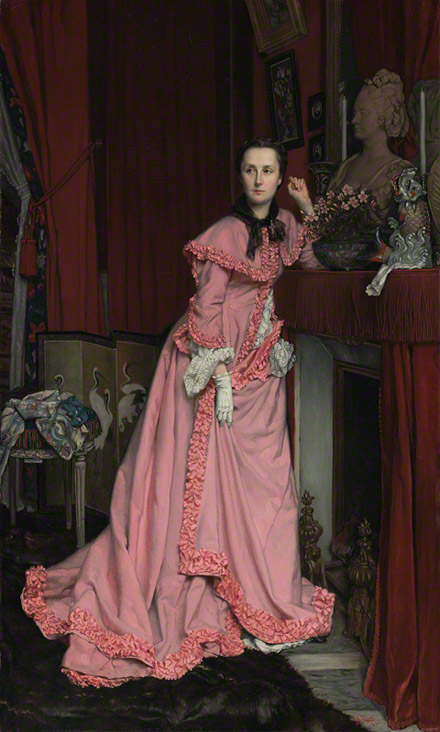

Portrait of Madame Brunet, Édouard Manet, 1860–63, reworked by 1867. Oil on canvas, 52 1/8 x 39 3/8 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011.53

Museum-quality paintings by Édouard Manet still remaining in private hands are exceptionally rare, and the Getty Museum is extremely fortunate in its most recent addition to the paintings collection: Manet’s Portrait of Madame Brunet, which goes on view at the Getty Center on Tuesday, December 13.

A compelling work with a fascinating genesis, exhibition history, and reception, the portrait hails from the decisive years of Manet’s early maturity. In the first few years of the 1860s, he devised some of his most notorious Salon paintings, including the Luncheon on the Grass and Olympia, created some of his most striking costume pieces featuring women, and made his first forays into modern urban genre with scenes like the Music in the Tuileries Garden.

The early 1860s were also the moment of Manet’s most intensive engagement with the old masters, particularly the Spanish painters Velazquez and Goya, whose strong palettes and bold, frank manners offered a model of painterly realism to the independent artist, who was intent on breaking from the restrictive conventions of the French academic establishment. Manet enlisted the art of the museum not as a conservative affirmation of tradition, but as a provocative way to confront modern French life, and he did so with an unapologetic directness and immediacy that baffled, stunned, and outraged many viewers and critics.

This dynamic between tradition and modernity is evident in the Portrait of Madame Brunet as in Manet’s other great works from the period. The sitter’s dress identifies her unquestionably as a bourgeois woman of her time. Standing before a landscape backdrop and facing the viewer directly with a placid, affectless gaze, she wears an outdoor costume consisting of fawn leather gloves, a black velvet hat, and a black paletot (a kind of short coat) over a white crinoline dress trimmed with bands of black lace—this last detail reflecting the hispanicizing influence exercised on women’s fashions by the Spanish-born Empress Eugénie during the Second Empire (1851–1870).

Philip IV as a Hunter, Workshop of Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez, about 1632. Oil on canvas. Musée Goya, Castres, on deposit from the Musée du Louvre, Paris

Madame Brunet’s pose, on the other hand, looks to the distant past. Art historians have compared her attitude to that of the Cardinal Infante Don Fernando of Austria in his 1632 portrait by Velazquez, which Manet knew through an etched copy done by Goya in 1778.

Furthermore, the broadly painted, decidedly generic landscape background situates her in a venerable tradition of royal and aristocratic portraiture, calling to mind 17th- and 18th-century examples of the Spanish, Flemish, and English schools. Indeed, the landscape seems to quote from a portrait of Philip IV of Spain in hunting dress acquired by the Louvre in 1862 and attributed at the time to Velazquez. Manet, who revered the Spanish master, promptly copied this painting in an etching, an act of copying that was also a nod to Goya.

For all the veiled quotation in Manet’s portrait, however, the signature elements of his original style are blazingly evident: in the brilliant summary execution of the mesmerizing gloves, the subtle wielding of a nuanced range of blacks in the dress, the sharp silhouetting of contours, and in the radical suppression of half-tones and shadows on the pale oval expanse of Mme. Brunet’s strongly lit face.

And just who was Madame Brunet? Her identity remains somewhat uncertain. As much as she appears a unique individual, she is also a distinctly “Manet type,” whose depicted features show a vague family resemblance to those of Suzanne Leenhoff, whom he married in 1863, or to those of his most famous model, Victorine Meurent, whom Manet began to paint around the same time.

In his 1863 exhibition at Martinet’s gallery and his landmark one-man show in 1867, the painting was displayed simply as “Portrait de Mme. B…,” in accordance with the prevailing decorum that protected sitters’ identities in public. The identification of “B…” with “Brunet” can be made on the basis of Léon Leenhoff’s manuscript inventory of the contents of Manet’s studio at his death and Leenhoff’s annotations on a card-mounted photograph by Fernand Lochard of the painting.

This Mme. Brunet, née de Penne, was married to Eugène Brunet, a sculptor whom the painter had known at least since 1857, when the two spent time studying the Renaissance masters in Florence together. A carte-de-visite photograph of M. and Mme. Brunet from one of Manet’s personal albums seems to corroborate the identification of the sitter in the portrait; one sees in both a similarly round face, large eyes, and diminutive chin (the photograph, incidentally, also provided two of the figures that Manet incorporated into his famous Music in the Tuileries Gardens of 1862).

