The Getty Research Institute’s Art and Architecture Thesaurus (AAT) is focused on the terminology of the fine arts, but it is also equipped to encompass all of human knowledge and experience. Part of the Getty Vocabularies, the AAT continuously expands, growing through submissions from a variety of contributors, including the Getty’s own archivists. While processing the Juan Fassio Pataphysique Collection, one such archivist encountered the term pataphysics and suggested adding it to the thesaurus.

The collection, compiled by the Argentine Juan Esteban Fassio, contains materials related to a society known as the Collège de ‘Pataphysique, which was founded in Paris in 1948. It included figures “so prominent in their professions as to reveal the omnipresence of ‘Pataphysics in the innermost offices and conference rooms of our civilization,” as Roger Shattuck wrote in his introduction to a 1960 issue of the Evergreen Review devoted to the pataphysical. Man Ray, Max Ernst, Jean Dubuffet, Umberto Eco, and yes, the Marx Brothers were all associates of the Collège.

What Is Pataphysics?

Pataphysics is a concept attributed to the French writer Alfred Jarry (1873–1907), though the term was originally coined by Jarry and his schoolmates in Rennes in the late 19th century as somewhat of a joke. He described it enigmatically as “the science of imaginary solutions.”

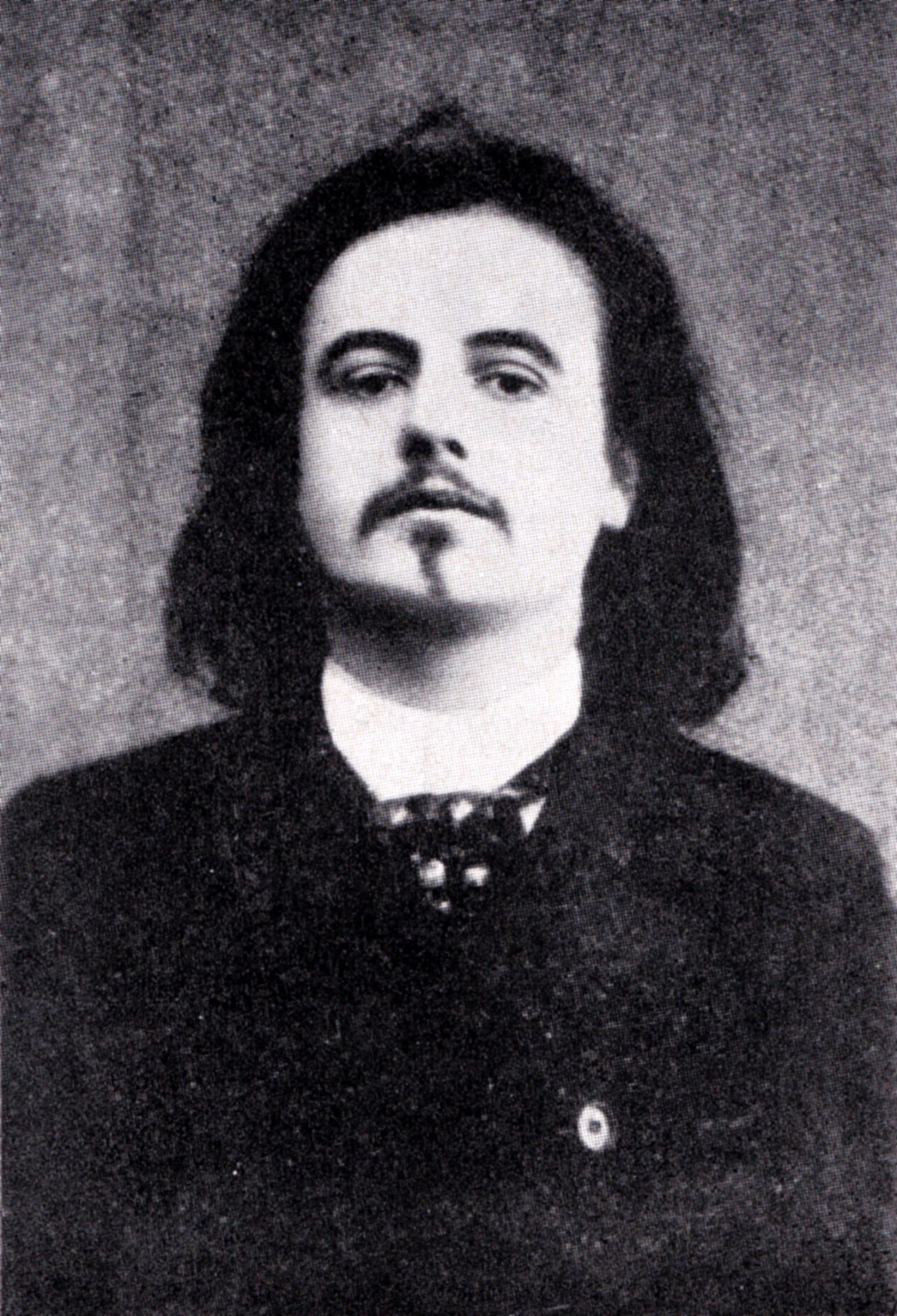

Photograph of Alfred Jarry, attributed to the studio of Nadar, taken around the time of the original performance of Ubu Roi. The Getty Research Institute

In the context of editing a controlled vocabulary such as the AAT, the form of the word proves particularly interesting. Jarry added a preceding apostrophe to the original French word pataphysique “to avoid an easy pun.”

This apostrophe is commonly dropped, and the Library of Congress prefers omitting the vexing punctuation. Jarry himself failed to use it routinely. The Italian artist Enrico Baj has pointed out that the apostrophe is used to distinguish “voluntary ‘pataphysics,” which is practiced by pataphysicians, from “involuntary ‘pataphysics,” which is practiced by everyone else.

