The Annunciation (detail), about 1434/36, Jan van Eyck. Oil on canvas transferred from panel, 35 1/2 x 13 7/16 in. The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1937.1.39. Andrew W. Mellon Collection

In late October 2012, the business records of the prominent art dealers M. Knoedler & Co. were acquired by the Getty Research Institute. This quarter-mile long archive, one of the largest archives held by the Getty Research Institute, was shipped to Los Angeles in December. A portion of it is now available for research.

Knoedler was a successor to the New York branch of Goupil & Co., an extremely dynamic print-publishing house in Paris with branches in London, Berlin, Brussels, The Hague, and New York. The firm’s office in New York was established in 1848 at 289 Broadway on the corner of Duane Street near City Hall. In 1857, Michael Knoedler, an employee and manager for Goupil, bought out the interests in the firm’s New York branch, conducted the business under his own name, and diversified its activities to include the sale of paintings. The firm became one of the most important art dealers in the United States.

The M. Knoedler & Co. archive at the Research Institute includes financial records regarding purchases and sales, correspondence with collectors, and photographs of the artworks sold by the gallery. Particularly telling in the archive is the story of one of the most extraordinary art sales of the 20th century.

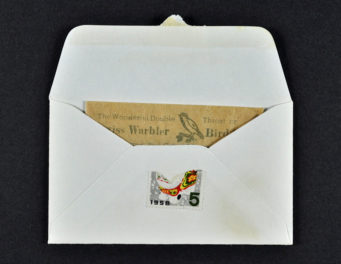

Stock books in custom-sized archival boxes in the Knoedler archive at the Getty Research Institute

One of Knoedler’s best clients was industrialist, collector and financier Andrew W. Mellon. In 1900, Roland Knoedler and Charles Carstairs of M. Knoedler & Co. were among the financier’s guests at his wedding in England. In 1921, upon his appointment as U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Mellon received a letter of congratulations from Carman Messmore of M. Knoedler & Co. The trusting and long-lasting relationship between Mellon and Knoedler proved useful for a highly unusual sale, which included Jan van Eyck’s Annunciation now at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

The Annunciation, about 1434/36, Jan van Eyck. Oil on canvas transferred from panel, 35 1/2 x 13 7/16 in. The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1937.1.39. Andrew W. Mellon Collection

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Soviet government was continuously in need of foreign currency, as it faced economic sanctions on the international market. For years, there were rumors that it might resort to selling its treasures from the Hermitage Museum, which had been founded in the 18th century by Empress Catherine the Great. European dealers monitored the situation and agents took the arduous train trip to Leningrad to investigate the possibilities of such a sale. Most came back empty-handed. A newspaper in Germany had announced that Joseph Duveen, who directed Duveen Brothers, would buy the entire Hermitage in bloc. However, Duveen did not succeed in purchasing a single painting from the Hermitage. This unusual feat would be that of Knoedler, with Mellon as client.

Because Mellon was hostile to the USSR’s communist regime and had enthusiastically supported the United States’ refusal to grant official recognition to the communist Soviet Union, he was an unlikely customer for such a sale. As U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, he opposed Stalin’s attempts to penetrate the American market with cheap goods. However, along with two other collectors who purchased artworks from the Hermitage, Armenian oil magnate Calouste Gulbenkian and Armand Hammer who conducted business in the Soviet Union in the 20s, Mellon had the power to influence the international economic context for the Soviet government.

From Leningrad to Washington, via New York (Knoedler), London (Colnaghi), Berlin (Matthiesen Gallery), and Moscow (Mansfeld), agents and dealers communicated by telegrams and negotiated the collector’s purchase. Stock books and sales books document the purchase of the 21 paintings that Mellon acquired through this chain of intermediaries. The entry in the sales book shown below lists a commission charged by Knoedler for two paintings in the sale, Botticelli’s The Adoration of the Magi and Rembrandt’s Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife.

Page from a January 1931 Knoedler sales book indicating the sale of Botticelli and Rembrandt paintings to Andrew Mellon. The Getty Research Institute, 2012.M.54

Staff at the Hermitage Museum, reluctant to facilitate the sale of Jan van Eyck’s Annunciation, claimed that no “Van Dyck Annunciation” existed in the museum’s collection, so no painting could be delivered. However, this sale would be completed, as well as transactions with other collectors until 1934, when a moratorium was put on the sale of works from the museum.

The 21 paintings that Andrew W. Mellon acquired from the Hermitage would form the nucleus of the collection of the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., which he helped to create and partially financed. In 2002, loans from the National Gallery to the Hermitage included purchases made in 1930 and 1931, including Titian’s Venus with a Mirror.

Venus with a Mirror, about 1555, Titian. Oil on canvas, 49 x 41 9/16 in. The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1937.1.34. Andrew W. Mellon Collection

In his biography on Mellon, Sir David Cannadine traced the complex negotiations undertaken by Knoedler to facilitate Mellon’s purchase, as they are revealed in the firm’s records. The firm’s commission books, as well as its stock and sales books that document purchases and sales, provenance of artworks, and financial information, such as the fee received for the Hermitage sale, are now available for research. As other types of documents become available for research, updates will be listed on the Knoedler Gallery Archive page at the Getty Research Institute. The GRI plans on digitizing a portion of the stock and sales books to increase their access for research.

Update: To consult online selected digitized stock books, sales books, commission books, and letter copying books in the archive, visit the Getty Research Institute’s Primo’s online search page.

See all posts in this series »

I am wondering if I am related to the Knoedler Art Gallery founder Michael Knoedler. My great-grandfather was Adolph Knoedler who emigrated from Gmund, Wurttemberg, Germany in the 1880’s as far as I can understand. Adolph’s father and mother were Jacob and Rosa Knoedler. They had many children. If I remember correctly, the rumor was that Michael was my great-grandfather’s uncle. I believe that my great-grandfather even cam to see Michael in New York.

If anyone there can tell me anything about this, I would be very appreciative.

Thank you for writing to us. We will have to search the documentation before we can answer your question.

Thank you for your interesting blog. I was led here by a mention of this page in the Collections portion of the National Gallery of Art’s website.

Also, I happened to notice a typographical error in your blog. What should be “received” is instead “such as the fee perceived for the Hermitage sale, are now…”

Now I’m going to look up the Mellon biography you mentioned. It’s intriguing to contemplate a man so multiply talented and accomplished as Secretary of the Treasury at a very vulnerable time in modern history.

Thank you for noting the mistake. In French, the verb “percevoir” can also mean receive, such as to receive a sum of money, but you are right that in English, the verb “to perceive” can’t be used in this context. Thank you for your acute perception!