On thinner, more circumstantial grounds, it has also been suggested that the portrait might depict either the wife of author and translator Pierre-Gustave Brunet, who shared with Manet a strong interest in Spanish painting, or a female relation of one Lieutenant Jules Brunet, who, while serving in 1863 with the French expeditionary forces in Mexico, made a drawing that served as the basis for a journalistic print that was a major visual source for Manet’s scandalous Execution of Maximilian (1867).

Whichever Mme. Brunet is depicted in the portrait, she was apparently quite upset by it when she saw it in the painter’s studio. As the critic Théodore Duret recounted years later:

One of his first portraits…was that of a young woman, a friend of his family…She was not pretty it seems. He must have, following his inclination, accentuated the peculiarities of her face. In any case, when she saw how she had been depicted on the canvas, she began crying—Manet himself told me this—and she left the studio with her husband, never wanting to see the portrait again.

Though perhaps hard for viewers today to understand, this repudiation makes sense when one compares Manet’s bold, forthright manner to the highly polished mode of society portraiture that dominated in the 1860s, and which is exemplified by the Getty Museum’s Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon by James Tissot.

Portrait of the Marquise de Miramon, née Thérèse Feuillant, Jacques Joseph Tissot, 1866. Oil on canvas, 50 9/16 x 29 15/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007.7

Next to the cultivated refinement and precise detail of such paintings, Manet’s efforts came off as incredibly awkward, ugly, and crude. Tissot’s painting, incidentally, was exhibited at the 1867 World’s Fair in Paris, and it was in direct opposition to that fair’s showcase of French art that Manet, in a gesture of independence, staged his one-man show, which featured his Portrait of Madame Brunet.

The sitter having refused the portrait, Manet retained it in his studio until his death in 1883. In the official estate inventory, the painting was listed no longer as a portrait but more generically as “Femme au gant, mode de mil huit cent cinquante” (“Woman with gloves, in 1850s dress”). It was then rechristened “Jeune dame en 1860” (“Young lady in 1860”) in the 1884 estate sale catalogue. This title was likely intended as an echo of Manet’s “Jeune dame en 1866,” exhibited to much critical ballyhoo in the 1868 Salon. As it entered the market upon Manet’s death, the Portrait of Madame Brunet was thus repurposed as a depiction of a female type and as a period fashion study, one that would have appeared charmingly out-of-date to a viewer of the mid-1880s. Additionally, and lending further luster to the painting, the provisional title “Femme au gant,” which was repeated in much of the early Manet literature, would have conjured for connoisseurs Titian’s great “Homme au gant” in the Louvre—a comparison Manet surely would have relished given his admiration for the Venetian master.

If the painting slipped conceptually between genres over the course of its early history, its actual visual appearance was also significantly altered. The picture was originally a full-length portrait, just like the Velazquez portraits to which it was indebted. An anonymous hand-drawn caricature made at time of the painting’s 1863 exhibition at Martinet’s shows Madame Brunet’s entire dress. The picture was caricatured again on the occasion of Manet’s 1867 retrospective. That illustration shows the work in its current, 3/4-length state, so we can assume that Manet cut the bottom portion off the canvas sometime between 1863 and 1867.

Cutting up a canvas was not at all an unusual thing for the artist to do in the 1860s, especially in the case of some of his larger, multi-figure compositions, but his motivations with this particular portrait are unclear. He may have been dissatisfied with the portrait for purely pictorial reasons; by reducing the conical expanse of white crinoline, he was able to simplify his composition and draw the viewer’s attention more undividedly to the sitter’s pale face, now more dramatically set off by the rich blacks of her paletot. Whatever Manet’s motives, the painting functions extremely well as a 3/4-length portrait, for which format there are also many historical precedents.

As an intriguing footnote, the painter Jacques-Emile Blanche (1861–1942), who kept the Portrait of Madame Brunet in his collection for almost 50 years, claimed that Hugo von Tschudi (1851–1911), the forward-thinking curator and museum director responsible for bringing so many great Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works to Germany, had been seriously interested in the picture for Berlin. For Tschudi, perhaps taken by Madame Brunet’s vaguely smiling, slightly detached air, the portrait was nothing less than “the French Mona Lisa”! The painting was equally prized by the great American collector Joan Whitney Payson, who like Blanche retained it for many decades, along with Vincent van Gogh’s Irises, which joined the collection of the Getty Museum in 1990.

The Portrait of Madame Brunet joins one other painting by Manet at the Getty Museum, The Rue Mosnier with Flags (1878).

The Rue Mosnier with Flags, Édouard Manet, 1878. Oil on canvas, 25 3/4 x 31 3/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 89.PA.71

Whereas this scene, painted towards the end of the artist’s life, represents his politically charged engagement with the modern city and reflects the impact of Impressionism in its broken brushwork and high-keyed palette, the Portrait of Madame Brunet, painted in the darker, more solid manner of his early work, highlights the artist’s engagement with the old masters and his ambitions in the more traditional genre of portraiture. So different in aspect and handling, the two paintings together dramatically illustrate the poles of Manet’s practice.

The addition of the Portrait of Madame Brunet to the Getty’s collection also substantially enriches the holdings of Manet’s painting in the greater Los Angeles area. Visitors to the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena can see three magnificent works: the Still Life with Fish and Shrimp (1864), the monumental Ragpicker (c. 1865–70), in which Manet adapts Velazquez’s full-length philosopher “portraits” to one of the marginal types of modern-day Paris, and the Portrait of Madame Manet (1874–76), a relatively unfinished bust-length portrait of the artist’s wife that is more informal and impressionistic than the Portrait of Madame Brunet. Striking a more charmingly intimate note is the tiny Portrait of Alice Legouvé (1875) at the Hammer Museum.

What an incredible acquisition! Congrats!