The word has been translated into multiple languages, spawning whole fields of inquiry, literary practice, and conceptual art-making worldwide. Describing pataphysics briefly is a challenge, as even acknowledged pataphysicians do not adhere to any unified definition outside of Jarry’s original.

According to Alistair Brotchie, a regent of the Collège, the science “is practiced by all men, without their knowing it” and “is the very substance of the world.” (Brotchie, 1995). In a Collège de ‘Pataphysique circular, pataphysics is described as “the vastest and most profound of Sciences, that which indeed contains all the others within itself whether they want it or not.”

Pataphysics renders all opposites as equal, and through wordplay pushes rational processes to irrational extremes. Pataphysicians have claimed that the science is at work in the unrealized inventions of Leonardo da Vinci. The painter Asger Jorn considered pataphysics “a religion in the making.”

Who Was Alfred Jarry?

If not a religion, Jarry certainly spawned the cult of pataphysics when his novel Exploits and Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician was published posthumously in 1911. The book introduced pataphysics to the world and granted Jarry disciples, though his initial celebrity status came as a playwright.

Jarry’s play Ubu Roi, also inspired by his schoolboy pranks, was first performed in Paris by the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre in 1896, with sets, masks, and costumes created by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Pierre Bonnard, among others. The first word of the play—a distortion of a French word for ordure, “Merdre!”—caused a fifteen-minute riot and made Jarry famous. Thereafter, the writer lived a life of his own invention, under the influence of alcohol and the laws of pataphysics.

There are countless anecdotes of Jarry’s eccentricities. He carried a loaded pistol everywhere, and wasn’t shy about firing it in mixed company. He kept live owls as pets. He refused to drink water, claiming that it was a toxic solvent, so he lived on absinthe and ether instead. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he died of tuberculous meningitis at the age of thirty-four.

