.1.1.

Everybody is talking about Giotto. They don’t know, however, that his frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel are copies of the religious dramas scenes presented on an outdoor wooden stage. I can demonstrate with rare, illustrations never published before that two permanent components and three variable accessories of the wooden stage are VISIBLE in all the frescoes. I have just completed a study, and those who email me will read it.

I am Ubaldo diBenedetto, Ph.D. I have taugt Renaissance art at Harvard University for thirty-three years.

In my study published by the University of Turin supports Emile Male’s theory that “the theater influenced painting, and not the other way around.”

Giotto copied the scenes for the sacre rappresentazioni, the miracle and mystery plays performed on an outdoor wooden stage.

Briefly:

1. The blue background in all frescoes is the “fondale,’ the large, undecorated curtain that hung in the rear of the outdoor wooden stage to block the view of the stage sets and the actors behind the actors. If it was the horizon, as we see it in the first fresco, the temple was built on Mount Everest.

2. In Birth of the Virgin we see TWO newborn babies, and Anne did not have twins. Because the spectators saw the scenes walking from right to left when there were no seats, the saw Anne reaching from the Virgin, then two ladies giving her the first bath.

3. If it was not the direction imposed on the spectators, why does Saint Peter cut the ear of Malchus before this soldier entered the Garden of Gethsemane with the other soldiers?

4. The Church loaned colorful vestments to the theater. Jesus was born poor, yet in the fresco Expulsion of the Merchants, he wears a “dalmatica,” a vestment with embroidered gold stripes around the neck, at the edge of the sleeves, and one that goes from his right shoulder to the waste.

5. Gitto designed the famous Bell Tower of the Florence Cathedral, yet he paints the steps we see in the fresco Presentation of the Virgin to the Temple so incredibly small in relation to the size of Anne that she could fall.

6. If it was not a stage set in Annunciation to Anne, wherein the world did the spectators see a house that has only one room.

The theater was theater in 1305.

In interested in reading the complete stud, email me

Ubaldo DiBenedetto, Ph.D.

Dear Mr. DiBenedetto,

I am training to be a docent at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.. I am fascinated by your research as I have been reading everything I can find to identify those who influenced Giotto.I have read that some think Cimabue trained him, but Giotto’s innovations surpassed him.

As an actress, I relish learning more about the Medieval theatre productions happening in Florence in the early 1300’s. I look forward to learning more from your generous offer to share your research.

With great appreciation,

Joanne Maylone