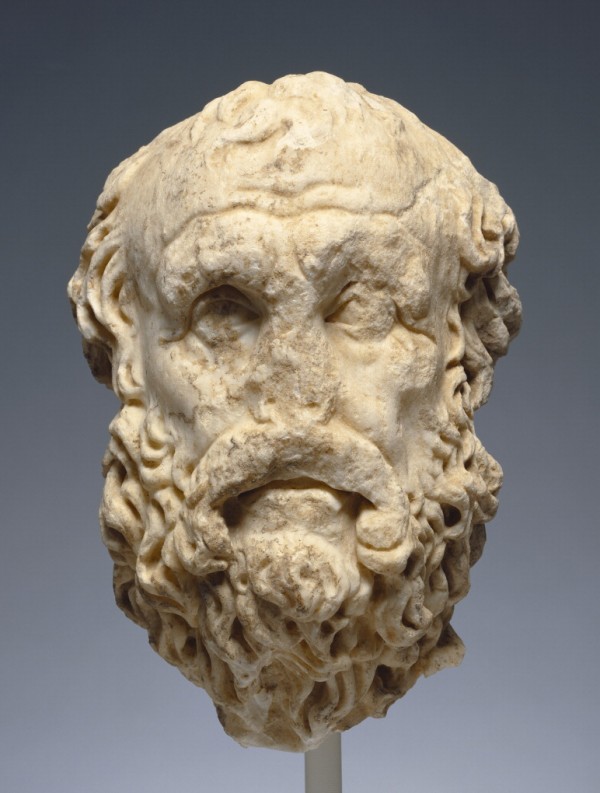

Portrait Head of a Balding Man, Roman, about A.D. 240. Marble, 10 1/16 in. high. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 85.AA.112

I don’t consider myself bald, I’m just taller than my hair.

—Seneca the Younger (not really)

Much like Donald Trump, men and women in ancient Rome were very conscious of their coiffures. Roman attitudes toward hair (or lack thereof) differed immensely depending on age, sex, and social status, and was known to be a source of anguish for both Roman men and women. So although there’s no evidence that Seneca actually said the zinger above, as an ancient Roman he definitely should have.

As a classics student, my interests in the ancient world lie less in wars and dates, and more in recognizably human themes, such as vanity, the natural inclination to poke fun at your elders, and the timeless misery of hair.

Male Baldness and Its Discontents

A signifier of wisdom, gravitas (dignity), and severitas (sternness), male pattern baldness was considered an ideal characteristic of an upstanding Roman citizen, and was used to convey venerability on portraits of philosophers.

Portrait Head of Diogenes, Roman, A.D. late 100s. Marble, 13 in. high. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 73.AA.131

Head of an Old Man, Roman, 25 B.C.–A.D. 10. Marble, 13 15/16 in. high. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 96.AA.39 Image: Bruce White Photography

Especially in the Republican period, from 509 to 27 B.C., Roman portrait patrons often chose to be presented with glisteningly bald heads, large noses, and extra wrinkles to express the years they had devoted to the Roman state.

But despite the air of patriotism associated with baldness, it would seem that a receding hairline outside the realm of portraiture wasn’t nearly as desirable. The famously bald (and somewhat defeatist) Emperor Domitian lost many a night’s sleep over his hair loss (Emperors, they’re just like us!):

Be assured that nothing is more pleasing,

but nothing shorter-lived.

—Emperor Domitian, on having hair. From Suetonius, Life of Domitian, 18

The horror of baldness also appears in poetry:

Ugly are hornless bulls, a field without grass is an eyesore, So is a tree without leaves, so is a head without hair.

—Ovid, Ars Amatoria, 3.223–254

Men would dye their hair and have it curled in an attempt to avoid greying or thinning, and to preserve any youthful, Jon Hamm-like features. As an example of the unfortunate propensities of real hair, see the wispy, greying locks of this stumbling and aged follower of Dionysos, tired after a long night of drinking.

Fresco Fragment Depicting an Old Silenos with Kantharos and Thyrsos (detail), Roman, A.D. 1–100. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 83.AG.222.2

Hair dyes were often extracted from bark or walnut shells, carbon, or straight ash—materials also used to dye textiles. Because both balding and going grey were associated with deteriorating health and generally losing your marbles, hair dye proved a popular practice amongst Roman men.

But dyeing one’s hair also served as a prime opportunity for ridicule, and any man attempting to disguise a receding hairline was in for a relentless mocking from poets (and, presumably, sassy Roman teenagers):

On your bald pate no wig you use.

You draw hairs on, with no excuse.

At least no barber needs to trim it.

You can erase it in a minute.

—Martial, Epigrams, 6.57Your hairs are carefully disposed

Lest your bald pate should be disclosed.

But winds lift them in wavy drifts,

Moved in a blur of constant shifts.

How can you have so little hair,

Yet have it show up everywhere?

—Martial, Epigrams, 10.83

So to be bald, or not to be? You can’t win.