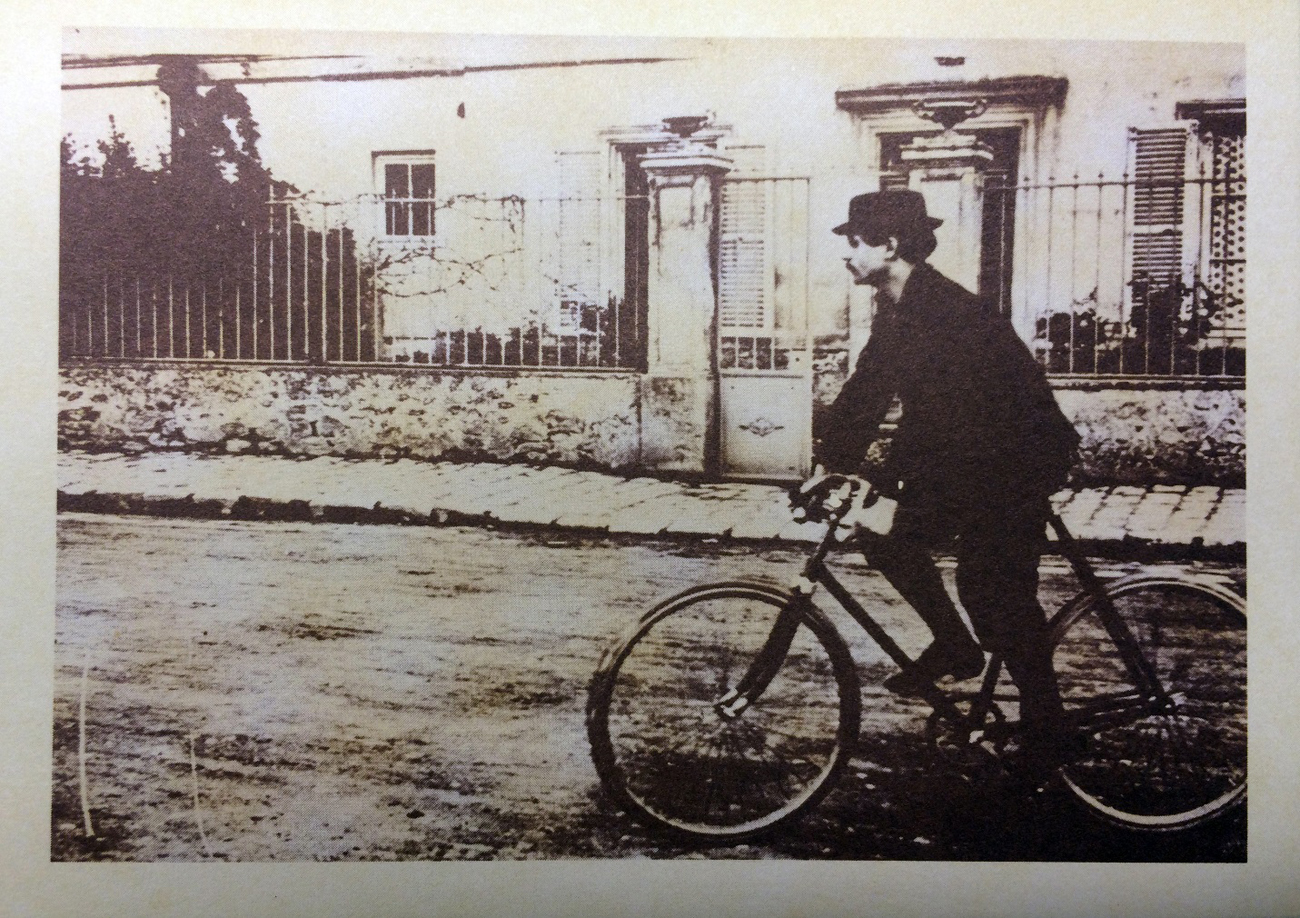

Alfred Jarry riding his Clement Luxe, 1898, one of a set of postcards created by a member of the Collège de ‘Pataphysique. The Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.30

But Jarry was also a scholar of the classics and well read in the sciences. He was a dedicated athlete who traversed vast distances on a racing bicycle. He practiced fencing and fished for his own food in the Seine. Jarry was a lifelong friend to a patient few, including the painter Henri Rousseau, whose work he championed. Beneath the legend lies a compelling and complicated personality.

Jarry co-founded a marionette theater, the Théâtre des pantins (1896–98), with the painter Pierre Bonnard, composer Claude Terrasse, and poet Franc-Nohain. Jarry produced lithographs for the covers of the three published albums of the Répertoire des pantins, containing sheet music by Terrasse. Illustrated here is La Chanson du décervelage (Disembraining Song), 1898. The Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.30

Pataphysics in the Archive

The Getty Research Institute’s collections contain many resources on pataphysics. In addition to the Juan Fassio Pataphysique Collection, the Harald Szeemann papers contain extensive materials on the College de ‘Pataphysique, as Szeemann was a member. Elsewhere are editions of the elaborate art magazine Jarry cofounded with Remy de Gourmont called L’Ymagier, which include texts by Jarry (under his own name and under the pseudonym Alain Jans) on Catholic iconography and “Monstres.”

