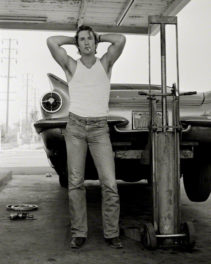

Harry Smith at Allen Ginsberg’s Kitchen Table, New York City, 16 June 1988, 1988, Allen Ginsberg. © Allen Ginsberg LLC

The Getty Research Institute has acquired the archive of Harry Smith (1923–1991), an American artist best known for his experimental films and his Grammy-award winning Anthology of American Folk Music. A multidisciplinary artist, he worked in painting as well as film. He also amassed a body of original artworks that includes string figures, typewriter drawings, and color drawings of his “border art” designs for books.

Such an output is by no means typical of midcentury artists, but Smith was not a conventional artist. Moreover, he was both an artist and an avid collector and considered his personal collections to be an integral part of his art making. His collections have arrived at the Getty as part of Smith’s archive. For the first time, researchers will be able to study them and to draw connections between Smith’s methods of classification and documentation in collecting, and his artistic practice.

What do we find in Smith’s collections? A great range of objects, such as tarot cards, gourds, pop-up books, folk crafts, toys, and eggshells mounted on stands made of lacquered paper-towel or toilet-paper rolls. Each type of material has its own box consisting of many variants on the theme. There is an entire box of paper airplanes, which Smith found on the streets of New York City. Whenever he picked one up, he noted the date, time, and location, much as an anthropologist would.

A first peek at Harry Smith’s collections, which were meticulously organized and ordered, upon their arrival at the Getty Research Institute. Here, a box of tarot cards.

Gourds in Harry Smith’s collections

Eggshells mounted on toilet-paper rolls in Harry Smith’s collections

Paper airplanes, annotated with date and findspot, in Harry Smith’s collections

Another big collecting project was string figures. Smith considered himself the world’s leading authority and compiled drawings and notes for a book manuscript which he never completed. These notes are now in the archive, as well as examples of string figures Smith created and collected. Beginning in the late 1980s, Smith pursued an audio recording project entitled “Materials for the Study of Religion and Culture in the Lower East Side,” in which he recorded ambient sounds (raindrops, children’s jump rope rhythms, public street sounds).

Smith’s interest in collecting diverse materials was to uncover universal patterns that applied across world cultures. He incorporated his collections into his films as well. For example, string-figure actions and eggshells appear in his monumental film, Mahagonny (set to the Brecht/Weill operatic score). He also used alchemical imagery in his films and synchronized film and painted image to blur the boundaries of individual media.

When we start exploring Smith’s collections, we are amazed that they have survived. He led an itinerant lifestyle, never had enough money, and frequently lost, sold, destroyed, and traded his own work. Scholars have not yet considered what it means to say that Smith was a painter and a filmmaker with a deep interest in collecting and categorizing materials. I believe that access to his archive will help begin to address this and other fascinating questions posed by his work.

Are the paintings there?

Congratulations. This is a most exciting acquisition.

Harry let me look through his amazing Tarot collection. I sat on the floor of his bedroom, in front of an open trunk of hundreds of decks, handling them and examining them. It was a lovely experience, and he was a lovely man.