Suzanne Le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau, Jacques-Louis David, 1804. Oil on canvas, 23 2/4 x 19 1/2 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 97.PA.36

Jacques-Louis David was as political an artist as ever lived. He was a leader of the French Revolution, a prominent member of the radical Jacobin party, and a close friend of leader (and infamous tyrant) Maximilien Robespierre. He organized over-the-top propaganda festivals for France’s new republic. He even did jail time for his role in the Reign of Terror.

David’s revolutionary fervor was sincere. His portrait of Suzanne Le Peletier, painted in 1804, is a symbol of the sacrifices many French families made for the creation of the republic. Suzanne’s father, Michel Le Peletier, was a revolutionary who was murdered by a bodyguard after voting for Louis XVI’s execution. Suzanne became an instant celebrity after the assassination, transforming into France’s official “daughter of the state.”

Napoleon took interest in David after seeing a painting he completed in jail. Far from sinking into obscurity under France’s new ruler, David rose to exalted status as his First Painter. Ten years later, Napoleon fell and the monarchy returned to power—but David, who like Le Peletier had voted for the death of Louis XVI, was not only granted amnesty, but asked to become court painter yet again. He instead chose self-imposed exile in Brussels, spending his final years training young painters and living peacefully with his wife.

The Sisters Zénaïde and Charlotte Bonaparte, Jacques-Louis David, 1821

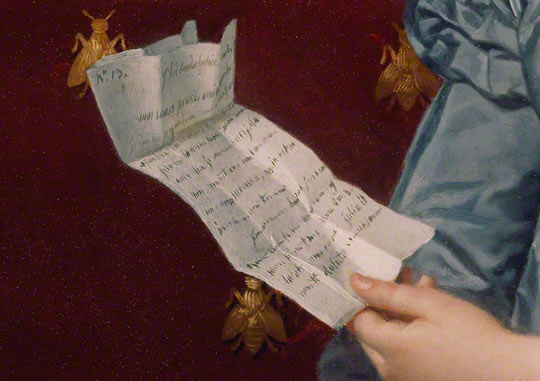

This portrait of Zénaïde and Charlotte Bonaparte—going on view Tuesday in the newly installed galleries for Neoclassical, Romantic, and Symbolist sculpture and decorative arts—is a testament to David’s close relationship with the Bonaparte family. Painted in Brussels in 1821, the year of Napoleon’s death and six years after the Bonaparte family fled France, the portrait shows Napoleon’s two nieces reading a letter from their father, Joseph Bonaparte, who was living in Philadelphia. Zénaïde holds her younger sister with a protective embrace, appearing candid and forthright. Charlotte, looking softer and more timid, glances at us with shy eyes. The creases and folds in the letter hint at the sadness caused by the family’s separation.

In his later work, David favored ancient Greek themes over the Roman subjects of his revolutionary days. Painted when he was nearly 70, The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis depicts the tale of Telemachus, a character in Homer’s Odyssey, who wants to remain on Calypso’s island with the nymph Eucharis. Though he longs to stay, Telemachus knows he must continue his quest for his father, Odysseus.

The Farewell of Telemachus and Eucharis, Jacques-Louis David, 1818

David contrasts the man’s cool logic with the woman’s irrepressible emotion by portraying Eucharis in profile, hands thrown around Telemachus, who looks out at the viewer in calm resignation.

David died in 1825, just six years after Géricault awed the Salon with his Raft of the Medusa, signaling the rise of Romanticism and the wane of Neoclassicism. Story goes that he was struck by a carriage while walking home from the theater. Not a very glamorous end for the onetime pageant-master of the French Revolution, but perhaps fitting for a man who retained to the last his belief in liberté, égalité, fraternité.

Comments on this post are now closed.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks