Prints and drawings scholars, including Paper Project fellows, Ian Hicks (right) and Klazina Botke (left), study a drawing by artist Jacopo da Pontormo (1494-1557) from the collection of the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen. Photo: Albert Elen

Prints and drawings often make up large portions of museum collections. These works on paper help curators understand an artist’s process, or provide clues to new connections among artists and their works. At the same time, they are some of the most challenging works to care for and study. They damage easily, must be kept in the dark after going on display, and require specialized knowledge across regions and time periods.

Today, as many museums experience shrinking staffs, understanding these objects often falls to one or two curators responsible for thousands of diverse works of art. As senior curators in the field retire, their positions are going unfilled. This has created a growing gap in training and support for the next generation.

The Getty Foundation’s initiative, The Paper Project, works to ensure that this specialized knowledge is preserved and expanded, providing new opportunities for curators to share and advocate for the collections they oversee.

Foundation-funded research and curatorial fellows might work with visitors in study rooms to bring out prints and drawings temporarily from storage for up-close examination, develop exhibitions, make new discoveries about the origins of artworks, and share this information through digital catalogues.

We caught up with three of the nine current Getty-funded fellows to find out what they’ve learned.

Building Networks and a Collaborative Community

Ian Hicks (left) examines artworks from the collection of the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen during a convening of prints and drawings scholars in The Hague. Photo: Aad Hoogendoorn, Rotterdam

For Ian Hicks, the ability to collaborate with new colleagues during his fellowship at the University of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum has been transformative. His main project is cataloguing the museum’s significant collection of early modern Italian drawings by celebrated artists, from Leonardo da Vinci to Tiepolo. “This project is a group effort,” said Hicks. “It is work that demands a strong network to bring in the expertise of others.”

Hicks’s fellowship also took him to a convening hosted by Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in The Hague, where more than a dozen international prints and drawings scholars discussed the challenges they face, in particular the vast number of unattributed or anonymous pieces in museum collections.

At the end of the meeting, participants were able to request works of their choice to be pulled from the Boijmans’ storage vaults. “I was drawn by a sudden sense of excitement at one of the study tables, where several experts were actively discussing the authorship of a drawing attributed to Giovanni Battista Naldini,” said Hicks.

Following their conversation and close study of the drawing, the scholars came to a surprising new realization: the work was actually by Naldini’s teacher, the famed Florentine Mannerist Jacopo da Pontormo. New research on the drawing is now being carried out by another Paper Project fellow working at the Boijmans, Klazina Botke.

Jacopo da Pontormo, Study for the Angel of the Annunciation, n.d., red chalk, pricked for transfer, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam (former Koenigs collection). Photo: Studio Tromp, Rotterdam

For Hicks, joining the curators as they proposed different interpretations was an incomparable experience, one that reinforced the importance of developing strong professional networks. “It was a fantastic opportunity to look shoulder-to-shoulder with seasoned experts and get a sense of how they approach things,” he said. “I really don’t think there’s anything that quite compares.”

Making New Discoveries with a Keen Eye

The attribution in The Hague relied on a deep knowledge of an artist’s style and hand, but this is only one method used by drawing experts to identify unknown works. Sometimes, the ability to synthesize knowledge across various art forms and media, such as painting, sculpture, and architecture, can lead to new discoveries.

Raffaello Vanni, The Royal Ancestors of the Virgin, 1653, lunette painting at the Chigi Chapel in the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo, oil on panel, CC-BY-SA-4.0

Raffaello Vanni, Compositional Study for the Prophets Saul and David, 1653, The British Museum, Photo: Grant Lewis

At the British Museum, research fellow Grant Lewis was working through an album of 370 unknown workshop drawings, when he noticed a unique triangular cut-out in one of the bound works. “That was the moment I thought, ah, I’ve seen this before,” said Lewis. He quickly made the connection between the album drawing and the Chigi Chapel in Rome, which includes pyramidal tombs in front of painted scenes.

Grant Lewis examines a drawing in the study room of the British Museum. Image courtesy Grant Lewis

Confirming his hunch, Lewis established that several figures in the album drawings matched paintings in the chapel by the 17th-century Italian artist Raffaello Vanni. Lewis has since determined that half of the album drawings correspond to known works produced by Vanni and his workshop. Paint drops and smears on some of the sheets even match the colors used in the artist’s finished works. “You really get a sense of the artist holding the drawing in one hand as he painted with the other,” Lewis said.

Recognizing that these smudges and a missing segment of paper were signs of the drawings’ use and application, Lewis was able to identify the object’s past and transform the work into an important piece of historical evidence.

Ensuring Access and Serving the Collection

At the Musée des Arts décoratifs (MAD) in Paris, curatorial fellow Sarah Catala is working to more deeply engage audiences with works on paper. The MAD’s collection has more than 200,000 drawings, ranging from Old Master works to designs for the decorative arts, fashion, and jewelry. Yet staffing shortages over the last two decades have made it difficult to access these treasures.

