The artist collaborative known as A BEE takes a unique approach that defies categorization. Their “tapestorial sculptures” take an age-old craft and put a modern spin on it.

The members of A BEE chose their name in a nod to the “quilting bee,” which, to them, summons an image of women working together in a community and sharing knowledge. This collective identity allows them to keep the focus on their art—manipulating original silk-screened imagery into a 21st-century blend of tapestry and sculpture.

We met the artists when they shared their work to the #GettyInspired gallery, and were curious to know more about what they do and why.

Kim Sadler: Tell me about yourselves and your art backgrounds. How did you meet? When and how did you start collaborating?

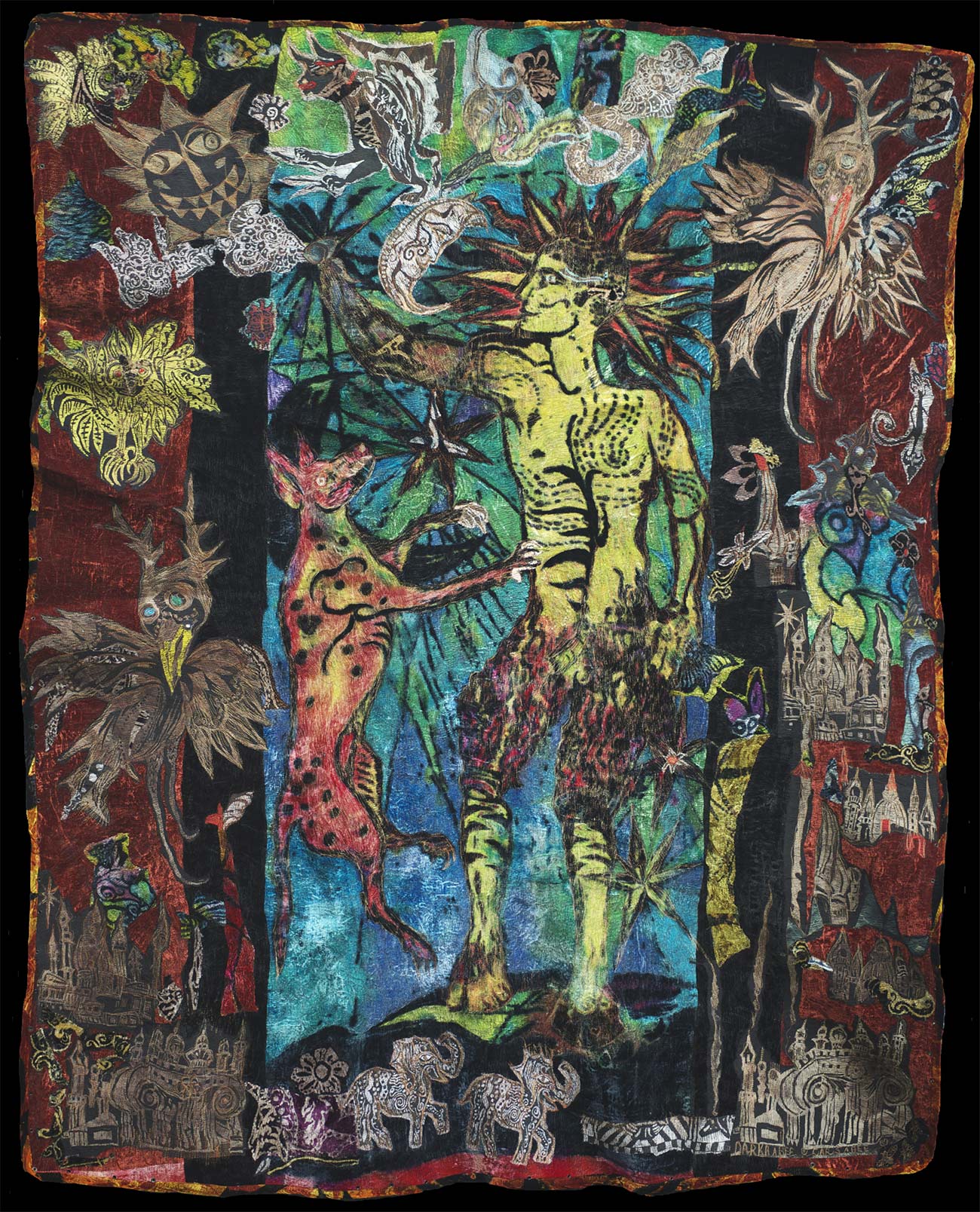

A BEE with Hercules panels. Image courtesy of A BEE. All rights reserved

A BEE: A BEE is made up of Cars Houseman and Darka Novoselic, friends who found similar and deep interest in literature, classic and contemporary arts, and creative arts such as dance, fashion and pop-culture.

We have no art background—we started collaborating organically with creative endeavors such as making dance costumes for friends and silk-screened T-shirts, which caught the eye of a Japanese company and grew from there. We ended up with a multitude of sample silk-screens which couldn’t be repeated as shirts—thus, our library of original print imagery had begun.

