If you’ve ever seen travel photos of Venice or been to Venice yourself, you’re probably familiar with the Rialto Bridge. The Ponte di Rialto is one of the most popular tourist destinations in Venice and one of the most iconic landmarks of the Italian city. Even in 1594, when the bridge was only recently completed, a British traveler called it the “eighth wonder of the world.”

The version of the bridge that most people know was built between 1588 and 1591, but there’s been a bridge in this location since around 1180. The Rialto Bridge was the first bridge to cross the Grand Canal, and until the 1800s it remained the only bridge across Venice’s major waterway.

A former iteration of the Rialto Bridge, built of wood, is shown in this detail from Plan of Venice (Venetie 1500), 1500, Jacopo de’ Barbari. Woodcut. Venice, Museo Correr. Image source: École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Venice Time Machine

The Rialto district was the main commercial hub of Venice and people increasingly needed access to buy and sell goods. The first bridge built at this site was a pontoon bridge that was eventually replaced by a wooden bridge in 1264. This wooden bridge was destroyed and rebuilt several times: it burned down during an unsuccessful coup in 1310, and in 1444 collapsed under the weight of a crowd watching a boat parade during a wedding. Its last collapse came in 1524, and by then Venice decided it was time to build a more permanent and durable bridge.

Beginning in 1525, many architects submitted designs for the Rialto Bridge, but none of them was unanimously selected for the commission. The elected council overseeing the bridge’s construction deliberated and consulted several local builders to figure out how they could erect a stone bridge across the wide Grand Canal. They had a few limitations to consider: the sloped shores on either side, the need for boats to be able to pass underneath, and the practicality of having shops atop the bridge.

Andrea Palladio’s design for the Rialto Bridge, published in his architectural treatise, Quattro libri, in 1570, featured three arches that would have prevented larger boats from passing under the bridge. Although his design utilized an appealing classical aesthetic, it was rejected in favor of Antonio Da Ponte’s.

Design for the Rialto Bridge. Page from Quattro libri dell’architettura di Andrea Palladio, originally published 1570. Engraving by Giovanni Silvestrini published Siena, Appresso Alessandro Mucci, 1790–91. The Getty Research Institute, 2893-965

In 1588 Da Ponte, an elderly local builder who oversaw some of the buildings in this area of the city, claimed that he could tackle the site-specific construction challenges and took control of the project. Despite not having a fully articulated architectural design, Da Ponte invented his own system for an underwater foundation that could bear the weight of the stone. Not only did the completed bridge withstand a major earthquake in 1591, but it still stands today as one of the most extraordinary sights in Venice.

Gondolas and Regattas

Overall view (left) and detail (right) of Regatta on the Grand Canal in Honor of Frederick IV, King of Denmark, 1711, Luca Carlevarijs. Oil on canvas, 53 1/4 × 102 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 86.PA.599. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Since its construction the Rialto Bridge has been important not only as architecture and symbol, but as a venue for festivals such as the regatta. A regatta, or gondola race, was one of the most exciting events for 18th-century Venetians. Only held upon the visit of a king or the heir to the throne, regattas were a time for celebrating Venice’s wealth and grandeur. Organizers pulled out all the stops to impress and entertain the king. The painting by Luca Carlevarijs above depicts the 1711 regatta in honor of Frederick IV, King of Denmark.

The Rialto Bridge appears in the back corner, behind the lavishly decorated gondolas and festive scene in the foreground. The gondoliers, in plainer and smaller boats, are about to go under the Rialto as part of their eight-mile race along the Grand Canal.

Almost 70 years later, Francesco Guardi depicted a regatta from almost the exact same view of the bridge.

Overall view (left) and detail (right) of A Regatta on the Grand Canal, about 1778, Francesco Guardi. Pen and brown ink, brush with brown wash, over black chalk, 16 9/16 × 27 1/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2016.78. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Guardi, like Canaletto, was a view painter who captured scenes of Venice that were often sold to tourists visiting the city. Back at home, these visitors could look at their painting and fondly remember their time abroad, like we might do with a postcard today. View paintings, particularly of Venice, were very popular in the eighteenth century—so much so that critics of the time grew tired of them. They criticized view painters as lacking imagination because they so often depicted the same scenes of the Grand Canal. Compare these two paintings by Carlevarijs and Guardi: they’ve drawn almost the exact same composition, as well as depicted the same event.

However, this wasn’t out of laziness, but rather practicality. If artists wanted to depict the Grand Canal, there were very few vantage points along the canal where they could stand to capture a sketch. The canal is not lined with a walkway the whole way through; instead, houses come right up to the water. Unless you had access to one of these buildings, you were left to stand at one of the few points of public access.