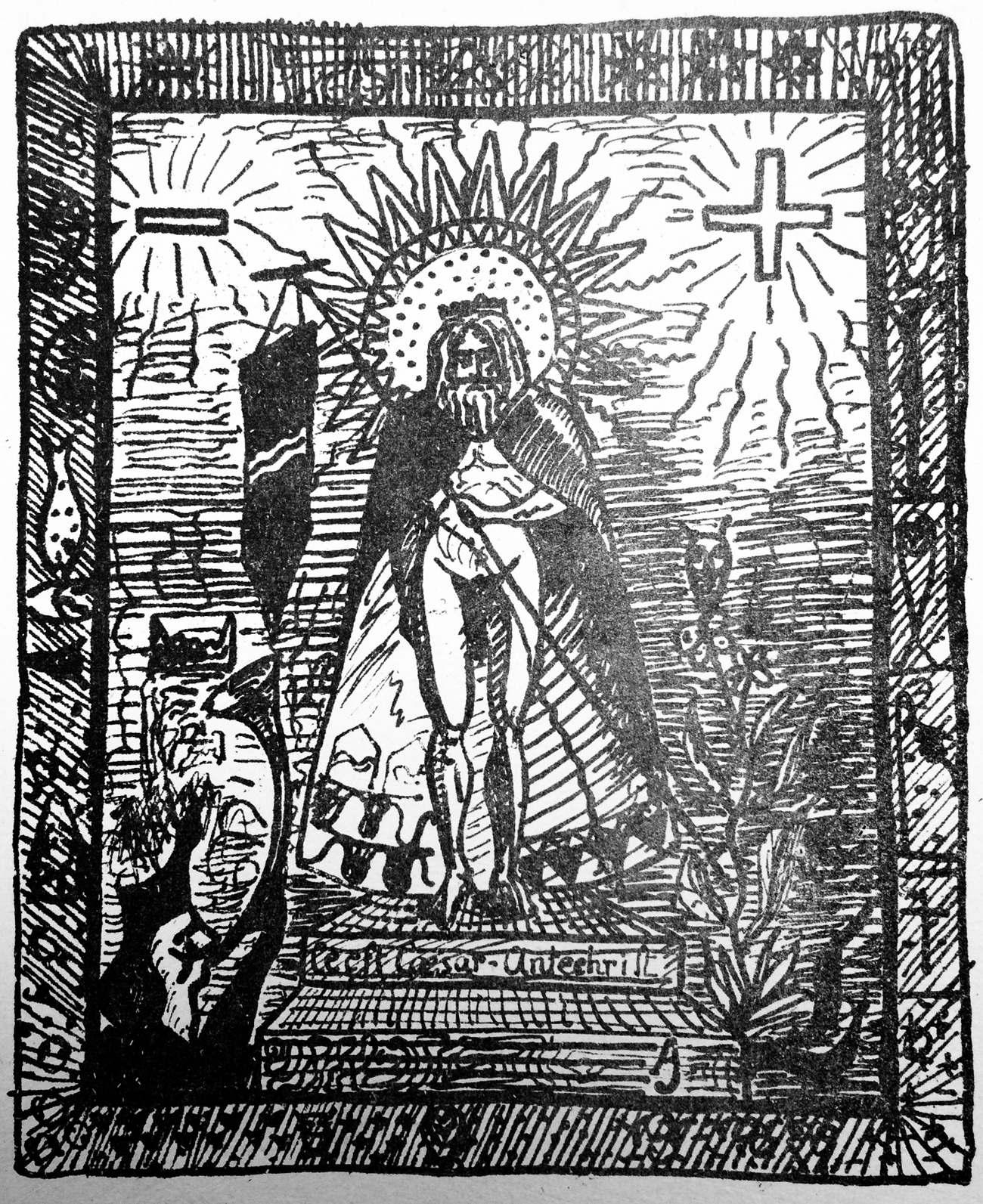

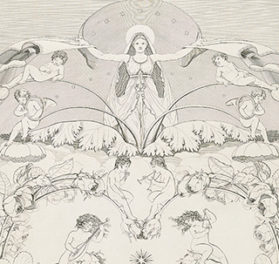

César-Antéchrist, Alfred Jarry. Lithograph. Published in L’Ymagier, no.2 (1895). The Getty Research Institute, 90-S404

