The differentness of ancient Egypt, Herodotus’s “alien land full of wonders,” was the theme of a recent scholarly workshop at the Getty Villa bringing together Getty curators and visiting scholars who are pursuing research on cultural and artistic exchange among ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome.

What made ancient Egypt so different? Protected by water and desert on all four sides and shielded from invasions that might have exposed it to new languages, cultures, and political systems, Egypt was “a navel-gazing place,” in the words of workshop moderator and UCLA Egyptologist Kara Cooney. Even during lengthy periods when the country was ruled by foreigners—Libyans, Nubians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, Romans—Egyptian culture had a remarkable power to absorb and egyptianize the newcomers, leaving its conservative core of language, religion, and pharaonic rule intact.

Workshop participants included Egyptologists, classicists, archaeologists, and art historians, and interdisciplinarity was a theme of the day. Traditionally, Egyptologists “have been a closed society,” said Martina Minas-Nerpel, but “disciplines talking together, and bringing study of imagery, language, and sites together, is very important.” Participants agreed on the need to adopt shared terminology; currently, scholars from different disciplines sometimes fail to understand one another because they use different words, and mean very different things with the same words—in particular, the words “Egyptian” and “Egyptianizing.”

“We use different terminology because we come from different fields,” explained Richard Veymiers, but “we need to be careful, and not assume that one of our disciplines knows better than another.”

Key questions raised throughout the day included:

- How did ancient Egyptians think about cultures other than their own? Was there ever a clear understanding of the boundaries of “Egyptian,” even in ancient times?

- For what purposes did the Greeks and Romans adapt Egyptian gods and symbols?

- How can the original context of ancient societies be separated out from the mirrors of culture and historiography?

- To what extent should scholars attempt to understand, or even adopt, the ancients’ own frames of reference?

- How can today’s rationalist scholars grasp the complexity of the ancient world?

Papers addressed these questions through a variety of focused case studies; I’ve summarized each below and added links to the most relevant books and web resources by the authors.

- How Powerful Were Egypt’s Queens?

- How Did the Romans Remember Egypt?

- What Do Romano-Egyptian Mummy Portraits Mean?

- How Did Egyptians Encounter the Gods?

- What Did Egyptian Artifacts Mean to the Romans?

- How Can We Untangle Historical Sources to Find the Past?

- How Multiethnic Was Ancient Egypt?

How Powerful Were Egypt’s Queens?

Ptolemaic queens in the Egyptian temples: A “holy family of women” crossing intercultural boundaries?

Martina Minas-Nerpel, Swansea University, UK

Temple of Hathor at Dendera, rear wall: Ptolemy XV Kaisarion and Cleopatra VII conducting offerings to the gods of Dendera. Photo: Martina Minas-Nerpel

Historians have long underrated the importance of Egyptian queens, Martina Minas-Nerpel argued, mischaracterizing them as insignificant appendages to kings, inherently inferior because of their gender.

While the king was the unquestioned political and religious figurehead of Egypt, queens had a complex role with more power than is usually recognized. Wife and mother, the Egyptian queen also had divine status, serving as the earthly embodiment of Hathor and thus “a regenerative medium for the king in his role as representative of the sun god on earth.”

Focusing on the Ptolemaic dynasty, when Egypt was under Hellenistic rule, Minas-Nerpel described several exceptional queens, including Arsinoe II, the first Ptolemaic queen to be depicted in iconography while still living, and Cleopatra VII, a ruler of political genius. And yet, Minas-Nerpel noted, Cleopatra is remembered to this day often only as a decadent “femme fatale”—an example of the gulf between the ancient Egyptian understanding and the conception of the Classical authors, as well as between ancient and modern concepts of gender and power—and a reminder of the complex roles of the ancient world that are “difficult for us to understand today.”

Read more: Ägyptische Königinnen vom Neuen Reich bis in die islamische Zeit. Beiträge zur Konferenz in der Kulturabteilung der Botschaft der Arabischen Republik Ägypten in Berlin am 19.01.2013, Verlag Patrick Brose, 2013.

How Did the Romans Remember Egypt?

Memories of Egypt: How gardens within ancient Roman temples celebrated a fresh take on Egyptian religion

Martin Bommas, University of Birmingham, UK

How did the Romans understand Egypt? Egyptian art and architecture dotted Rome starting in the first century BCE, and Egyptian religious cults were widespread in the Roman Empire. But this was more spectacle than scholarship, Martin Bommas argued.

