The history of Tunisia in the nineteenth century, prior to French colonization, is a subject of great interest—yet has been largely ignored and little understood by both scholars and the public.

Part of the Ottoman Empire since the late sixteenth century, Tunisia was governed from 1705 by the Husaynid dynasty with the Bey as the ruler of the kingdom. In 1957, when the Tunisian Republic was declared, the last of the Beys was overthrown. This was one year after the end of French colonization, which lasted from 1881 to 1956. From this moment on, the period of history known as the “Age of the Beys” was systematically disregarded by the new authorities, who were more focused on their own initiatives than on those of the ancient regime. After the new Tunisian Republic was established, the artistic heritage held by the ruling classes during the “Age of the Beys” was confiscated, and then ignored. Residences and their artistic contents were forgotten and sometimes destroyed. During the ensuing 60 years, important collections were removed from the eyes of a public that was sometimes not even aware of their existence.

The story of the palace of Qsar es-Saïd symbolizes precisely this rejection of the “Age of the Beys.” Located just a few hundred meters from the Bardo Museum in Tunis, Qsar es-Saïd, the “Palace of Joy” in Arabic, was the last royal residence of Sadok Bey, the final ruler before colonization, who reigned from 1859 until his death in 1882. In this very palace, on May 12, 1881, he signed the historic Treaty of Bardo that established the Protectorate of Tunisia. However, the edifice was abandoned at the beginning of the twentieth century and subsequently used as a hospital. Transformed into storage in the 1980s, the building became a warehouse where the Tunisian National Institute of Heritage transferred many items from the Bardo Palace that had originally been held in the royal collection. A shining example of Tunisian palatial architecture, Qsar es-Saïd displays the influence of European and Italian styles then prominent in royal circles

Qsar es-Saïd palace, view of the Salon d’honneur, or formal reception room

Qsar es-Saïd has witnessed many significant moments in history, and it was also the location of the recent exhibition The Awakening of a Nation: Art at the Dawn of Modern Tunisia (1837–1881) (L’éveil d’une nation: l’art à l’aube d’une Tunisie moderne), held from November 27, 2016, to February 27, 2017. The palace itself, which stands as a jewel of nineteenth-century architecture, and the important collections within were the impetus for the show.

To mount this ambitious exhibition, the first task was the restoration of 25 paintings, selected for their historical significance and aesthetic appeal from the many abandoned in the palace. In partnership with the Rambourg Foundation, a local workshop was set up to employ a dozen Tunisian restorers to clean and restore these 25 canvases. It was during this work that the theme of the exhibition really took shape. We decided to focus on the important period of the reforms of the Tunisian state, 1837 to 1881, when modern Tunisia became the stage in the Arab world for political, social, and intellectual innovations. Tunisia became the first Arab state to abolish the slave trade, to give equal rights to religious minorities, and to implement the first constitution of the Arab and Islamic world.

Above: Sadok Bey Bedroom in Qsar es-Saïd Palace from the album Tunisie et Tripolitaine, compiled ca. 1880. The Getty Research Institute, 2005.R.2. Below: Interior view of Qsar es-Saïd palace in 2015, prior to restoration, showing paintings stacked in the same alcove as in the image above.

Displaying works of art alongside rare objects and historic documents, the exhibition allowed Tunisians to reassess this historic period and gain a better understanding of the complex factors affecting the formation of the modern state. Choosing this theme helped us shed light on the splendor of the Tunisian court in a post-revolutionary context, as opposed to solely celebrating the Beys dynasty. Likewise, the exhibition coincided with the sixtieth anniversary of Tunisia’s independence and the fifth anniversary of the 2011 revolution, the starting point of the Arab Spring that led to the fall of president Ben Ali, who had perpetuated this ignorance of modern national history.

The Awakening of a Nation showed how the arts in Tunisia were heavily influenced by Europe in the 1800s, just as the country was drawing closer politically to Europe and the US and becoming less tied to the Ottoman Empire. This influence is illustrated by the 1846 journey of Ahmad Bey to Paris, the first trip made by a Tunisian monarch to meet the king of France. During this trip Louis-Philippe bestowed magnificent gifts on his visitor, including Parisian furniture, a tapestry, and paintings. These presents were among the nearly 200 items on display, including royal thrones, official costumes, ceramics, furniture, manuscripts, sculpture, sketches, paintings, a Gobelin tapestry, and late-19th-century glass negatives.

