Powdered saffron, simmering roots, crushed leaves…no, it’s not what’s cooking in the kitchen, but what’s been cooking at the Getty Villa this quarter for the UCLA/Getty Master’s Program in the Conservation of Archaeological and Ethnographic Materials.

As part of a course on the technology of wall paintings, mosaics, and rock art, students are investigating different pigments and techniques used throughout history for painting murals and other surfaces. Their first assignment is to research different recipes on how ancient and historic pigments were made and then try to replicate them in the lab.

Two of the students are trying to create a pigment called madder lake, made by extracting red dye from the madder root and then combining it with inorganic materials, such as alum, to make the colorant more permanent and easier to paint with. This process involves boiling the roots to extract a red dye and then adding a salt and an alkali to the dye while heating it to create the red pigment.

Below, Elizabeth Drolet filters mixtures of dye extracted from madder roots with different inorganic materials, such as alum, lye or chalk. The different inorganic materials used produce different shades of red.

Another pigment being replicated is Maya blue, made by mixing dye extracted from the leaves of the indigo plant with clay such as palygorskite. The mixture of the organic dye with the inorganic clay makes a colorant that’s very resistant to alteration and weathering.

The Mayans weren’t the only ones who painted with this pigment. The Aztecs are thought to have also used a similar pigment for blue which combined indigo and clay, and this seems to be what was used to paint the water vessel depicting Tlaloc currently on display in the exhibition The Aztec Pantheon and the Art of Empire.

One experiment to make Maya blue involved mixing powdered indigo leaves and palygorskite clay, which was then heated using copal resin as the heat source. Though this first trial didn’t produce Maya blue, the heated copal sure made the lab smell good.

Experiments with making historic pigments are also taking place. One group is trying to make copper resinate, a green pigment made by mixing copper salts with a natural resin, such as one made from pine trees called Venice turpentine. In order to make this pigment, the students are first creating verdigris, made by exposing copper sheet to vinegar vapors, and then taking the corrosion that forms from that process and mixing it with the Venice turpentine or other pine resins. In the photo shown here, Cindy Lee Scott scrapes verdigris from copper strips.

The last ingredient on the pigment list is saffron, which was used in the painting of illuminated manuscripts. By soaking saffron in an egg white binder, called glair, the yellow color extracted from the saffron threads could then be painted onto parchment. Saffron was also used to help make imitation gold by applying the yellow colorant over tin powder applied to the parchment giving the illusion it was gold.

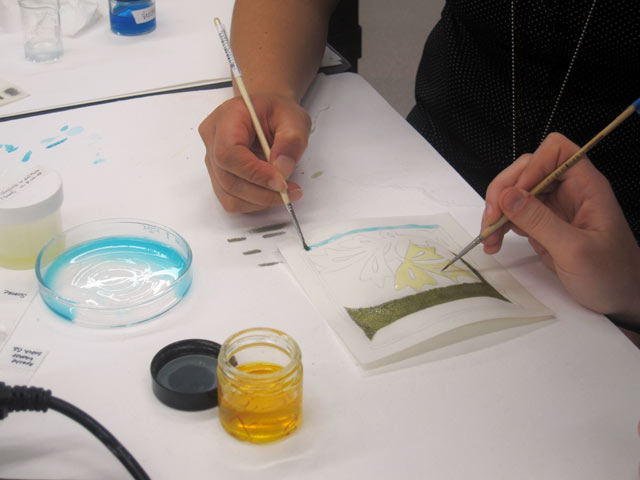

Here, students paint on parchment using saffron and other pigments mixed with glair. The letter “L” on the manuscript was painted using tin metal filings and saffron to look like gold.

With all these different pigment experiments going on in the lab, there are bound to be some interesting sights, colors, and smells. We’re all learning a lot about ancient technology by trying to actually manufacture pigments using old recipes—and we definitely have a new appreciation for the difficulty and skill involved in successfully creating these materials.

Text of this post © Vanessa Muros. All rights reserved.

It’s amazing how ancient (and not so ancient) peoples used ingredients that were on hand and developed processes to create pigments to color their world. I especially enjoyed the green pigment section. This is a fun and informative blog!

HI there

I´m so happy to see people making stuff like me and I have to say that the best way how to learn the way how the historic pigments were used is the actual preparation of pigments. I made just several pigments but actually I´m trying to create a fine ultramarine by the formula of Cennini and De Boodt so I really hope that it all go well and I´ll not spoil the material. So wish you just good luck and have fun with it .

al fondo una parte de la pared del cenote de zacalum es bastante azul como el azul maya seguramente en aquel tiempo lo usaban

I teach high school students about nanotechnology, and would like to have them make Maya Blue as a project. Thank you for doing the work of sourcing materials, developing a procedure, and discovering what works & doesn’t. Would you share those details so teachers can benefit from your work?