Cesar Pelli’s iconic Pacific Design Center is one of many ’70s buildings that form the backdrop to L.A. life. Photo: Kent Kanouse on Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0

What do you get when you cross a hippie with an astronaut? You get 1970s Los Angeles architecture.

I’ll explain, but first, let’s set our parameters. Many histories have been written about L.A. architecture up to 1971, when Reyner Banham made us look at this place in new ways with his seminal book Los Angeles: Architecture of Four Ecologies. And we know that in 1978 Frank Gehry reinvigorated the scene—and the writing about it—by radically remodeling his house in Santa Monica. So what happened between 1971 and 1978, and why has L.A. architecture of that time been so egregiously neglected, or let’s just say, largely overlooked? What exactly is it about the decade that is so difficult to characterize?

One of the many benefits of Pacific Standard Time Presents: Modern Architecture in L.A. is that several of the exhibitions, books, and programs begin to unearth the 1970s—the “missing years” of Los Angeles’s modern architecture. Especially as a series, the various and diverse exhibitions and programs create a wooly mosaic of that unruly period and offer fruitful directions for the future of ‘70s scholarship.

Sylvia Lavin, curator of Everything Loose Will Land: 1970s Art and Architecture in Los Angeles at the MAK Center, speaks of this period as a “dominant lacuna”—an unknowable, difficult to see, funny in-between decade that produced work resistant to classification. In defining its boundaries, Lavin alludes to the “period in between” the city’s early ‘60s amorphousness and its transformation by the early ‘80s into an entity so well delineated that it would become “the icon of a post-apocalyptic imaginary.” The exhibition and accompanying catalogue also convey that in-between quality, featuring projects that straddle art and architecture, as artists and architects shared tools and procedures, viewers became active participants, space itself became a medium, and works engaged light in new, far-out ways.

A far-out moment at the MAK Center, site of the architecture exhibition Everything Loose Will Land

Everything Loose Will Land packs a lot into those four main spaces of the Schindler House—with an ingenious installation by local architects Johnston Marklee—and brings to the fore the shifting socio-political-economic historical moment. The exhibition evokes the aftermath of ‘60s Pop art (Archigram, Peter de Bretteville with Keith Godard), trippy futurism (Craig Hodgetts), megastructures (Gruppo 9999, Paolo Soleri), psychedelia (John Whitney), and the decade’s increasing preoccupations, such as ecological alarm (L.A. Fine Arts Squad), the women’s movement (Judy Chicago, Sheila Levrant de Brettville), conceptual art (Bas Jan Ader, Nancy Holt and Robert Smithson), and space-age technology (Peter Jon Pearce and E.A.T [Experiments in Art and Technology]). Now are you starting to see the hippie and the astronaut?

Most remarkable about Lavin’s exhibition is how it brings to light unknown projects and collaborative ventures by architects and artists you thought you knew. Lesser-known work by Frank Gehry, for example, appears in three of the four rooms, including a shelving unit fronted by glass discs, a very early fish sculpture, and a drawing for a house and studio (not built) for Ed Ruscha. Wouldn’t you have liked to watch those two hash it out? Work by Peter Alexander includes drawings of his own home in Tuna Canyon and a resin box. Connections emerge: Jef Raskin, an interface designer for Apple Computer, used cardboard to create toy-like blocks called “Bloxes.” StudioWorks (WorksWest) also used cardboard for an early flat-packed chair. The exhibition visually jolts the visitor when the ‘70s overlaps with postmodernism, including pop and word-featured projects by Venturi & Rauch with Denise Scott Brown and a mirrored model by Charles Moore, and with high modernism (Cesar Pelli, with Victor Gruen).

Inside Everything Loose Will Land, which explores the cross-pollination that took place between architects and artists in Los Angeles from the late 1960s to 1980.

Seventies buildings also appear in the Getty’s exhibition Overdrive: L.A. Constructs the Future, 1940–1990, curated by Wim de Wit, Christopher James Alexander, and Rani Singh. Among the many drawings, models, videos, and art to be savored are Craig Ellwood’s Art Center College of Design and Pelli’s Pacific Design Center, just to name two examples of the large public buildings from that era that now form the background for so much of life in today’s L.A. They are so familiar that they disappear, until a curated event such as Overdrive allows you to perceive them anew.

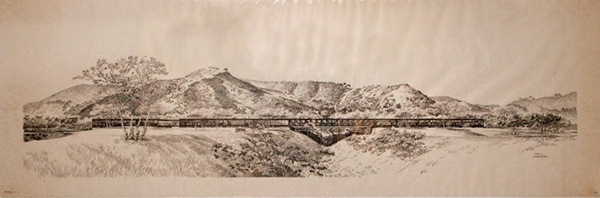

Early sketch of Art Center College of Design’s Hillside Campus, which opened in 1976. Art Center campus; perspective view, 1968, Craig Ellwood and Associates; Carlos Diniz, artist. Ink on vellum, 29 3/16 x 77 5/16 in. Courtesy of the Diniz family archive and Edward Cella Art and Architecture. Collection of L.J. Cella

The high-style modernism that was still hanging on in the ‘70s, as seen to great effect in Overdrive, helped lead to mutiny by the decade’s end. A major architectural shift occurred, one well captured in the exhibition at the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc), A Confederacy of Heretics: The Architecture Gallery, Venice, 1979, curated by Todd Gannon, Ewan Branda, and Andrew Zago. (Check out the SCI-Arc Media Archive for amazing ‘70s footage of lectures by the various “heretics”—Coy Howard, Eugene Kupper, Roland Coate, Frederick Fisher, Frank Dimster, Gehry, Peter de Bretteville, Thom Mayne and Michael Rotondi of Morphosis, Eric Owen Moss, Craig Hodgetts and Robert Mangurian of Studio Works—and more.) That story will be no doubt hotly debated in a not-to-be-missed symposium this weekend at SCI-Arc where most of the faculty are neither hippies nor astronauts, but something else again.

That phrase, by the way, comes from someone who has appeared at many Pacific Standard Time Presents events, architect Neil Denari. I asked him how he would describe what was happening here in the 1970s, and he replied it was about the “the Hippie and the Astronaut”—in other words, the hangover of the 1960s messy idealism and activism, mixed with space-age technological advances. L.A.’s architecture embodied that duality. No wonder it’s taken us until now, with these exhibitions on our local architectural history, to begin to understand that crazy, funky era.

Note: On Sunday, June 23, the MAK Architecture Tour for Everything Loose Will Land will feature works by architects mentioned above (Gehry, Alexander, and Denari)—as well as one ‘70s building: Morphosis’s 2-4-6-8 House from 1978.

Comments on this post are now closed.