The Constitution of 1861 was the centerpiece of the show, along with the first-ever public display of the Declaration of the Abolition of Slave Trade, ‘Ahd al Aman (the Security Covenant), which guaranteed equal rights to all Tunisian citizens, notably the Jewish community. Because of their prominence and beauty, the 25 restored paintings formed the connecting tissue of the exhibition. Works by Charles Gleyre, Franz Xaver Winterhalter, Charles-Philippe Larivière, and John Woodhouse Audubon bore testimony to the links between Tunisia and western nations and showed how tastes were changing in circles of power. Nineteenth-century Tunisian artists were also represented: Ahmad al Judali and Ahmad Osman, whose works witness the political use of art inside Tunisian palaces.

But what really brought alive the themes of the show was the physical exhibition space and its history. Qsar es-Saïd features an Italianate design and combines European decoration with traditional local ceramics of different colors and shapes; together, these create a complex synchronicity of eastern and western influences that characterize the Tunisian identity during the period of reforms.

Installation view of The Awakening of a Nation, showing the gallery on the art of living under the reign of Sadok Bey

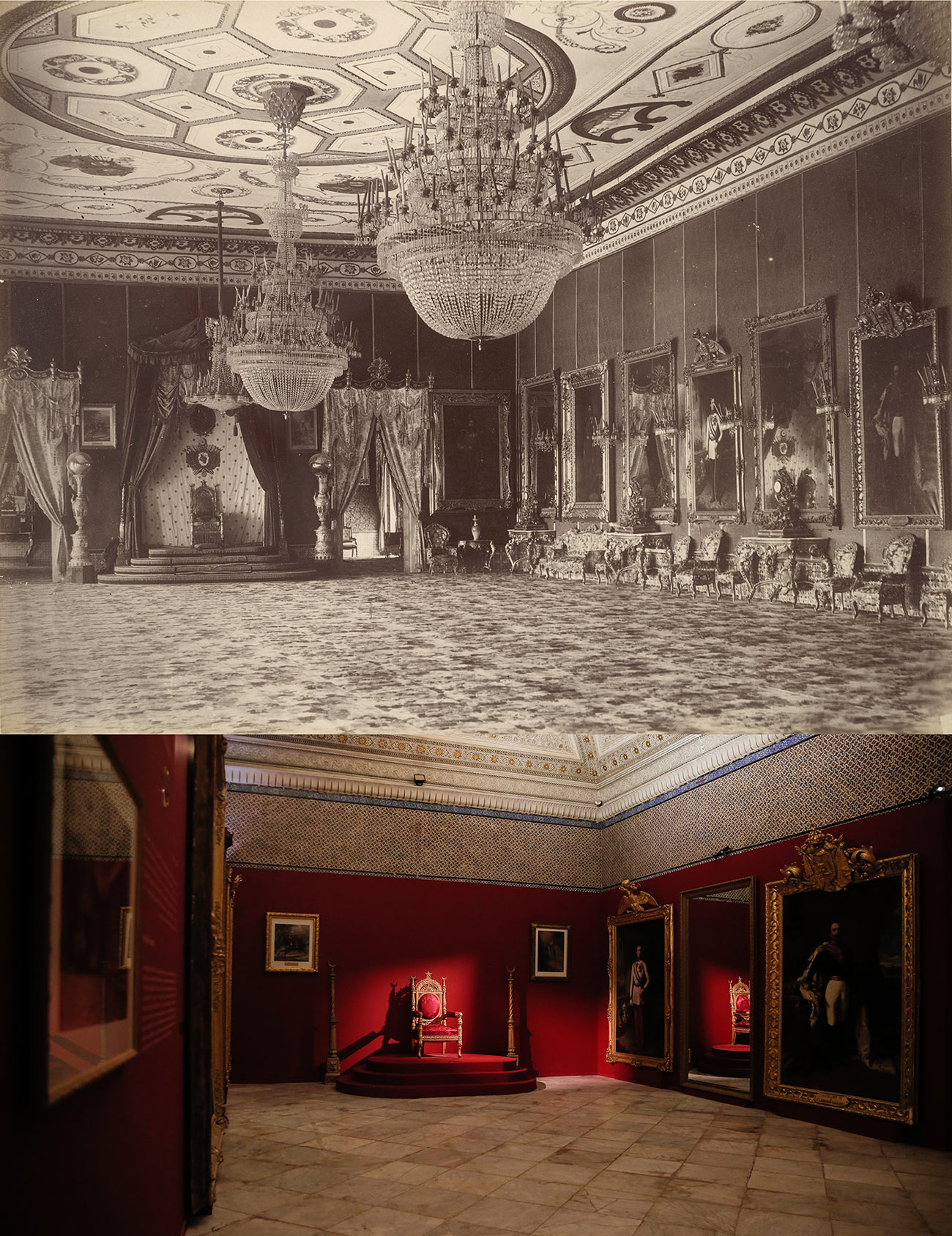

Inside the exhibition space, the throne room of the Bardo Palace was recreated as a period room. The Bardo Treaty was presented to the public for the first time, along with the pedestal table made of Carthaginian marbles on which it was signed—and both in the very room where the event took place. These recreations were facilitated by photographs from 1870 to 1880 taken in the closing days of French colonization. Photographic prints were important resources in mounting the exhibition, especially where records of paintings and works of art could not be located in the pre-colonial archives. In the absence of specific information, during our research we had to make use of various sources abroad, in particular those of the Getty Research Institute, whose photographs of the throne room made it possible to recreate it with accuracy. One historic photograph, also reproduced in the catalogue, was placed next to the installation in order to illustrate the room’s original appearance.

Above: Bardo Throne Room from the album Tunisie et Tripolitaine, compiled ca. 1880. Albumen print. The Getty Research Institute, 2005.R.2. Below: re-created throne room in Qsar es-Saïd Palace, 2016

In a room dedicated to the Jewish minority, we showed photographs from the Research Institute’s magnificent Al Djazair and Tunis album. These, and the Judaica on display, were a reminder of the importance of the Jewish community and the role they have played in the history of the country. Other photographs bore witness to the lives of dignitaries who contributed to the process of modernization. But the most fascinating photographs were those of the palace itself, especially those showing the Bey’s bedroom, which enabled us to imagine the richness and atmosphere of the palace as it had been.

