Grave Relief of Publius Curtilius Agatus, Silversmith, A.D. 1–25, Roman. Marble, 31 7/16 x 23 1/16 x 12 1/2 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 96.AA.40. Bruce White Photography

Creativity looks easy, but that’s a carefully staged illusion—artists invest more effort than we often give them credit for. Forget absinthe-drinking and angsting on a velvet chaise; artists have always faced hard labor, mental strain, and more than a few occupational hazards.

Hard Labor

Making art can require Olympian strength and endurance. Before the advent of power tools, weeks and even months of hard labor were required for sculptors to hammer, chisel, rasp, and hand-drill their way into stone. Potters, metalworkers, and glassblowers not only wield clay, ore, and silica, but wrestle flames. This Greek vase offers a particularly vivid depiction of the brute strength required for the blacksmith’s art (zoom image here).

In ancient Greece and Rome artists didn’t merely toil like slaves; sometimes, they actually were. We know of at least one Greek vase-painter who signed his wares “the slave,” and the Roman silversmith carved above is identified by inscription as a freed slave—once of ancient Rome’s sizeable enslaved artisanal class. Though on a hopeful note, his tony finger ring and attire (a toga, the Roman equivalent of a tuxedo), suggest that, in his case at least, artistic skills could sometimes be a ticket to prosperity.

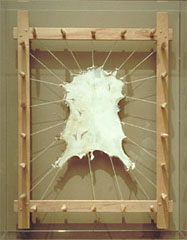

Post-dehairing, the stretching can commence

Simply preparing the raw materials for art can be hard labor in itself. To make parchment for an illuminated manuscript, for example, involved gore, toxic brews, and lots of strenuous stirring:

“After being flayed, the skin is soaked in water for about 1 day. This removes blood and grime from the skin and prepares it for a dehairing liquor. The dehairing liquor was originally made of rotted, or fermented, vegetable matter, like beer or other liquors, but by the Middle Ages an unhairing bath included lime…The liquor bath would have been in wooden or stone vats and the hides stirred with a long wooden pole to avoid human contact with the alkaline solution. Sometimes the skins would stay in the unhairing bath for 8 or more days depending how concentrated and how warm the solution was kept-unhairing could take up to twice as long in winter.”

Dehairing liquor? I rest my case.

Sisyphean Tasks

Sancho’s Feast on the Isle of Barataria from The Story of Don Quixote series, 1770–72, woven at the Gobelins Tapestry Manufactory after a painting by Charles-Antoine Coypel. Wool and silk; modern cotton lining, 12 ft. 2 in. x 16 ft. 7 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 82.DD.67

Artists don’t merely work hard; they also work long—in some cases years or even decades—to perfect their craft and see their work to completion. Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise took 27 years; the Watts Towers, 33. Each hard-toiling weaver at the Gobelins factory in France, which produced luxurious tapestries to warm and adorn the homes of European nobility, was only able to weave two square inches per day. The panel above? It’s 29,054 square inches.

Art history is filled with spectacular stories of years-long projects never completed. One such belongs to 18th-century curator Lambert Krahe, who set out to create an art catalogue larger than anything ever seen. He hired draftsmen to painstakingly render hundreds of paintings, which would then be transferred to copperplate to use for mass printings. Unfortunately, the process was so involved that he nearly bankrupted himself after making a grand total of…four. Two decades after Krahe’s death, an optimistic printmaker revived the project; he made it to 21 prints before he, too, sunk into bankruptcy.

On the plus side, artists can resort to the relief we all share during times of trouble: bitter complaining. The struggles of manuscript-writing monks, for example, are well documented. Favorites include, “Oh, my hand,” and “Now I’ve written the whole thing: for Christ’s sake give me a drink.”

But we’re not in the Middle Ages any more, and surely contemporary artists have things a bunch easier. Right? Hardly. Just last year LACMA and Michael Heizer’s Levitated Mass proved it takes a village to move a…giant rock. A feat of engineering and a never-before-done-purposing of Los Angeles surface streets, this installation was conceived in 1969 and not completed until 40 years later. Artist Sandy Rodriguez, an education specialist at the Getty Museum, described to me the lengthy work involved in her performance piece “Ofrenda a Los Santos Inocentes,” which she is in the process of restating. It includes concepting, choreography, runway rental, elaborately hand-crafted costumes, and painstakingly created robot skeleton babies. Yes, I did just say “robot skeleton babies.” Do those look easy to make?

“Ofrenda a Los Santos Inocentes,” Sandy Rodriguez and Guadalupe Rodriguez. Left to right: Rainbow Underhill as Frida, Sandy Rodriguez as La Llorona, and Ben Garcia as Diego. Photo by Gil Ortiz, courtesy of Tropico de Nopal Art Space

Toxic Beauty

Pomegranate & Bird, pattern #509 from Wallpaper Sample Book 1, between 1915 and 1917, William Morris. Printed paper, 21.5 × 14.5 in. Brooklyn Museum, 71.151.1. Purchased with funds given by Mr. and Mrs. Carl L. Selden and Designated Purchase Fund

For plenty of creative folks, “suffering for art” isn’t just a metaphor. William Morris, famed for his beautiful textile designs, is believed to have used arsenic in his green pigments. Morris turned a blind eye to the negative effects: he was on the board of a lucrative arsenic-mining company, after all. Unfortunately, it was those who bought his tapestries and wallpapers who really suffered—when left in damp areas of the house, fungi caused changed the arsenic into a highly toxic substance called trimethylarsine.

While Morris went on to live a long life, some artists fared less well. Caravaggio, who was famously very messy with his (lead-based) paints, is thought to have died of lead poisoning. Other famous artists thought to have fallen victim to their materials include Goya and Van Gogh.

Undaunted, today’s artists aren’t afraid to take on dangerous materials. MOCA at the Geffen Contemporary recently featured the work of Cai Guo-Qiang, whose work literally blew up outside of the museum. (On purpose, don’t worry!) Using gunpowder to make drawings, Cai works with sky-high temperatures and supernatural subjects.

So artists really do work hard: whether chipping away at marble, getting physical with paint, or simply or doing the mental labor of imagining the new, art is a tough job…even if, when done skillfully, it often looks like the easiest thing in the world.

See “Ofrenda a Los Santos Inocentes,”and a dozen other Walking Altars at the the Catrina Ball!

Saturday, October 12, 2013 at 8:00 PM – Sunday, October 13, 2013 at 12:30 AM (PDT)

Santa Ana, CA

Orange County Contemporary Center for the Arts

117 North Sycamore Street

Santa Ana, CA 92701

https://www.eventbrite.com/event/7778185763

Dust off your dancing tacones, wear your finest Catrina and Catrin attire, and celebrate with us as we fundraise for Santa Ana’s Noche de Altares, the largest Dia de los Muertos event in Orange County.

This year, LA and OC artists are designing “Walking Altars” that capture the essence of a Day of the Dead altar and will be on display on the runway.

All proceeds go to Noche de Altares.

https://www.eventbrite.com/event/7778185763