Romans hardly ever traveled to Egypt; they didn’t read papyri, though one emperor liked to burn them for the smell. But like many cultures before and since, the Romans “never viewed their lack of detailed knowledge as a disadvantage.”

Instead, the Romans excelled at creating Egyptian-inspired pastiches combining exoticism with the scenery of past grandeur. Bommas described the Iseum Campense (“Isis of the Fields”), a massive temple in Rome dedicated to Isis, the Egyptian goddess of nature, good fortune, and prosperity. The rituals of Isis were restricted to paying initiates, but the temple’s vast pleasure gardens were well-known public attractions in Rome. Lush with exotic and native plants, wall paintings, obelisks, statues of recumbent lions, and live animals such as crocodiles and birds, the Iseum Campense may have been the world’s first cultural “theme park,” a place of memory celebrating a culture long gone by.

Read more: Cultural Memory and Identity in Ancient Societies, Continuum, 2011.

What Do Romano-Egyptian Mummy Portraits Mean?

Gods and mortals in Romano-Egyptian portraiture

Mary Louise Hart, J. Paul Getty Museum

Mummy Portrait of a Man, mid-3rd century A.D., attributed to the Brooklyn Painter. Tempera on wood, 13 3/8 × 9 13/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 79.AP.142. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Painted in vivid encaustic and tempera on wood panels, mummy portraits of Roman Egypt are extraordinary documents of ancient men, women, and children that were wrapped into their mummies as part of rituals around death and the afterlife. Characterized by emotional intensity and immediacy, these portraits show a range of ages, classes, genders, and castes.

The ultimate function of these portraits, said Mary Louise Hart, is “to recognize the culture and socio-economic status of those who commissioned them.” But who were these people, and what did these portraits mean to them? While several panels preserve the names of the deceased, most were removed from their mummies during excavations, making fuller context impossible to reconstruct. Hart talked about an exhibition she is planning that will bring many of these objects together, along with framed panels of gods, funerary shrouds, cartonnages, plaster portraits, and other objects used to stage what is termed the “theater of death.”

Research on Romano-Egyptian portraits by Hart and collaborators (see Svoboda, below) also seeks to address open questions, including: Are these stylized representations or genuine portraits of individuals? Were the paintings made at the time of death, or before? How were painters trained and how were workshops organized? To what extent can we determine the hand of single artists?

Technical Research on Ancient Panel Paintings through the APPEAR Project

Marie Svoboda, J. Paul Getty Museum

Conservator Marie Svoboda described a project she is leading to compile comprehensive technical, scientific, and historic information on Romano-Egyptian portraits from 28 collections into a searchable database. The APPEAR project (Ancient Panel Paintings: Examination, Analysis and Research) brings together conservators, art historians, Egyptologists, artists, and material and imaging scientists to share expertise in specialties such as conservation imaging, art history, and pigment, textile, and wood analysis.

The APPEAR database already has 225 partial and complete entries, representing a quarter of all known mummy portraits in museum collections. Data span multiple aspects including material identification, panel shape, surface details, and marks found on the reverse. At a symposium planned for 2018 at the Getty Villa, participating scholars and scientists will present first findings from the project, drawing on data that will make rigorous cross-collection analysis possible for the first time, providing new information about these objects. “This work shows how collaboration can help unlock the secrets of the past,” Svoboda said.

Read more: Herakleides: A Mummy Portrait from Roman Egypt, Getty Publications, 2010; introduction to the APPEAR project, web resource.

How Did Egyptians Encounter the Gods?

Neighborhood gods: Interacting with divine images in the houses and shrines of Greco-Roman Egypt

Bethany L. Simpson, Getty Research Institute

Simpson in the Cairo Museum, delighted to discover rare wall-painting fragments from Karanis, the site of her research

Bethany L. Simpson examined the domestic architecture of Karanis (modern Kom Aushim), Egypt, to understand how its ancient residents would have seen and interacted with images of the divine.

The temples of Karanis were rather plain, yet the houses were highly decorated with religious iconography, suggesting the importance of private devotion. Domestic structures included cultic areas with built-in shrines that were originally molded and decorated. Painted panel fragments suggest other places that religious imagery would have appeared: a fragmentary wood panel with the eagle of the apotheosis that once hung in a domestic kitchen, and a wall painting of Horus once installed in a granary.