A Tunisian [Jewish] Woman from the album Al Djazair and Tunis, compiled 1881. Albumen print. The Getty Research Institute, 2001.R.20

We are now working to transform the Qsar es-Saïd Palace into a permanent Museum of Modern Art and History that would inform Tunisians and foreign visitors about our national heritage and the development of the country. The revolution of 2011 had global consequences. For Tunisians, it was a wake-up call to increased awareness and respect for the history of our country and the importance of preserving our collective memory.

Exterior of Qsar es-Saïd palace showing the entrance to the exhibition L’eveil du nation (Awakening of a Nation)

La Descente des Marches (Descending the Stairs), circa 1876, Ahmed Osman. Tunis, National Institute of Heritage, Qsar es-Saïd collection

Paintings in the Treaty Room of Qsar es-Saïd Palace within the exhibition The Awakening of a Nation. At center left, the Gobelin tapestry Portrait of Louis-Philippe, King of the French, 1836–1840, Louis Hersent. Tunis, National Institute of Heritage, Qsar es-Saïd collection

Gallery about Tunisian diplomacy in the 1860s within the exhibition The Awakening of a Nation. At right, The Meeting between Sadok Bey and Napoléon III in Algiers, 1862, Alexandre Debelle. Tunis, National Institute of Heritage, Qsar es-Saïd collection

Alcove within the exhibition The Awakening of a Nation, showcasing a selection of Judaica

Nineteenth-century Tunisian ceramics on display within the exhibition The Awakening of a Nation

Mustapha Khaznadar, 1846, Charles-Philippe Larivière. Tunis, National Institute of Heritage, Qsar es-Saïd collection

Military and ceremonial uniforms, circa 1850–80, on display in the exhibition The Awakening of a Nation

Mustapha Ben Ismaïl, 1874, Rocco Larussa. Private collection

George Washington, 1838, John Woodhouse Audubon. Tunis, National Institute of Heritage, Qsar es-Saïd collection

The author pursued research for the exhibition using the Getty Research Insititute’s special collections in 2016 with the support of a Getty Library Research Grant.

All exhibition photos courtesy of Ridha Moumni

Dear Mr. Moumni, Congratulations on this exciting exhibition. I hope to visit Tunisia next year, perhaps the new museum will be open. I am an art historian working on the 16thc ruler of Tunis, Muley al-Hassan, and his relations with Italy. My book focuses on an anonymous portrait of Hassan that entered the collections at Versailles in 1835. The portrait was sent to Algiers in 1930 for the Centenaire exhibition. I have consulted the book by Mme Oulebsir and corresponded with Roger Benjamin. But neither of them has any information on the Versailles portrait. I wonder if you have come across references to it in your research. I would be very grateful for any suggestions you might have.

Best, Cristelle Baskins