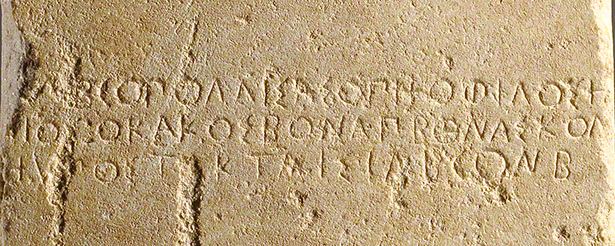

Gravestone of Pollis, Greek, made in Megara, about 480 B.C. Marble, 60 1/4 in. high. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 90.AA.129

The intimate association between being remembered and risking one’s life on the battlefield lies at the heart of Homer’s Iliad. The preeminent warrior Achilles famously chose to die young in battle and be forever honored, and this heroic code is well expressed when the Lycian warrior Sarpedon embarks on an assault against the Greeks. He rouses his comrade Glaukos with these words:

[T]he Lycians at home distinguish you and me with marks of honor, the best seats at the banquet, the first cut of the joint and never-empty cups…. Does this not oblige us now to take our places in the frontline and fling ourselves into the fire of battle? Only that way can we make our Lycian men say this about us: “Surely no inglorious men are these, our kings, who rule in Lycia, and they eat fat sheep and drink first-rate honey-sweet wine. But their might too is noble, since they fight in the frontline.” —Iliad 12, 310–321

To fight in battle and risk one’s life is to be talked about, commemorated, celebrated. For Veterans Day, it’s appropriate therefore to look closely at an object in our collection that stands as a lasting physical record to the power of memory. It’s a gravestone, for a man by the name of Pollis, and is a rare instance among ancient Greek funerary monuments in that it preserves both an image and a text. Even at first glance, it’s clear how Pollis is to be remembered. He stands, tensed, as if in formation in the phalanx, his shield on his shoulder and spear ready for an underarm thrust. This is a brave and unflinching warrior, ready and willing to fight in the frontline.

Looking more closely, the inscription written above the image tells us even more. First of all, his name—Pollis, the beloved son of Asopichos. It also tells us how he died: the Greek word st[i]ktaisin has been interpreted as meaning “by the wounds of the tattooers”—shorthand for the Thracians, who were notorious amongst the Greeks for their tattoos. We know that the Thracians fought with the Persians against the Greeks during the Persian Wars, and it was presumably in fighting them and defending Greece that Pollis lost his life. But perhaps the most striking term lies at the heart of the text—o kakos. Pollis did not die “like a coward.” Two and a half thousand years after his death, the record of Pollis’s bravery lives on.

Comments on this post are now closed.