A peek inside the correspondence files of the Knoedler archive, as stored in archival boxes

Founded in New York in the mid-19th century, the Knoedler Gallery played a pivotal role in building important American public and private collections. The gallery cultivated a new taste for Old Master paintings among American collectors, and successfully sold many European masterpieces to prominent collections. Knoedler’s influence is evident in his correspondence with major American collectors including Henry Clay Frick, Robert Sterling and Francine Clark, and Andrew Mellon, all of which is now available for research within the Getty Research Institute’s Knoedler archive.

In 2012 the Knoedler archive joined the special collections of the Getty Research Institute, an indispensable resource for the history of art collecting in the 19th and 20th centuries. Now a five-person team, working in partnership with the National Endowment for the Humanities, has catalogued and processed the archive’s vast correspondence series. It is open to researchers for consultation (the finding aid is available online), illuminating the gallery’s stories of success—and occasional failure.

The Brukenthal Collection in Sibiu

In addition to correspondence with collectors, the archive contains letters documenting instances when the Knoedler Gallery was uncharacteristically unsuccessful in completing purchases. The most notable of these was the gallery’s ambitious attempt to acquire a Jan van Eyck and two Hans Memling paintings from Sibiu, Romania, which was designated European Capital of Culture in 2007.

Portrait of a Man with a Blue Chaperon, around 1430, Jan van Eyck. Oil on panel. Brukenthal National Museum, Sibiu. © Muzeul Naţional Brukenthal, Sibiu, Romania

The Sibiu National Museum is one of the most important art collections in Eastern Europe. It is the legacy of Baron Samuel von Brukenthal, who in 1777 was appointed governor of the Principality of Transylvania, at that time the most eastern province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The baron had pursued a brilliant political career and was an avid collector; his guests admired his Wunderkammer (“cabinet of curiosities”), which gathered books, minerals, medals, and European masterpieces, including artworks by Antonello da Messina, Titian, Lorenzo Lotto, Pieter Brueghel the Elder, Pieter Brueghel the Younger, Jacob Jordaens, and David Teniers the Younger.

Brukenthal’s collection was housed in his palace in Sibiu. When he died in 1802, his will provided for the creation of a foundation with several stipulations: his collection was to be open to the public, with free entry on certain days, and was never to be sold or destroyed. Despite the donor’s original will, beginning in the early 20th century art dealers developed an interest in purchasing valuable pictures in the collection.

In fact, in 1926 Knoedler attempted to purchase not one, but three paintings from the Sibiu Museum: Jan van Eyck’s Man with the Blue Chaperon (1430) and Hans Memling’s Portrait of a Man Reading and Portrait of a Woman Praying (both about 1480).

Portrait of a Man Reading, about 1480, Hans Memling. Oil on panel. Brukenthal National Museum, Sibiu. © Muzeul Naţional Brukenthal, Sibiu, Romania

Portrait of a Woman Praying, about 1480, Hans Memling. Oil on panel. Brukenthal National Museum, Sibiu. © Muzeul Naţional Brukenthal, Sibiu, Romania

A Transaction Gone Awry

The Hungarian art dealer Martin Porkay was the driving force behind this attempted sale. An immigrant to New York, he cofounded the Gainsborough Art Gallery with Danish chemist, industrialist, and collector Christian Bai Lihme. Also known as a suspect Rembrandt specialist, Porkay caused an outcry in 1961, claiming in the press that a Rembrandt self-portrait just acquired by the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart was a fake.

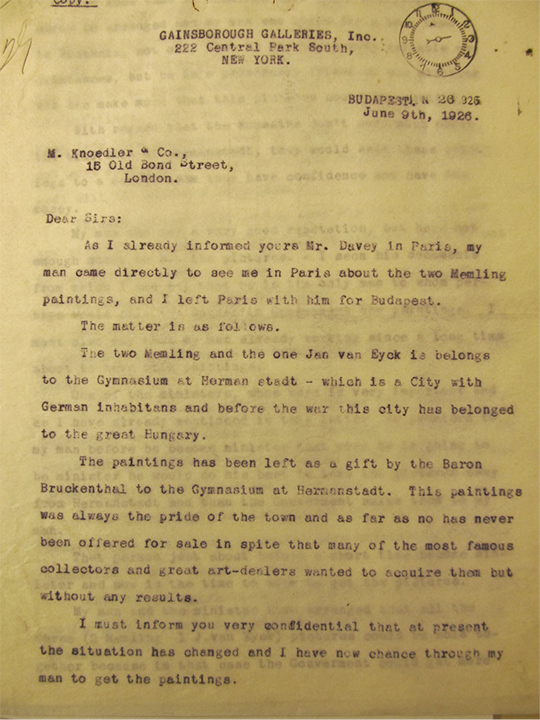

The Knoedler archive includes a letter from Porkay dated June 9, 1926, addressed to the Knoedler Gallery’s London office. Porkay offers the Van Eyck and Memling paintings from the Brukenthal Collection for purchase, a transaction to be facilitated by a member of the Romanian government. Museum staff were apparently not aware of this attempt and never wanted to sell paintings that were regarded as the pride of the city.

