Joseph Joel Duveen, Baron Duveen, George Charles Beresford.

Bromide print, 5 3/4 in. x 4 1/8 in. National Portrait Gallery, London. Given by Miss G. Toplis, 1939. NPG x28132. National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

With offices in London, New York, and Paris, the Duveen Brothers were one of the most influential art dealers of the early 20th century. They molded American taste in art from Barbizon paintings and English “story” pictures to Old Masters. After the firm closed, the Duveen Brothers archive was divided in two. One portion went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and was later donated to the Getty Research Institute (GRI). The other portion went to the Clark Art Institute and is currently on deposit at the Research Institute.

Both portions are now processed and cataloged, and for the first time, all of the Duveen Brothers archives are available for research in one place. Together they document the entire history of the firm, from the late-19th to the mid-20th century, with correspondence, invoices, ledgers, stock books, photographs, scrapbooks, and other business records.

The firm reached its apogee between 1909 and 1939 under the leadership of Joseph Duveen (1869–1939). His unprecedented success in art dealing was fueled by the combination of an ailing European nobility and the rise of American millionaires, such as Samuel Kress, Andrew Mellon, Jules Bache, and Henry E. Huntington. But it wasn’t just this combination that merits Duveen’s inclusion in the annals of notable dealers. With his lavish showrooms and a flamboyant style that became integral to his business tactics, Duveen was not just selling pictures; he was selling a way of life—a life of European aristocracy that did not exist in America.

Duveen’s business tactic was a mix of professional and personal: it involved meeting many of the firm’s clients’ practical needs, from organizing moves across continents to managing interior remodeling and even to storing personal cigar collections in the firm’s basement. Duveen also trained his clients to appreciate art, turning his clients into “pupils.” He attempted to persuade his clients that no great picture could be obtained except through himself. Duveen’s clients were to own “Duveen” pictures. When Huntington expressed interest in Gainsborough’s The Blue Boy, Duveen went to great trouble to acquire it, after successfully outmaneuvering other dealers. The acquisition was displayed triumphantly.

Duveen also developed a habit of criticizing artworks offered by other art dealers—questioning the artistic worth of other dealers’ pictures, or discrediting their authenticity. The latter practice landed Duveen in court, where he met his match in Andrée Lardoux Hahn.

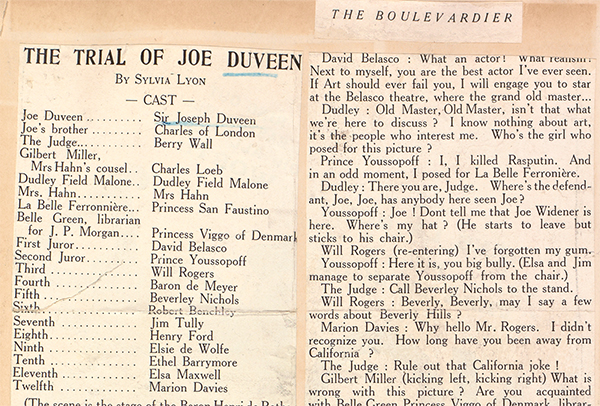

Duveen was in London when a reporter informed him that a Leonardo da Vinci painting (La Belle Ferronière) owned by Hahn was to go on sale in America. Without hesitation, Duveen refuted the authenticity of the picture, knowing the original was hanging in the Louvre. Hahn claimed that an anonymous donor to the Kansas City Art Institute had been ready to pay $225,000 for the painting, but Duveen’s exclamation voided the verbal agreement. Hahn sued Duveen for libel and sought $500,000 in damages. The trial has been described as ”the world’s most celebrated case of art litigation—a heresy case with a picture as defendant.” The Duveen Brothers archive includes a scrapbook with pages of clippings from newspapers that covered the case as it happened.

Duveen assembled a magnificent group of art historians and experts—the likes of Wilhelm von Bode, director of the State Museums in Berlin; Sir Charles Holmes, director of the National Gallery in London; Frederik Schmidt Degener, director of the Risksmuseum in Amsterdam; and art historians Bernard Berenson, Adolfo Venturi, and Robert Langton Douglas. George Sortais was the only expert called on Hahn’s behalf.

