Centennial Hall by night, contemporary photograph. Photo: Stanislaw Klimek, 2004. Museum of Architecture Wroclaw

The Getty Foundation’s Keeping It Modern grants support conservation of significant 20th-century architecture around the world, and many of the sites have layered histories. Take Centennial Hall—Hala Stulecia in Polish—in Wroclaw, Poland. Constructed in the former German city of Breslau between 1911 and 1913, it was built to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the four-day Battle of Leipzig in 1813. In this “Battle of Nations,” as it is also known, coalition forces from Austria, Germany, Russia, and Sweden won a decisive victory over Napoleon Bonaparte and his occupying armies.

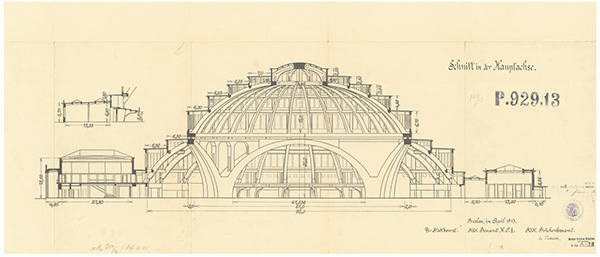

Open elevation drawing of Centennial Hall by Max Berg. 1913. Museum of Architecture Wroclaw

Designed by German architect Max Berg (1870–1947), Centennial Hall is equal in scale to the military event it memorializes. Berg designed a quatrefoil building with an open floorplan flanked by massive, pre-stressed concrete arches that support an elegant, low-sloping concrete dome composed of five stacked tiers of windows. The largest reinforced concrete structure in the world, it featured a freestanding dome with a span of no less than 73 yards (67 meters)—a new record at the time. Overall the design heralded a new era in architecture, an approach that relies on simple lines, minimal ornamentation, and raw unfinished interior concrete surfaces.

Centennial Hall, interior. Photo: Stanislaw Klimek, 2005. Museum of Architecture Wroclaw

It is not an exaggeration to state that Centennial Hall is on a par with Brunelleschi’s cupola of the Florence Duomo (Santa Maria del Fiore)—a building that, in the early Renaissance, embodied the pinnacle of building technology. Centennial Hall is equally groundbreaking as an engineering feat and for its extensive use of reinforced cast concrete, an innovative building approach that was still highly experimental when work began in August 1911. In fact, the building served as a key reference for subsequent reinforced concrete structures and was inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage list in 2006.

A Marvel of Engineering

The current Keeping It Modern grant, awarded by the Getty Foundation in 2014, is supporting the development of a Conservation Management Plan to preserve this engineering marvel into the future. One of the key areas of research needed for the plan focused on its use of concrete, as well as its construction.

Opening ceremony of the Centennial Exhibition, May 1913. University Library in Wroclaw, Graphics Collection

Berg believed buildings should be designed from the inside out, reflecting a growing practice embraced by his contemporaries, including Petrus Berlage (1856–1934), who said: “the purpose of architecture is to create space, and it should thus proceed from space.” Berg certainly succeeding in creating space: the usable floor area is a whopping 45,000 square feet. No small accomplishment for a space without a single support column.

For a building of this size and mass, you might expect to have seen a landscape filled with enormous cranes busily hoisting structural components to their destined locations. But this was not the case. So how, then, did they achieve the construction of this remarkable building in less than two years? The contractors ingeniously placed a large tower at the center of the building site and strategically used two smaller towers operating on a circular track. Strong steel cables connected the towers, which were capable of hoisting loads of well over 5,000 pounds Game of Thrones fans in particular may enjoy this short animated video of Centennial Hall’s construction:

Two purpose-built cement factories made all the concrete needed on-site, and local Silesian granite was ground to gravel nearby and used as aggregate. The wood used for concrete casting was prepared at a sawmill especially established for the project. Each element of the building was engineered to the highest standards of the day, resulting in a structure with a load-bearing capacity six times greater than originally calculated.

By contemporary measure, this would most likely make Centennial Hall one of the safest buildings on the planet. However, workers were unfamiliar with concrete and were afraid to remove the wooden casings after the material had set, fearing the entire structure might collapse. Only after Max Berg himself started pulling out some of the planks with the help of a volunteer did the construction crew muster enough courage to begin removing the coverings.

Centennial Hall, interior under construction, Fall 1912. University Library in Wroclaw, Graphics Collection

Seating over 6,000, Centennial Hall has functioned as a venue for cultural and social gatherings for over a hundred years. Beginning with the Centennial Exhibition, it has hosted numerous expositions, political rallies, sports tournaments, and dignitaries, such as Pope John Paul II and the Dalai Lama. Today it is home to a regular slate of international meetings and theatrical and musical performances. Centennial Hall has had to accommodate many uses—especially now that Wroclaw is the 2016 Cultural Capital of Europe, with a fully packed events schedule.

Centennial Hall, interior, European Congress of Culture, 2011. Photo: Kamil Czaja Wroclawskie Przedsiebiorstwo Hala Ludowa sp. z o.o.

Preparation of the Conservation Management Plan

The building was restored in 2005, but has lacked an overarching strategy for its future care and maintenance. In response, under the guidance of the director of Wroclaw’s Museum of Architecture, Dr. Jerzy Ilkosz, a team of architecture and engineering experts have used the Getty’s support to prepare a Conservation Management Plan (CMP) that provides a detailed roadmap for the site’s long-term care and conservation.

For more than a year, the team has undertaken extensive research in local and international libraries and archives that uncovered a cache of historic documents, including original construction contracts, building materials lists, stenograph records of committee meetings, and numerous photographs, design sketches, and drawings. In tandem, architects and engineers analyzed and tested the building’s materials and structural performance; conservators and scientists conducted detailed color studies; and a landscape architect examined and mapped the site’s grounds.

An example of data capture used to prepare the 3D model of Centennial Hall. Photo: Jerzy Jasienko

Every nook and cranny was measured with the latest laser technology to form a base 3D model. Finite Element Method (FEM) helped capture the structure’s complex geometry, and this FEM data was used to develop a Building Information Model (BIM), which are used in many Keeping It Modern projects to define site conditions and monitor change over time. This helps building stewards respond as needed to shifts that might threaten a structure’s integrity or design.

The Centennial Hall team has combined all of its historic and technical data with long-term monitoring system software, and now has a tool that continuously acquires data from strategically placed sensors located throughout the building’s interior and exterior. This means key technical information from the present—or any moment in the past—can be retrieved and analyzed, and cyclical maintenance schedules updated, as needed.

With all this information in hand—combined with an advanced understanding of Centennial Hall’s architectural significance and innovative structural engineering, the building’s CMP, and its conservation policies—the building will now have custodians fully prepared to preserve it for the next hundred years. And, thanks to the team’s hard work, it will function at optimum performance.

If you plan on traveling to Wroclaw to visit Centennial Hall, you might schedule it around May 1, 2016, when the city square will be filled with more than 7,344 guitarists set to break the world record for playing Jimi Hendrix’s “Hey Joe” in unison. If Centennial Hall’s windows are still in place after this event, we will have irrefutable proof that it is one of the best-engineered buildings in the world.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.