Letter from Martin Porkay to Knoedler offering the Van Eyck and Memling paintings from the Brukenthal Collection. The Getty Research Institute, 2012.M.54

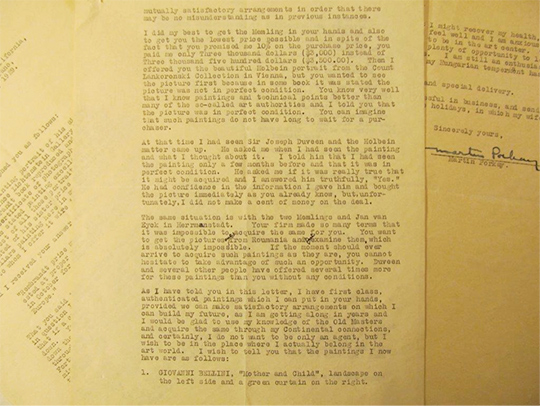

Problems with the deal arose quickly. In two letters from July 1926, Porkay and Lihme accuse the Knoedler gallery of offering the paintings for sale to a third party before concluding the deal with the Romanian government. A prior agreement had stated that the transaction must be kept confidential. This situation required Mr. Lihme’s intervention. His presence is documented in Romania in late August and September of 1926, as he tried to resolve misunderstandings and allow the transaction to proceed.

The archive is silent on what happened next—until 1929, when Porkay wrote to the gallery from his new residence in Los Angeles, where he was working as assistant to the American-Austrian film director Josef von Sternberg.

His letter summarizes the end of the story: according to Porkay, the Knoedler Gallery had imposed too many requirements, making it impossible for him to facilitate the purchase. Knoedler staff had insisted that the paintings be shipped out of Romania to be examined in person before the gallery would finish the purchase. In Porkay’s opinion, this idea had sent the deal up in smoke. As a result, the three paintings remain on display at the Sibiu Museum to this day, respecting the will of Baron Samuel von Brukenthal.

The correspondence series of the Knoedler archive contains more information about this story and many other interesting episodes in the history of the American art market. With the finding aid now accessible online, these stories now await discovery by scholars.

The Knoedler archive is available for study by qualified researchers. To consult online selected digitized stock books, sales books and commission books in the archive, visit the Getty Research Institute’s Primo’s online search page.

See all posts in this series »

I just happened upon this. I am the Tour Director of the Hegeler Carus Mansion. Olga Hegeler, the youngest daughter in this family, married Christian Bai Lihme. In the 1920’s their New York apartment was destroyed, along with a few priceless paintings. It even made Time Magazine. I am curious to learn more about Mr. Bai Lihme, if you have the time and inclination. Thank you.

Hi Tricia, Thanks for visiting the Iris and for your comment!

We were able to find a couple of pieces of information about Mr. Lihme that may be of interest. First, our archivists found the following pictures in our database that indicate they were handled by Lihme as an art dealer:

COROT, JEAN BAPTISTE CAMILLE—La Mare

DIAZ DE LA PEÑA, NARCISSE VIRGILE—Forest of Fontainebleau

DYCK, ANTHONIE VAN—La Famille Lomellini

INNESS, GEORGE—Late Sunset

ROUSSEAU, THÉODORE—Un Village dans le Berri

WYANT, ALEXANDER HELWIG—A Summer Day

Second, the author of this post found an interesting anecdote about Lihme that you may find interesting. In the book Rembrandt, andere Leute und ich (Rembrandt, the others and me), from 1959, Martin Porkay writes about his first meeting with Prince Edward J. Lobkowich in Palm Beach. Lobkowich was working at Makaroff, a famous company that imported caviar. He confessed to Porkay that he had fallen in love with the daughter of Mr. Lihme, Anita, but that he was afraid of being rejected by her family because of his job. Porkay offered to intercede for Lobkowich with Mr. Lihme, who did confess that he would like his son-in-law to be to have a better job. Lihme, however, revealed to Porkay that he had devised the idea to buy an art gallery where he could employ Lobkowich, and he asked Porkay to work with him and mentor him in his knowledge of art. They opened the gallery with an exhibition of Old Masters and soon Otto H. Kahn, one of the richest man in America and an art collector, bought a Flemish primitive from the school of Avignon. Porkay accepted, and Mr. Lihme bought the Gainsborough Gallery at Central Park West. The romance continued and Lobkowich married Anita at Lihme’s country residence “Watch Hill.”

—Annelisa / Iris editor