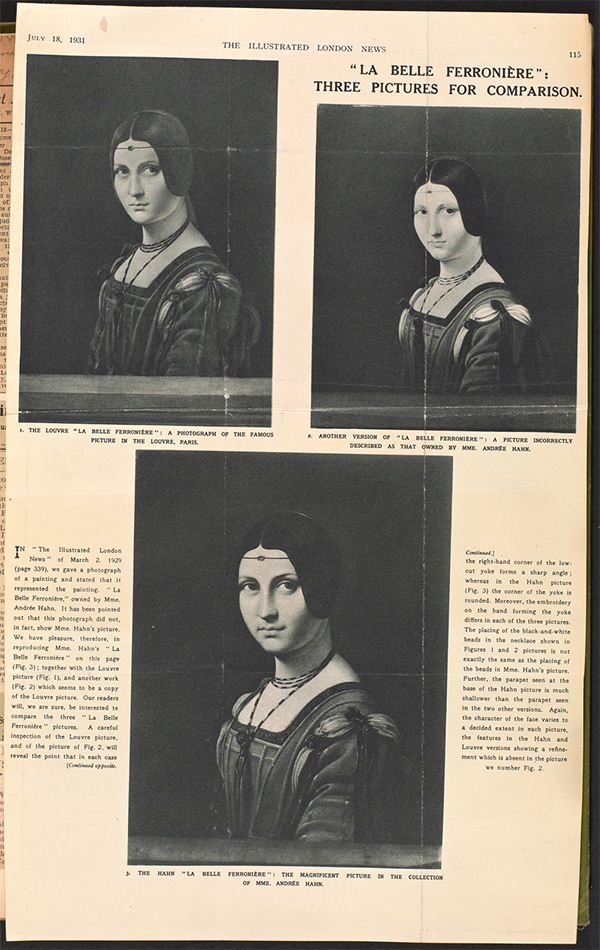

During the long trial, experts examined Hahn’s version of the painting in Paris, alongside the Louvre painting. La Belle Ferronière is a bust-length, three-quarter-view portrait of a young woman with a necklace and a jeweled headband. Close examinations of the two pictures revealed many differences. The eyes are bigger and the cheeks are fuller in the Hahn painting than in the one from the Louvre. The differences in the lips are even more striking.

Duveen and the experts, though, faced a challenging process of authentication involving X-ray photographs. The technology, used primarily for medical purposes prior to the trial, was appropriated to examine layers of paint on Hahn’s picture. The X-rays revealed corrections made to the Louvre version and other differences for which no one in the courtroom needed a connoisseur’s eye. Although the X-rays helped his defense, Duveen did not believe in technical methods for authenticating a work of art. Meanwhile, investigators had discovered that Andrée Hahn had obtained the painting from an aunt living in France who had been told by a number of Paris art dealers that the painting had no value. The alleged buyer for the Hahn painting—the Kansas City Art Institute—was an art school operating in the local YMCA.

Even with this combination of connoisseurship and scientific evidence, the jury could not reach an agreement and indicated in its pronouncement that it felt a distrust for connoisseurs. The judge ordered a retrial, but Duveen opted to settle out of court for $60,000. La Belle Ferronière is still hanging at the Louvre, while Hahn’s version, nicknamed “the American Leonardo,” was sold at Sotheby’s New York for $1,538,500 in 2010.

Duveen could be seen at times as recklessly overconfident, but in the case of La Belle Ferronière, when refuting a Leonardo da Vinci that had reappeared in Kansas, he was standing on solid ground. According to an oft-told story, Duveen once declared to his brother-in-law, René Gimpel, a French art dealer, that he would like to be remembered upon his death as the man of La Belle Ferronière. Indeed he is!

Both portions of the Duveen Brothers archives are being digitized with support from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation. Stay tuned…

See all posts in this series »

Nice Images!!!

great story!