Simpson has newly reconstructed the layout of House 5046, a multi-story home with a large room on the ground floor ornamented with painted gods and shrines. We do not know what kinds of gods were worshipped in such shrines, but it is clear that such spaces would clearly have been the gathering place and religious center of a dwelling.

Simpson addressed the so-called “Karanis Pantheon,” wall paintings of gods found in House 4020. The sparse existing research on these paintings, Simpson commented, focuses on their iconography and style, not their use and meaning in context—suggesting the value of bringing an archaeological as well as an art historical perspective to examining such images.

Read more: Neighborhood Networks: Social and Spatial Organization of Domestic Architecture in Greco-Roman Karanis, Egypt, PhD dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, 2015; Aegaron: Ancient Eyptian Architecture Online, web resource.

What Did Egyptian Artifacts Mean to the Romans?

Egyptian collectibles in Roman houses

Stephanie Pearson, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

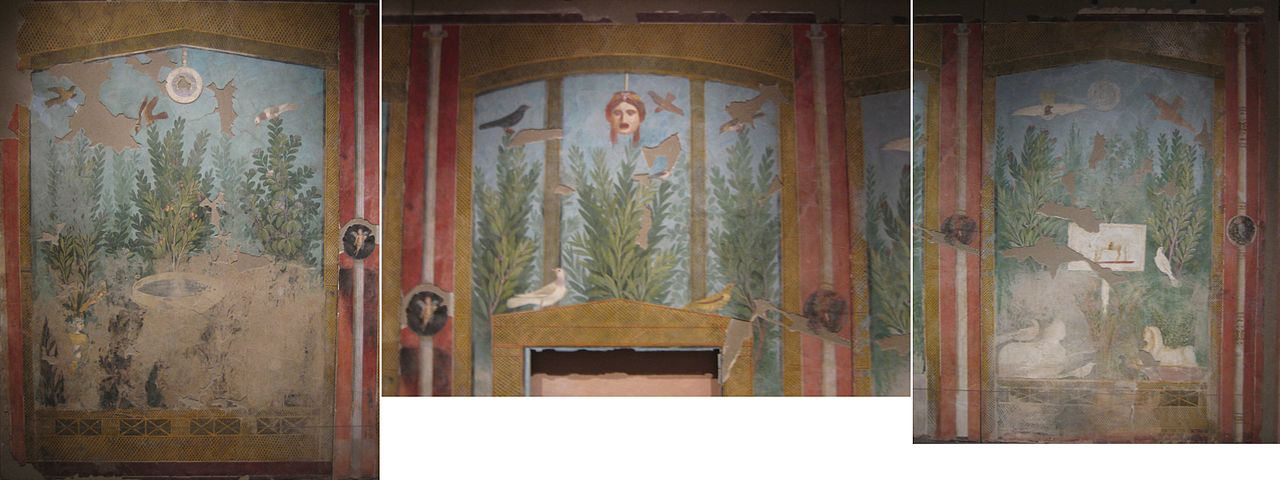

Wall painting from the House of the Golden Bracelet in Pompeii showing, at far right, a depiction of a marble sphinx. Image: Wikimedia Commons

For centuries after the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BCE, Egyptian imagery became prevalent in Roman art and architecture, with Egyptian obelisks and sculpture dotting the landscape.

Historically, said Stephanie Pearson, there have been two main ways to interpret these objects: as religious symbols reflecting the Roman worship of Egyptian gods, and as political symbols reflecting the assertion of Roman imperial power. She offered a third interpretation, suggesting that Egyptian objects were also used for purely aesthetic, decorative ends. (Pearson made the intentionally provocative choice to collapse the distinction between the terms “Egyptian,” made in Egypt by Egyptians, and “Egyptianizing,” made in Rome in an Egyptian style, because, she noted, the Romans themselves didn’t make that distinction; “Aegyptiacus” was their single term for both.)

Egyptian motifs found on sculpture and wall paintings from private houses indicate that they were valued for their pleasing visual effect. Wall paintings in the House of Augustus, for example, show stylized crowns and an ornamented silver pitcher with a cobra-shaped handle. Perhaps large-scale Egyptian sculpture also served a primarily aesthetic function, Pearson suggested. The Gardens of Sallust showed the wide-ranging taste typical of the Roman collector, containing an Egyptian obelisk, several Egyptian sculptures such as a figure of Arsinoe, and Greek sculptures in an array of styles from Archaic to Hellenistic. Might the obelisk have served first and foremost as an artwork, an object of wonder, and not a symbol of imperial domination?