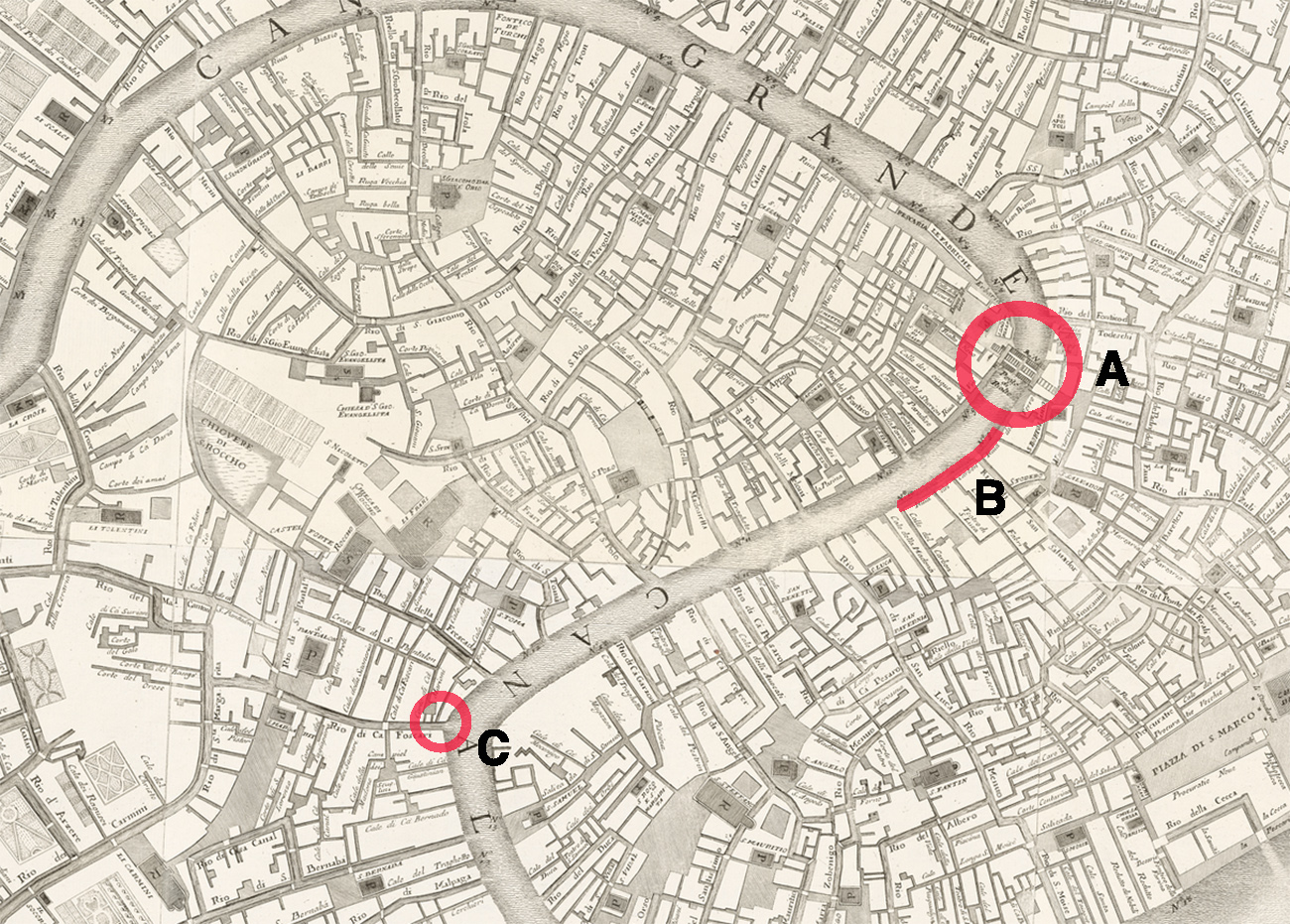

Map of Venice featuring A. Ponte de Rialto, B. Walkway along the Grand Canal where many captures of Rialto were taken, and C. Location where Luca Carlevarijs and Francesco Guardi would have stood to compose their artworks. Background image: Map of Venice, ca. 1739, Luca Carlevaris. 13 etchings, 148.3 x 204.8 cm assembled. Published as Lodovico Ughi, Iconographia rappresentatione della inclita citta di Venezia consacrata al Reggio Serenissimo Dominio Veneto…. (Venice: Appresso Lodovico Furlanetto sopra il ponte de’ Baretteri, 1739). The Getty Research Institute, 93-M1

For that reason, most painters and even photographers from the nineteenth century on have depicted the Rialto Bridge from a similar angle, either from this point where the Grand Canal straightens out or from the right bank looking north. These photographs taken between 1857 and 1865 by at least two different photographers all have very similar views of the Rialto Bridge, with only slight variations in the framing.

Clockwise from top left, details of: Rialto Bridge, Venice, about 1865, Italian. Hand-colored albumen silver print. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XC.873.5379. Ponte di Rialto, about 1865, Italian. Albumen silver print. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XC.873.5200. Bridge of the Rialto, Venice, 1857–60, Claudius E. Goodman. Albumen silver print. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XC.979.448. Rialto Bridge, 1870s, Carlo Ponti. Albumen silver print. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 84.XC.873.8350. Digital images courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Artists and photographers hoping to make souvenir images of Venice found themselves—and still today find themselves—limited by the water. Venice’s unique geography and architecture restricts access points on land and makes it difficult to find a vantage point that captures the Grand Canal and the city’s beauty. For these reasons—not for lack of creativity or inspiration— images of Venice and the Rialto Bridge are often taken from very similar angles simply because of what is actually possible. Next time you see an image of Venice that looks familiar, that’s probably why!

Comments on this post are now closed.