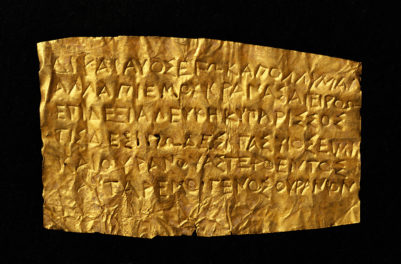

A Hedgehog (detail) in a bestiary, about 1270, unknown illuminator, possibly made in Thérouanne, France. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 7 1/2 × 5 5/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 3, fol. 79v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Meet 19 animals of the medieval bestiary in Book of Beasts, a blog series created by art history students at UCLA with guidance from professor Meredith Cohen and curator Larisa Grollemond. The posts complement the exhibition Book of Beasts at the Getty Center from May 14 to August 18, 2019. —Ed.

The hedgehog, a popular pet in England and worldwide on social media, is often thought to be harmless when compared to other beasts—especially those found in books from medieval Europe. After all, its only weapon, a coat of spines, is used strictly for defense.

But the adorable European hedgehog only vaguely resembles what we find in the medieval bestiary, a type of illuminated manuscript featuring stories and Christian lessons about animals. While today we might find these creatures cute, they had an incriminating and sinister reputation in medieval Europe.

Hedgehog as Thief

In bestiaries hedgehogs are depicted as pests, often stealing fruit such as grapes, figs, and apples. The hedgehog’s thieving tendencies were used to teach readers not to neglect their duties, because everyone wants to avoid finding the “fruit” of their hard work and devotion stolen.

Yet hedgehogs face many risks and sacrifices while foraging for food, not unlike parents struggling to support their children. The fruit that a hedgehog steals is meant to feed its young, underlining the importance of family within the medieval European tradition.

Barricaded against the Winds

Hedgehogs were often drawn similarly to pigs, which were perceived as insatiable, disgusting animals; in some books they also resemble the much larger porcupine. (Interesting side note: Hedgehogs have spines and porcupines have quills. While quills can lodge themselves easily into an attacker, spines stay put and can only be raised in defense.)

The hedgehog’s spines are used to protect it on all sides when it curls into a ball. This handy, self-enclosing defense mechanism was said to echo the garden critter’s ability to build a home that is similarly barricaded, but against the winds. According to Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder, whose animal tales influenced the medieval bestiary, hedgehogs “build two pathways for breathing…so that it may deflect the oncoming and threatening winds” from either the north or south. To medieval readers, this clever strategy indicated an innate, shrewd intelligence.

Hedgehogs (detail) in the Northumberland Bestiary, about 1250–60, unknown illuminator, made in England. Pen-and-ink drawings tinted with body color and translucent washes on parchment, 8 1/4 × 6 3/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 100, fol. 10. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

The Hedgehog and the Devil

The hedgehog’s defensive withdrawal is significant in the medieval bestiary because it is said to mimic the naive and stubborn nature of the wicked. Their inherently self-preserving acts are condemnable, according to St. Antony of Padua. He claimed that, like the most repulsive sinners of medieval Europe, the easily-frightened-and-furled hedgehogs possess five teeth, each of which represent different misguided justifications for their sins:

- Ignorance

- Chance

- Suggestion of the devil

- Frailty of own flesh

- Occasion given by neighbor

Hedgehogs actually possess more than five teeth, but this number may have been selected for its religious symbolism. Five is the number of Christ’s wounds on the cross: four nail wounds through both hands feet, and one spear wound in his side.

The oldest known bestiary text, the second-century-AD Physiologus, further describes the deeds of the hedgehog as a metaphor for allowing “that most wicked spirit”—temptation—“to climb up into your place….thus he [the devil] has deceived you with the barbs of death in order to divide your plunder among hostile powers.”

In bestiaries, therefore, hedgehogs were snaggle-toothed thieves who represented sinful looting of the goods produced by others’ honest productivity. This accusation likely reflected the general perception of foragers as nuisances. Hardly the image we have of the little critters today, right? But thief or not, the medieval hedgehog did what it took to parent, and to survive.

A Hedgehog in a bestiary, about 1270, unknown illuminator, possibly made in Thérouanne, France. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 7 1/2 × 5 5/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XV 3, fol. 79v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Further Reading

Clark, Wilene. The Second Family Bestiary: Commentary, Art, Text and Translation New York: Boydell & Brewer Ltd., 2006.

Text of this post © Melissa Pammit. All rights reserved.

See all posts in this series »

Comments on this post are now closed.