By considering context, Pearson suggested, we can achieve a more balanced understanding of the complex ways in which Romans used, viewed, and valued Egyptian objects.

Read more: Egyptian Airs: The Life of Luxury in Roman Wall Painting, PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 2015.

How Can We Untangle Historical Sources to Find the Past?

Images and manipulation: The unauthorized biography of a Sarapis relief

Richard Veymiers, Leiden University

The original marble relief as it appears today in a private collection, Rome. Image courtesy of Richard Veymiers

In the 1500s Italian antiquarian and restorer Pirro Ligorio saw a marble relief depicting a god in the form of a coiled snake and a fertility goddess. He published a drawing of this relief, along with its accompanying votive inscription, in his influential compilation Antichità romane. The same relief was published again and again in antiquarian projects over the course of the next two centuries, gaining and losing its inscription and elements of its iconography.

However, Pirro Ligorio did not work as a historian: he dabbled in epigraphic forgeries and valued creating images of “antique greatness” over recording the truth. The relief, said Richard Veymiers, never had an inscription at all: Ligorio invented it and modified its iconography by adorning the goddess with new attributes.

The relief, which Veymiers traced back to Rome, appears to illustrate Serapis in the guise of his transformation into the snake-god Agathos Daimon, one of the most frequent motifs on Alexandrian coinage. We don’t know what name the ancients gave to such images of Serapis, as divine composite forms may have been perceived in various ways depending on the circumstances. The goddess depicted next to him must be identified as the personification of the annona, the imperial service ensuring grain supply from Alexandria to Rome, which benefited from the protection of Serapis.

Using the relief as a case study of the complexity of untangling iconography and meaning even of extant objects, Veymiers warned about “the modern reflex to try to find one single interpretation” of the past. “In antiquity, things were more complex.”

Read more: Hileôs tôi phorounti. Sérapis sur les gemmes et les bijoux antiques, Académie Royale de Belgique, 2009; Bibliotheca Isiaca II–III, Éditions Ausonius, 2011–2014.

How Multiethnic Was Ancient Egypt?

Ethnicities in Hyksos Avaris: New results from Tell el-Dab‘a-research

Manfred Bietak, University of Vienna/Austrian Academy of Science

The Hyksos, of Near Eastern origin, ruled Egypt’s 15th dynasty. Bietak, director of Austrian Archaeological Institute in Cairo for over 40 years, presented findings from the site of Avaris (modern Tell el-Dab’a) under Hyksos rule.

A harbor town connected to the major trading centers of the Levant, Avaris in the Hyksos period was filled with migrants and residents of several ethnicities, though the main inhabitants were a population of Western Asiatics responsible for the Hyksos rule. Other ethnicities were Nubians, and the remainders of the original Egyptian population of the town.

Recent finds at the site include a cuneiform fragment showing that the Hyksos introduced Akkadian as a diplomatic language, and that they had long-distance diplomacy long before the New Kingdom. Elements of the material culture, such as temple designs, show similarities to cultures of the northern Levant; charred acorns from their altars suggest that oak trees (not native to Egypt, and sacred to the Canaanite goddess Asherah) were introduced for religious reasons. Nubian pottery and tombs with Near Eastern weaponry have also been found.

Later, in the New Kingdom (after 1530 BCE), after this Hyksos town was retaken by the Egyptian king Ahmose, Minoans were also present at Avaris, which we know from original Minoan wall paintings such as bull/leaping scenes and Minoan emblems in a Thuthmosid palace at the site. These paintings are devoid of hieroglyphs and Egyptian emblems, suggesting that they were created by and for resident Minoans. At this same time, representations of Minoan delegations appeared in tombs of Egyptian dignitaries in the necropolis of the capital in Upper Egypt at Thebes.

Bietak dispelled the misconception that ethnicity and identity were simpler in the ancient world than today. “In antiquity you had multi-ethnicities,” he said. “There was perhaps no town that was not populated by other people.”

Read more: Avaris, the Capital of the Hyksos. Recent Excavations at Tell el-Dab’a, British Museum Press, 1996; “The Egyptian Community at Avaris during the Hyksos Period,” Egypt and the Levant 26 (2016), 263–274; with N. Marinatos and C. Palyvou, Taureador Scenes in Tell el-Dab’a (Avaris) and Knossos, Vienna 2007. See also: The Hyksos Enigma, webpage from the Austrian Institute for Oriental and European Archaeology.

Comments on this post are now closed.