We wanted a way to utilize and preserve the prints we made as samples. Both of us love museums, and major museums like the Met and the Getty had enormous tapestries rife with detail…and inspiration. We decided to create larger screens with life-sized characters, flora, and fauna. As the screens grew, the pieces themselves have grown. We are working out how these epic-sized pieces work in harmony together.

Tapestry can be seen as an old-fashioned craft—how did tapestry capture your attention? How are your creations similar to and different from classical tapestry?

As we started to create larger screens with larger and life-sized images, we wanted them to interact with each other, to become allegorical in their feel. As the pieces were being stitched together they seemed to take on a carpet-like appearance.

From our early days of showing the smaller-sized pieces in juried craft shows, we wanted language that steered away from the “Q” word [quilting], and we started to research the terminology and vocabulary of tapestry. What a fantastic journey that led to! We found we had more in common with the world of tapestries: the cartoons, the detailed stitching, the complexities and nuances of fibers, the coloring, and the narratives. Tapestry has become our thesis, our personal study in language and composition. The sheer beauty, versatility, malleability, and presence!

However, we are doing it our way. We are making it up as we go, even coining our own terminology, “tapestorial sculpture,” as our pieces are not woven on a loom. They read woven: They have a sculptural organic variation to them, and they are dual sided, with the bulk, pull, and buckling of a tapestry. They are luxurious and the silk has a heady, intoxicating smell. They are heavily embroidered, full of haptic detail from each stitch up to the print story, and lastly they have the potential to be combined with other pieces and linked to form snaky labyrinths or vertical mobiles, for example.

Boy, A BEE. Image courtesy of A BEE. All rights reserved

The sculpture aspect in “tapestorial sculpture” is that we intend to build environments that draw the viewer in on a journey, to mingle and interact with the characters in our pieces—to create a feeling of our tapestries coming alive. We are taking an age-old craft and making it new. To the tapestorial works, we also print and compose our cartoons on silk yardage, to flesh out the environment as if walking straight into our enchanted world as the fluid cloth ripples and dances with motion.

What inspires you? In general, and also specifically at the Getty?

Obviously, the tapestries on view at museums and the tomes written by Thomas P. Campbell and other scholars help with terminology and history. The exhibition Woven Gold: Tapestries of Louis XIV at the Getty was extremely inspiring, as it is always visually pleasing to see each one up close and study techniques, language, composition, and scale. We have poured through the Getty publication of French Tapestries and Textiles as well as Woven Gold by Charissa Bremer-David.

We’re also inspired by the decorative arts and by mythology and symbolism throughout the Museum. There is a particular Etruscan vase at the Getty Villa from 525 B.C. that depicts images of the labors of Hercules that has inspired a new series based on that iconography.

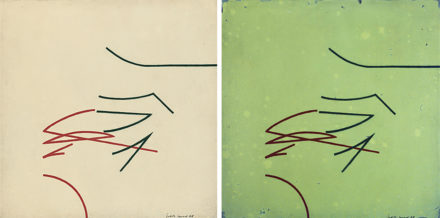

We are also inspired by our own images, the endless possibilities and infinite combinations. We tend to mirror our characters—one-off silk-screens each have a chiral essence, the same but not the same. As two women collaborators who work together in close proximity, we have a chiral quality as well.

A new “tapestorial” piece by A BEE on the work table. Image courtesy of A BEE. All rights reserved

Take us through your creative process.

Our creative process is complex. Perhaps that’s why we have the need to collaborate. The physical demand of working with large-scale pieces, the labor and time involved in making silk-screens, filling mesh with beeswax, actual printing, mixing dyes, pigments and the alchemy processes, choosing fabrics, threads, composition and cartooning, layering, pinning, and sewing is extensive. Printing is hard, messy, physical work.

Many of the screens we use are very large and require two bodies to ensure a crisp, even outcome. We print, cut, and compose on 25-foot work tables. Sometimes the elements fit perfectly, but often they need to be painstakingly adjusted until the right feel is achieved. There is a shared concern regarding how the print imagery is to be kept current in style—while we try on specific ideas and glean subject matter from the past, it’s of utmost importance not to literally translate. We invest much thought and discussion in creating our own vernacular.

The technique and interpretation of the final product when we call it “done” supersedes preconceived ideas of the traditional. We are finding our own way, making it up as we go along—both in printing and stitch techniques. We are making decorative art with the intent of large visual potential and artistic reception. We call it “tapestorial.”

What’s next for you and your work?

We often appear in the photographs of our work in order to show scale. Because of the size and detail of the work we find ourselves handicapped by the limitations of our cameras—especially as we connect the murals together, making them more epic in scale. The pieces are malleable and meant to be linked. As of yet, our only exhibitions have been flat on walls—we would like the opportunity to execute the “sculpture” side of tapestorial sculpture—to develop and transform a space that engages and beguiles the public.

See all posts in this series »

A BEE: Cars Houseman + Darka Novoselic

Web: abeearewe.com

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/abeearewe/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/ABEEarewe

Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/abeearewe/videos

GETTYinspired: http://blogs.getty.edu/inspired/a-bee/

Your work is mesmerizing!! It’s so original. As someone who works with fabric in a much smaller format (dolls), I’m totally impressed!!