Saint Anne, better known to Angelenos as Santa Ana, teaches the Virgin to read in an illumination from a Book of Hours, about 1430–40, Master of Sir John Fastolf. Tempera colors, gold leaf, and ink on parchment, 4 3/4 x 3 5/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 5, fol. 45v

A dozen years or so ago, I set out to find connections between the stories of 100 saints and the streets that bear their names here in Los Angeles, a city which itself is named for a saint. (Nuestra Señora de los Angeles, Our Lady of the Angels–that is, the Virgin Mary).

One thing I was fairly certain of at the outset: Nearly all our saint-streets were, counterintuitively, named neither by Spanish explorers nor by Mexican settlers seeking to invoke a saint’s watchful blessings over their turf. No more than a handful of paths and trails carried the names of saints before the knolls and plains that became Los Angeles were declared American soil.

Rather, it was late-19th and early-20th-century Anglo developers and city boosters who—in seeking to bestow some amber-cast, Ramona-esque, Mission-style allure on otherwise anonymous stretches of pavement—gifted us these mostly Spanish titles.

But, as a believer in unintended consequences, this only heightened my curiosity. So, fortified by a small grant from the City of Los Angeles Cultural Affairs Department, and with my trusty spiral-bound Thomas Guide to the Streets of Los Angeles at my side, I set out to see where and how the saints and streets might intersect.

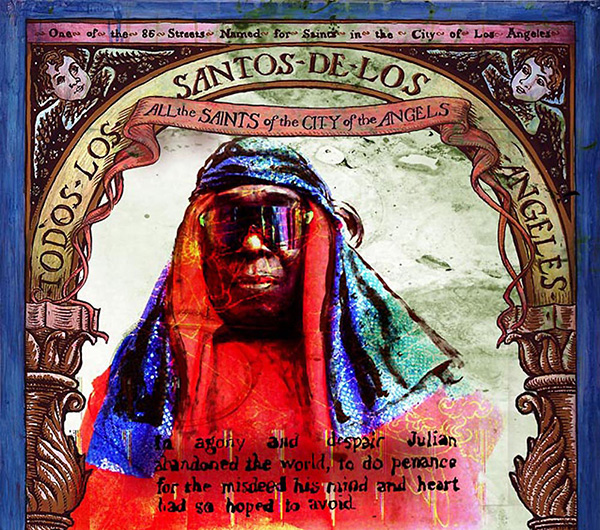

From the series All the Saints of the City of the Angels, J Michael Walker. © 2013 J Michael Walker

The connections I mapped were as rich and varied as Los Angeles’s multitude of communities themselves. But perhaps none felt more profound than that of San Julian Street, a little-traveled corridor within walking distance of the city’s historic core, and within striking distance of its heart.

San Julian Street runs north-south for a short ways—just nine blocks, from 5th to Pico—and lies one block west of San Pedro Street, at the southeastern edge of Downtown.

Formally established in 1883, it formed part of a loose-knit group of religious-themed streets in the area—Santa Clara, St. Elmo, San Leandro, and La Bondad—most of which vanished as streets were re-cut or renamed. San Julian, however, endured.

Hipsters of a certain age may recall the boisterous, contentious tenure of Gorky’s Café—a bohemian hangout and haven for coffee, conversation, and borscht—that, beginning in 1981, illuminated the southwest corner of San Julian and 8th Street for a decade until its agonizing demise in 1992.

Yet the things that drove Gorky’s to extinction—the perception of Downtown as unsafe, café patrons encountering panhandlers on their way to and from the parking lot, and homeless bundled into nearby doorways—led San Julian Street, particularly its northern half, to its rebirth as metaphor.

The name derives from one of the most popular of medieval saints, the French Saint Julien l’Hospitalier, whose life, as recounted in 13th and 14th-century manuscripts, bears resemblance to Greek legends, in a tale worthy of Shakespeare.

Julien was of noble birth and great promise, but his life was set off course by an awful curse: a foretelling that he would kill his parents. To avoid this fate, Julien wandered the earth “until Fortune wearied of him.” His parents, heartbroken, despaired of ever finding him alive.

Over time Julien made a new life for himself, even married, and settled down far from the land of his birth. But fate brought his parents to his door, as pilgrims; and in a terrible misunderstanding—confusing his father and mother with adulterous lovers— he killed them in the dark of night.