To bring renewed attention to the breadth and range of materials in the MAD’s holdings, Catala is working with the curator on a large-scale exhibition of 500 prints and drawings.

Sarah Catala (left) leads a visiting tour group at the Cabinet des dessins at the Musée des Arts décoratifs during her Getty-funded fellowship. Photo: Markus Schilder © 2019 J. Paul Getty Trust

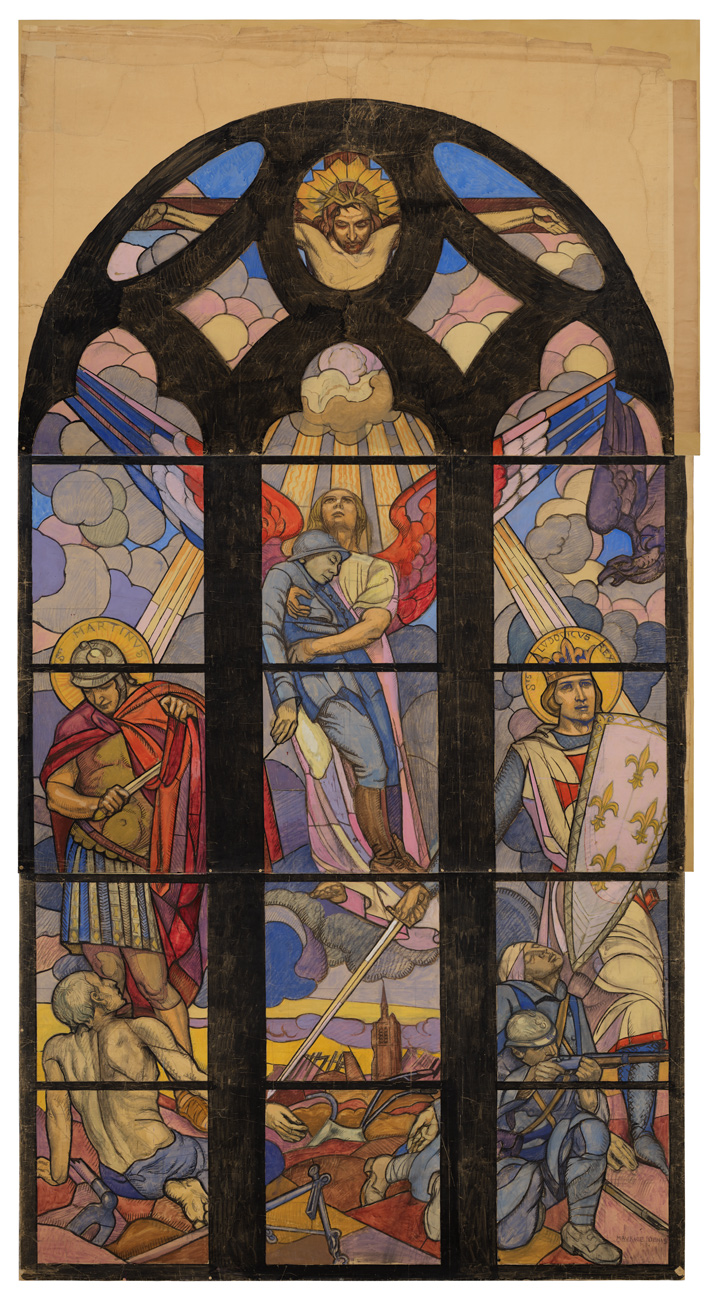

Like Hicks and Lewis, Catala has had the chance to take part in new discoveries. She was present when one of the department’s temporary trainees found an eight-foot-long drawing signed by French artist Maurice Denis that had been concealed for years on a top shelf. Together they determined that it was a design for a stained glass window at the chapelle Saint-Louis of Sainte-Macre church in Fère-en-Tardenois.

The chapel where the window was originally displayed was heavily damaged during World War II but, remarkably, both the window and drawing have survived. “It was not my discovery, but just being present for this moment was significant in itself,” said Catala.

Maurice Denis, preparatory drawing for one of the figures in Aux morts pour la France, c. 1924, Gift of Paul Denis, Photo: Sarah Catala, courtesy Musée des Arts décoratifs, Paris

Maurice Denis, Aux morts pour la France, 1924, Charcoal, gouache on woven paper, Acc. no. RI 2019.33.1., Gift of Étienne Moreau-Nélaton, 1925. Photo: Sarah Catala, courtesy Musée des Arts décoratifs, Paris

As the fellowships continue for all of the scholars participating in The Paper Project, more discoveries await. To get updates on their work and the results of other professionals supported with Getty grants, you can follow the Foundation on Facebook and Twitter.

These insights and educational emails are incredibly energizing and are an unexpected delight.

The wonderful monographs Give me a deeper appreciation of a curator’s process while enabling me to enjoy the presented arts in a new way.

Thank you for bringing a wonderful experience to my home while we are unable to experience the joy of visiting museums in person.