Women’s Hairy Agonies

Just like for men, hair was a major determinant of both respectability and physical attractiveness for women. Not unlike Kim Kardashian’s beauty routine, hair was the first step in any Roman woman’s prep, notes author Seneca.

Roman braid-weaving from J. Stephens, “Ancient Roman Hairdressing: On (hair)pins and needles,” Journal of Roman Archaeology 21 (2008): 111–133

All hair endeavors for the wealthy Roman woman would have fallen under the domain of an ornatrix, or beauty expert specifically skilled at cutting and dyeing hair—depicted, ironically, as short-haired throughout Greek and Roman art as suited her slave status. (See the slave’s short hairstyle compared to her mistress’s well-tended-to locks on this grave marker.)

Such female hairdressers were also responsible for styling hair with dangerous hot tools such as the calamistrum (a cylindrical, fired curling iron), and for sewing in locks of false hair, most often in the form of braids (pictured).

But female vanity, even more than male, was ceaselessly mocked:

A lock of her well-pampered hair flopped free.

Her glass made her this horrid error see.

Against her hairdresser she smashed the glass,

Her baldness should for smoothest mirror pass!

—Martial, Epigrams, 2.66Your teeth and hair you plainly buy.

Too bad you cannot buy an eye.

—Martial, Epigrams, 12.23

A popular hairstyle that utilized hair extensions can be seen in these portraits of Julia Titi and an anonymous Roman woman. In both of these women’s hairstyles, their extravagant curls are piled high and woven together in a pre-Marie-Antionette updo.

Portrait Head of Julia Titi, Roman, about A.D. 90. Marble with polychromy, 13 in. high. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 58.AA.1

Bust of a Flavian Woman, Roman, late 1st century. Marble, 26 ¾ in. high. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 73.AA.13

Sometimes a more modest front view hid the extreme updo’s reverse, which required long artificial braids and exceptional styling technique on the part of the ornatrix. Business in the front, party in the back!

Business in the front. Portrait Bust of a Woman, Roman, A.D. 150–160. Marble, 26 9/16 in. high. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 83.AA.44

Party in the back.

Here you can see a similar look reconstructed by historical hair rockstar Janet Stephens:

For those who couldn’t afford their own personal beauty team, there were local barbers and hairdressers. The barbers would do more than simply give you a trim; they would also clean and cut your fingernails, tend to calluses, and even remove warts and moles. No woman would have cut her own hair unless she were in dire financial circumstances. Many plebeians also wouldn’t have owned proper combs, which provided a good excuse to go to the barber for a slice of town gossip.

Aside from the hair on their heads, Roman women often opted for the naked mole rat look, bidding vale (farewell) to all bodily hair. For hair removal, many would pluck, use pumice stones, or wax off their hair using a paste made of resin. But like the toupeed men discussed earlier, older women who shaved were ridiculed, as this was seen as preparation for sex. Seems you can’t win either, lassies.

After having their hair prepped, Roman women would put on the final touches: shave their eyebrows (who needs ‘em?), lace their eyelids with soot, powder their faces with lead (for that dreamy/poisonous white complexion), and rouge their cheeks with rust and/or wine.

Unlike portraits of their husbands and brothers, portraits of Roman women were far more concerned with representing the latest ideas of fashion and beauty than the subject’s actual features. Like men, however, Roman women also faced conflicting attitudes towards their outward appearance. Criticized for being both too made-up, and not made-up enough, the struggle for Romans of both sexes was all too real. Alas, we can’t all be Farrah Fawcett.

Still interested? See further reading below.

Further Reading

- How did they do that ‘do?, The Washington Post

- Ancient Roman Beauties and Their Makeup Bag, Italy Magazine

- Hair Dye and Wigs in Ancient Rome, Italianthro blog

- On Pins and Needles: Stylist Turns Ancient Hairdo Debate on Its Head, The Wall Street Journal

- The Caryatid Hairstyling Project, Marbles Reunited

Text of this post © Madeline Warner. All rights reserved.

The article was quite interesting on hair styles.

wha a clever person you are! The”combovers” evidently go back centuries…..Jane

I loved this video. Great to see a woman’s viewpoint of Roman society. I’m going to Rome in a few weeks. I’m also visiting Pompeii, a lifelong dream. You made ancient Rome come to life for me. A fascinating slice of daily life. I got a chance to go to the Chrysler glass museum in Virginia, It had beautiful fragile perfume and makeup jars made of glass over 2000 years ago. I have no idea how those tiny delicate objects made it through the centuries. Thank you for your research. Carpe diem.

I wonder if the Roman women kept hair “rats”. I can remember my grandmother who was born in 1885 keeping a special dish by her dresser. When she combed out her waist long hair she would roll it up like a “bat” of wool and save it in a hair keeper in order to give volume to her Gibson girl hair-do. Of course, my other grandma was a flapper and wacked all her hair off into a short crimped bob. Reminds me also of the beautiful hair braids I see on modern Afro-American women.

interesting article on hair styles.