Again Julien set off, in penance this time, to wander in tatters and without shoes, eating bread where it was found, drinking “from many an unhealthful spring.” And again, eventually he settled down, by the side of a road, and built a little hovel. There he welcomed other wanderers, offering them a night’s meal and lodging, while refusing any pay.

One night it stormed—all sleet and heavy rains—and Julien answered a cry for help from an ancient beggar, weak with hunger and festering wounds. Julien brought the feeble man inside, fed him, and embraced him through the night to warm his chilled bones.

In the morning light the stranger revealed himself to be an angel and spoke: “Julien, now may you rest. All is forgiven.”

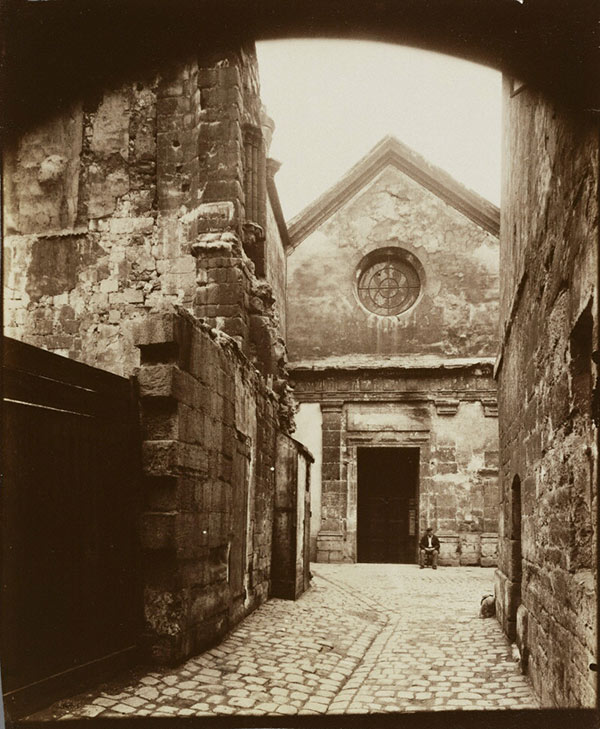

Another Saint Julien in a big-city labyrinth: the Church of Saint Julien le Pauvre in Paris, captured in 1898 by Eugène Atget. Albumen print, 8 1/2 x 7 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 90.XM.123

Over the past 35 years, San Julian Street has become the central gathering place for Los Angeles’s homeless population. When I first visited, in 2000, the sidewalks would fill each evening with hundreds of men and women, jostling for a tiny space of relative warmth and uncertain safety.

Like most saints, Julien has many patronages, some of which now seem curious (circus workers, for example). But, given the presence of SRO hotels on San Julian Street, his patronage of hotel-keepers and innkeepers makes some sense.

Something more profound, however, emerges from considering Julien’s relationship to two other groups: wanderers and providers of shelter.

His noble birth had prepared Julien for a life of relative ease, but an unexpected curse altered his life irreparably. In a similar way, most of the homeless had jobs and families before crises took their toll, and fully one-third suffer severe mental illness—a curse, in its own way.

Yet the cardinal chapter of Julien’s story—the transition that gives his life meaning—is his evolution from a wanderer to one who aids wanderers. Not only does this speak to restoration and redemption but it also provides us with a challenging template for viewing others, the homeless most especially.

Saint Julien was a homeless man who, over time, discovered empathy and put the welfare of others first, becoming a saint in the process. Homelessness, therefore, does not define him; it describes a period, a stage, in his life.

We do well to take this into consideration when next we see a homeless person, or vote on funding for housing. The condition of the people on San Julian Street represents just a moment in lives of remarkable, unimaginable potentiality.

Text of this post © Zócalo Public Square. All rights reserved.

See all posts in this series »

J Michael’s sincerity boggles my mind, as a native Angeleno filled with skepticism, grown up with sarcasm as a way of life, it is a delight to read J Michael’s writing.

This enlightening article echoes the depth to which writer and artist, J. Michael Walker has thrown his heart into the current life and fading history of our City of the Angeles.

For many years it has been a relentless pursuit which this amazing individual fights to never let any of it fade, as provided by this most honorable reflection of the Street of San Julian.

Thank you, once again, J. Michael Walker.