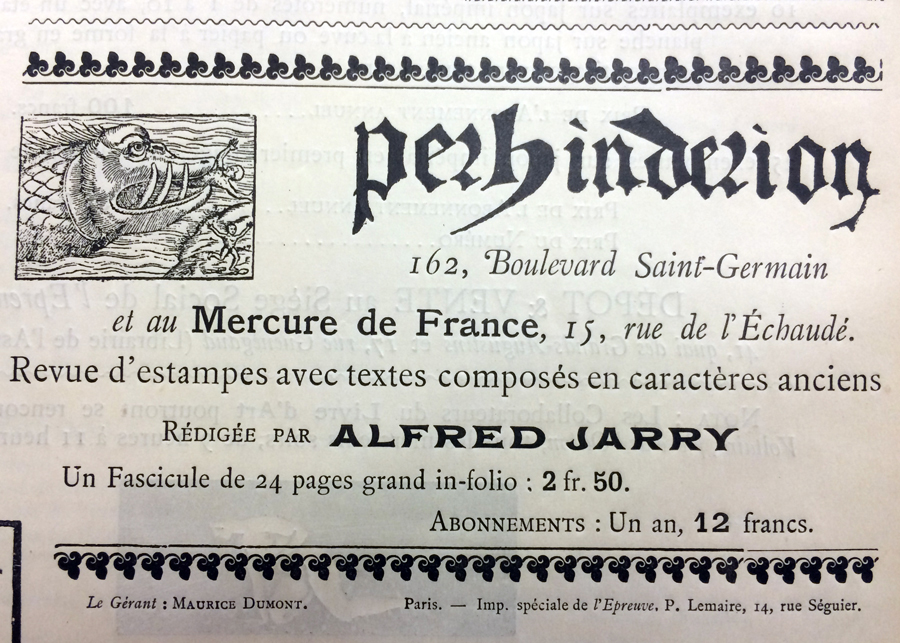

An advertisement for Jarry’s second elaborate art magazine Perhinderion. It appeared on the back page of the review Le Livre d’Art, no.1 (1896), in which Ubu Roi was first published. Jarry spent a significant amount of his own money to have special type cast for the project. The Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.30

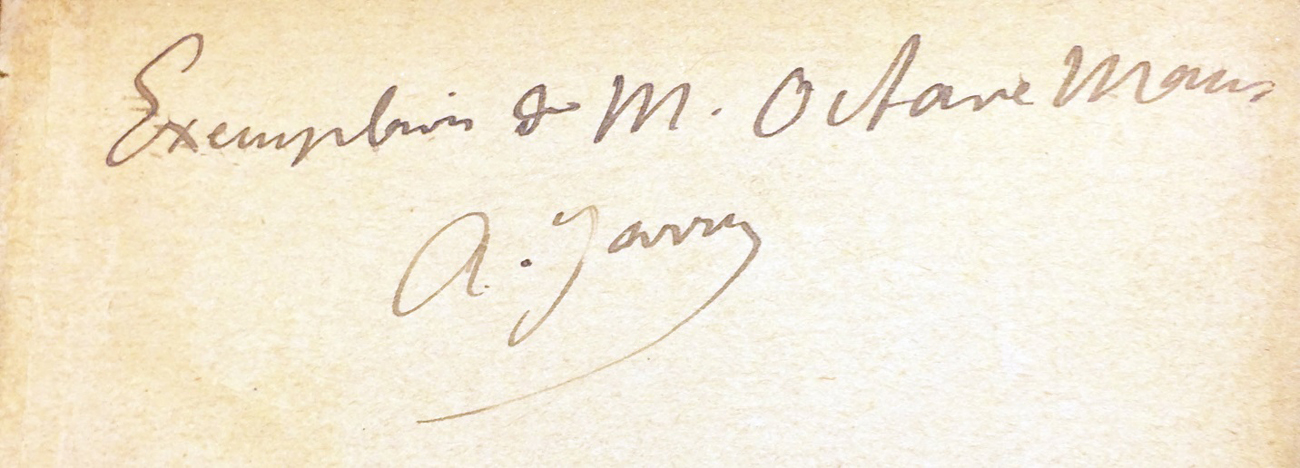

The Getty Research Institute also holds many books by or about Jarry. These include a presentation copy of Ubu Roi inscribed by Jarry for Octave Maus, a Belgian critic and founder of the weekly L’Art Moderne.

