Visitors gather to examine Herakleides’ shroud paintings. Photo: Niraali Pandiri

“Take a look at Herakleides. What do you see?”

My tour group gathers around Herakleides, the Romano-Egyptian mummy in the Getty Museum’s collection, taking their first good peek at the 2,000-year-old body beneath the glass case. The motifs of ancient Egyptian gods and goddesses that adorn his shroud speak to a religion, mythology, and culture that date to 5,000 B.C., one marked by legends so intricate that five-year-olds and museum professionals alike still puzzle over them. But, as I’ve discovered this summer, interpreting and sharing these stories with visitors brings Herakleides’ world a little closer to our own.

I’m a second-year college student working as a facilitator for “Mummy Magic,” the Getty Villa’s ArtQuest! summer family program. Any family can drop by ArtQuest on Saturdays and Sundays from 11:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. through Labor Day Monday to learn about ancient Egyptian religion and the magic used to resurrect mummies in that belief system. As a facilitator, I lead family-centered tours of Herakleides and teach a short lesson on Egyptian burial magic combined with a make-your-own-mummy activity.

Sculpting a mummy model from aluminum foil and plaster wrap. Photo: Niraali Pandiri

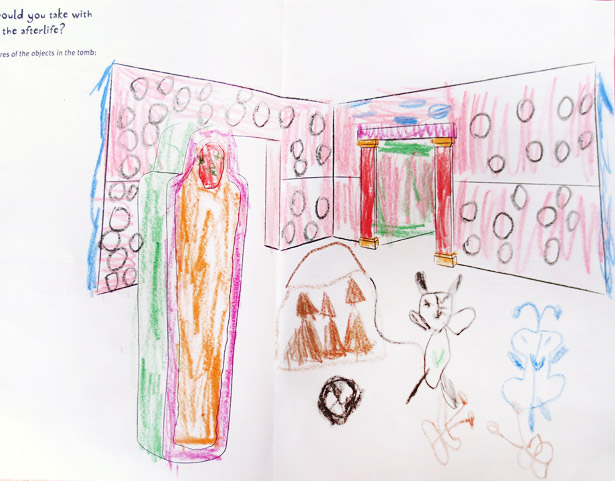

Visitors can also decorate a picture of their own mummy tomb with the special possessions they would bring to the afterlife, as shown in the example below. You can see more of their contributions, along with ancient works of art relating to the afterlife, on our Who’s Your Mummy? Pinterest board.

Visitor Zooey Richmond sketched what she would take with her to the afterlife: her soccer ball, chocolate, a butterfly, and her pet mouse.

“Mummy Magic” is both educational and creative, for it combines the discovery of the methods and magic of mummification with the interactive experience of sculpting, wrapping, and painting a mummy. Indeed, working at ArtQuest this summer has inspired me to engage with ancient Egyptian culture creatively and to share this process of discovery with visitors of all ages.

After seeing Herakleides, visitors paint and add magical symbols to their mummy models. Photo: Niraali Pandiri

I’ve discovered an incredible amount about the richness of ancient Egyptian culture. The legends reveal ancient Egyptians’ hopes for the afterlife and their painstaking devotion to the ceremonies, rituals, and magical practices that defined their world. Mummification affirmed the value of the deceased’s life: the priests who prepared and wrapped the body preserved it with care so that the deceased could use it fruitfully in the next world. The practice also reaffirmed their faith in the magical powers of gods and goddesses. From the feather of Ma’at—the feather against which each person’s heart would be weighed in the afterlife—to the magically healing Eye of Horus, each symbol inscribed upon Herakleides’ casket has its own special story that fits within the larger narrative of ancient Egyptian mythology.

Details of the symbols painted on the linen wrapper of the Mummy of Herakleides: Isis (center) and one of two eyes of Horus (inset)

What I love most about ArtQuest, though, is the energy, curiosity, and imagination that visitors bring to the tour and activities. When I retell the story of the Weighing of the Heart, one of the key stories from the Book of the Dead, I feel transported to the chamber of the underworld that houses the magical golden scales and the feather of Ma’at. I can imagine the hope and anxiety each person faced as they prepared a mummy for judgment, ready for him or her to either rejoice in the Field of Reeds or be devoured by Ammit, a fearsome lion-crocodile-hippo hybrid.

Papyrus from the Book of the Dead of Ani showing the Weighing of the Heart (center). From Thebes, Egypt; 19th Dynasty, around 1275 B.C. Pigment on papyrus, 44.5 x 30.7 cm. The British Museum, London. © Trustees of the British Museum

Mummy of Herakleides, Romano-Egyptian, made in Egypt, about A.D. 150. Linen, pigment, and gold (body); tempera on wood (portrait), 69 x 17 5/16 x 13 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 91.AP.6

Like most stories of ancient Egyptian mythology, the Weighing of the Heart is one that both adults and smaller children can enjoy—it’s got suspense, an adventurous journey, and scary monsters, but it also reflects the hopes, fears, and ideals central to the ancient Egyptians’ belief system. And as I show families the magical amulets used to protect the mummy’s heart through these tests of character, their challenging questions and thoughtful ideas inspire me to view the story with new eyes.

It’s amazing to watch visitors discover Herakleides for themselves—whether they’re gripped by the mythology or grossed out by the actual process of making a mummy (which includes pulling out the brain, piece by shriveled piece, through the nose). Each visitor is surprised, inspired or delighted by something different. Kids have asked me, eyes wide as they stared at the shroud, “Is the mummy really still in there?” Because it’s almost unbelievable that a man who lived, breathed, ate, slept, and died thousands of years ago has so much of his story still intact for us to discover and share. It makes the mysteries surrounding his identity, such as his red-pigmented shroud and the little ibis bird mummified into his wrappings, even more captivating. When his body is preserved for us to explore today, we can’t help but wonder what each clue means and who, exactly, Herakleides was in his own time.

Comments on this post are now closed.