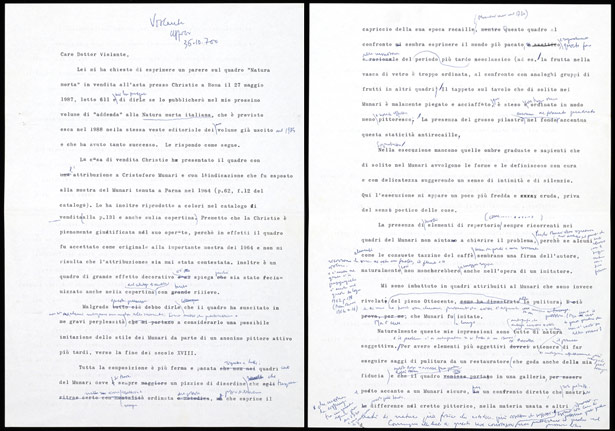

Draft letter from Luigi Salerno to Dottor Violante (recto and verso) written between 1987 and 1988 that suggests a reattribution of a still life previously thought to be by Cristoforo Munari. Luigi Salerno research papers. The Getty Research Institute, 2000.M.26

The letter pictured here exemplifies the assiduous and learned work of Italian art historian Luigi Salerno (1924–1992), whose archive is now available to researchers. The Luigi Salerno research papers are comprised of research notes, an extensive photographs archive, and correspondence that document Salerno’s career and scholarly interests. Active in Rome and prominent in the field of baroque studies, Salerno was a prolific author and an administrator involved in preserving the artistic patrimony of Rome and Lazio.

Salerno didn’t shy away from expressing his opinion on questions of attribution. In this letter addressed to “Dottor Violsnte,” possibly Marcello Violante of Chaucer Fine Arts Inc., Salerno walks the London dealer through his rationale for a change in attribution of a painting long accepted to be by artist Cristoforo Munari (1667–1720). Salerno had authored a 1984 volume on Italian still life painting that included works by Munari, a renowned still life and trompe l’oeil painter attached to the courts of the Este family in Modena and the Medici in Florence whose pieces are now in the collections of the Uffizi Gallery and the Museo Bardini, among others.

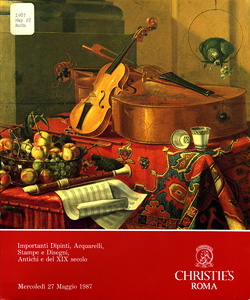

Cover of May 27, 1987, Christie’s auction catalog featuring the painting discussed in Salerno’s letter: Musical Instruments and Objects attributed to Cristoforo Munari

According to Salerno, the painting in question had been featured in a 1964 exhibition in Parma titled Christoforo Munari e la natura morta emiliana or Cristoforo Munari and Emilian still life painting, where its attribution went uncontested. It had also appeared in a May 27, 1987, Christie’s sale, where it was considered prominent enough to be displayed on the catalog’s cover.

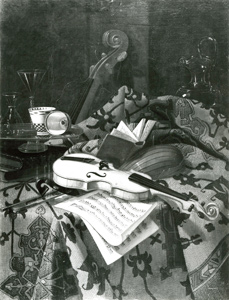

As Salerno carefully explains, the painting, Musical Instruments and Objects, had fooled experts not only because it has an appealing decorative effect, but also because it replicates elements common in Munari’s artistic repertoire. These items—including stringed instruments, a recorder, sheet music, a glass bowl of fruit, a carpet, and two ceramic coffee cups—repeatedly form part of Munari’s still life compositions. In fact, the artist duplicated these objects so often in his works that they’ve come to be accepted as a signature.

Natura morta di cucina (Kitchen Still Life), Cristoforo Munari. Private collection. Published in Luigi Salerno, La natura morta italiana, 1560-1805 (Still life painting in Italy, 1560-1805), Roma: Ugo Bozzi editore, 1984, p. 336

So why isn’t the painting a Munari? In spite of the presence of these usual clues, Salerno explains that the cold, well-ordered rigidity of the painting does not ring true. In Munari’s works, he writes, “si trova sempre un pizzico di disordine” (one always finds a pinch of disorder), and this work lacks the painterly execution, graduated shading, delicacy of form, and intimacy that Munari manages to convey in his other paintings, such as the ones shown at right and below.

Salerno concludes in his letter that if the work was to be cleaned and placed side-by-side with a genuine Munari, the differences would be clear. He unequivocally considers the painting in question to be a work by an anonymous imitator of Munari active toward the end of the 18th century, though he reminds Violante that questions of attribution are inevitably a matter of interpretation.

Still Life with Musical Instruments, Porcelain, and Citrus Fruits, Cristoforo Munari. Museo della Natura Morta, Villa medicea di Poggio a Caiano

Black and white reproductions of still-life paintings by Munari featuring his signature elements, such as musical instruments and sheet music, are included in the Luigi Salerno research papers. Still Life attributed to Cristoforo Munari. Photograph: The Getty Research Institute, 2000.M.26

Musical Instruments on a Table, Cristoforo Munari. Ministero della Pubblica Istruzione, Roma. Gabinetto fotografico, Soprintendenza beni artistici e storici di Firenze. Photograph: The Getty Research Institute, 2000.M.26

See all posts in this series »

Having studied other cases of questionable attributions, I realize that attribution is part science and part art. Salerno’s explanation that “the cold, well-ordered rigidity of the painting does not ring true,” might be impossible to prove scientifically, but makes perfect artistic sense. It is very useful to have Luigi Salerno’s archive available online – thanks.