Inscription in the first edition of Ubu Roi (Paris: Éditions du Mercure de France, 1896). The Getty Research Institute, 89-B17734

Mapping Connections

There are explicit connections between Jarry’s work and persona and the protagonists of early 20th-century avant-gardes. With linked data, these intersections can be made clear. Using the Union List of Artist Names (ULAN), for example, we can tie Jarry to all the figures in arts and literature with whom he is associated and specify the types of relationships.

His influence spirals out from his immediate contemporaries: Pablo Picasso collected Jarry’s manuscripts (and inherited his pistol), and Filippo Tomasso Marinetti, the architect of Futurism, commissioned Jarry to write articles for his pre-Futurist magazine, Poesia.

Marcel Duchamp’s entire oeuvre can be seen as illustrating aspects of the pataphysical. His readymade sculpture Bicycle Wheel (1913) might even be interpreted as a monument to Jarry the obsessive bicycle rider. Jarry’s work was read at one of the first Dada soirées at the Cabaret Voltaire in 1916, and André Breton, in his Anthologie de l’humour noir of 1940, credited the French writer with erasing the barrier between art and life.

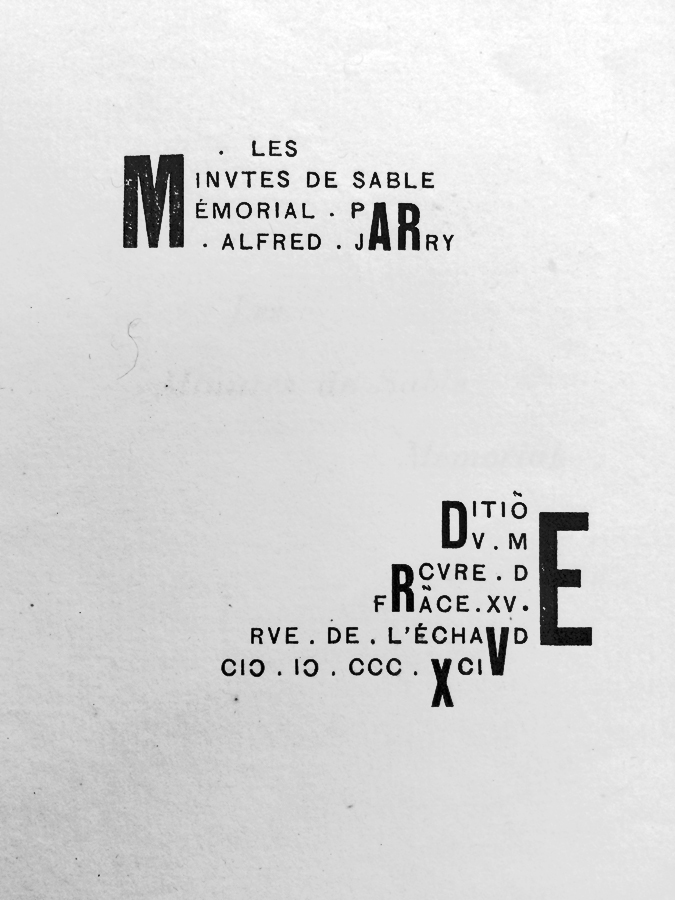

Title page of Jarry’s Les Minutes de sable memorial showing a type layout that prefigures later Dadaist typographic experiments. The Getty Research Institute, 1371-412

Resources at the Getty Research Institute illustrate the expanding and prolonged gyre of connections that begin with a single individual such as Jarry. Metadata and controlled vocabularies provide a map of these connections that otherwise lie latent in printed matter and its digital surrogates. They also enable us to trace a concept like pataphysics in the formation of modernity. Through metadata and Linked Open Data, we can connect these strands on a global scale, and in the process, separate rumor and anecdote from the equally astonishing facts that precede them.

Comments on this post are now closed.