Detail of a page in the Rothschild Pentateuch decorated with Hebrew letters and marginal figures. Rothshild Pentateuch, 1296, made in France or Germany. Ink, gold, and tempera colors on parchment, 10 13/16 × 8 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 116, fol. 119v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

The recent acquisition of the Rothschild Pentateuch is a milestone in the history of the Getty Museum. It is the first Hebrew manuscript to enter to the collection and represents one of the great masterpieces of its kind. Created by an unknown artist in the thirteenth century, the manuscript contains the text of the Torah in Hebrew and a translation into Aramaic as well as commentaries, including one by the famed medieval scholar Rashi. The texts are accompanied by lively decorative motifs, hybrid animals and humanoid figures, and astonishing examples of micrography—virtuosic displays of tiny calligraphy in elaborate patterns and designs.

With a seemingly endless variety of marginalia over more than 1,000 pages, ranging from the imposing to the whimsical, the Pentateuch is one of the most extensive illuminated programs of any Ashkenazi Hebrew Bible to survive from the High Middle Ages. It was first displayed at the Getty in the exhibition Art of Three Faiths: A Torah, a Bible, and a Qur’an, along with a fifteenth-century Christian Bible and a ninth-century Qur’an.

Page from a fifteenth-century Bible on view alongside the Rothschild Pentateuch. Initial P: Saint Paul with a Sword from a Bible, about 1450, made in Cologne, Germany. Ink, gold, and tempera colors on parchment, 14 7/16 × 10 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig I 13, fol. 376. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

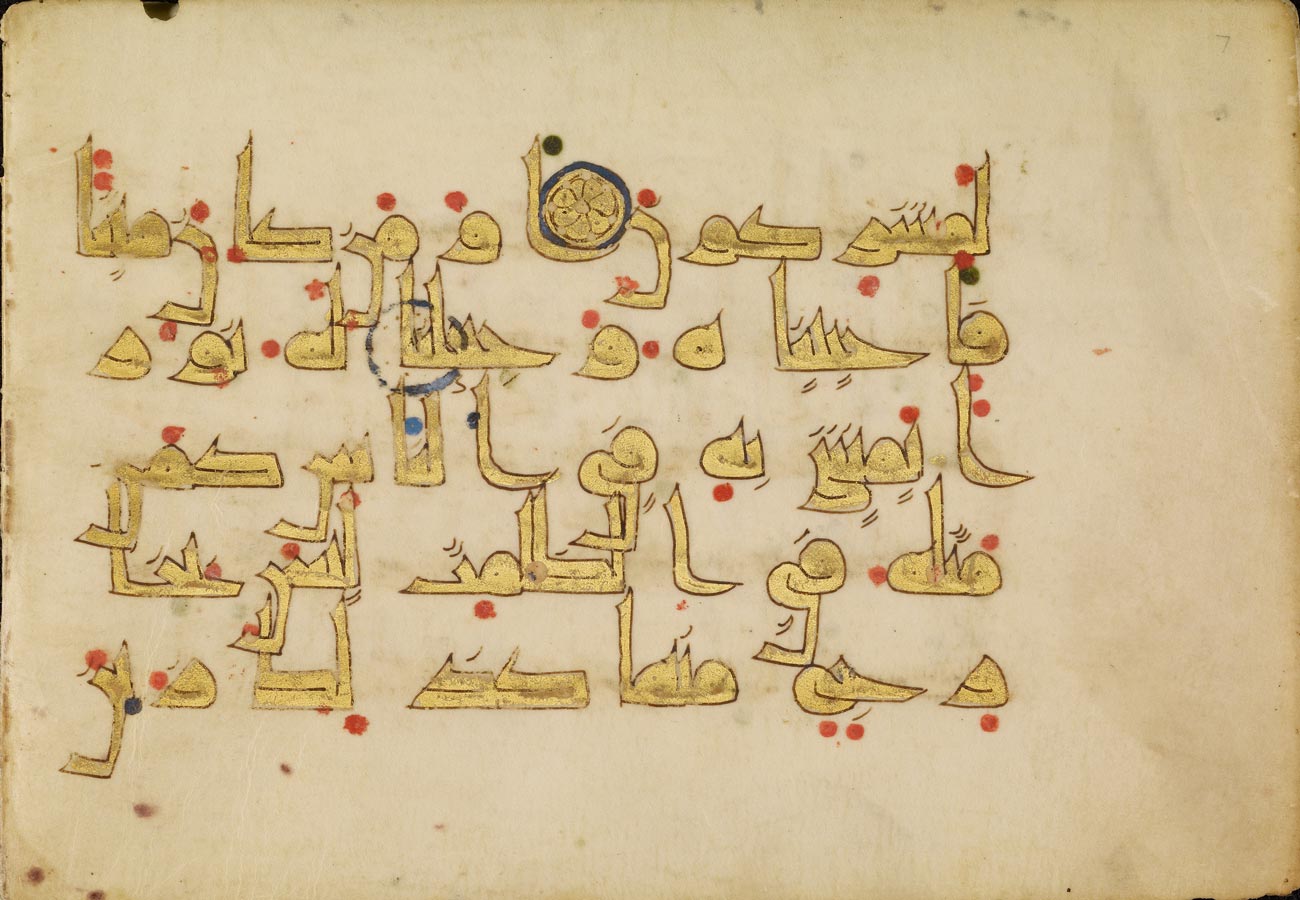

Page from a ninth-century Qur’an on view alongside the Rothschild Pentateuch. Decorated Text Page (Sūrat al-An‘ām 6: 121–122) from a Qur’an, ninth century (third century AH), made in North Africa. Ink, gold, and tempera colors on parchment, 5 11/16 × 8 3/16 in. (each leaf). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig X 1, fol. 9v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Lavish Illuminations

The text of the Rothschild Pentateuch is divided into sections to be read weekly, so the entire Torah could be recited over the course of a year. The opening of each of the five books—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy—is celebrated with monumental Hebrew initials intertwined with lively marginal figures or, in one instance, a full-page illumination.

Decorated Text Page from the Rothschild Pentateuch, 1296, made in France or Germany. Ink, gold, and tempera colors on parchment, 10 13/16 × 8 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 116, fol. 119v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

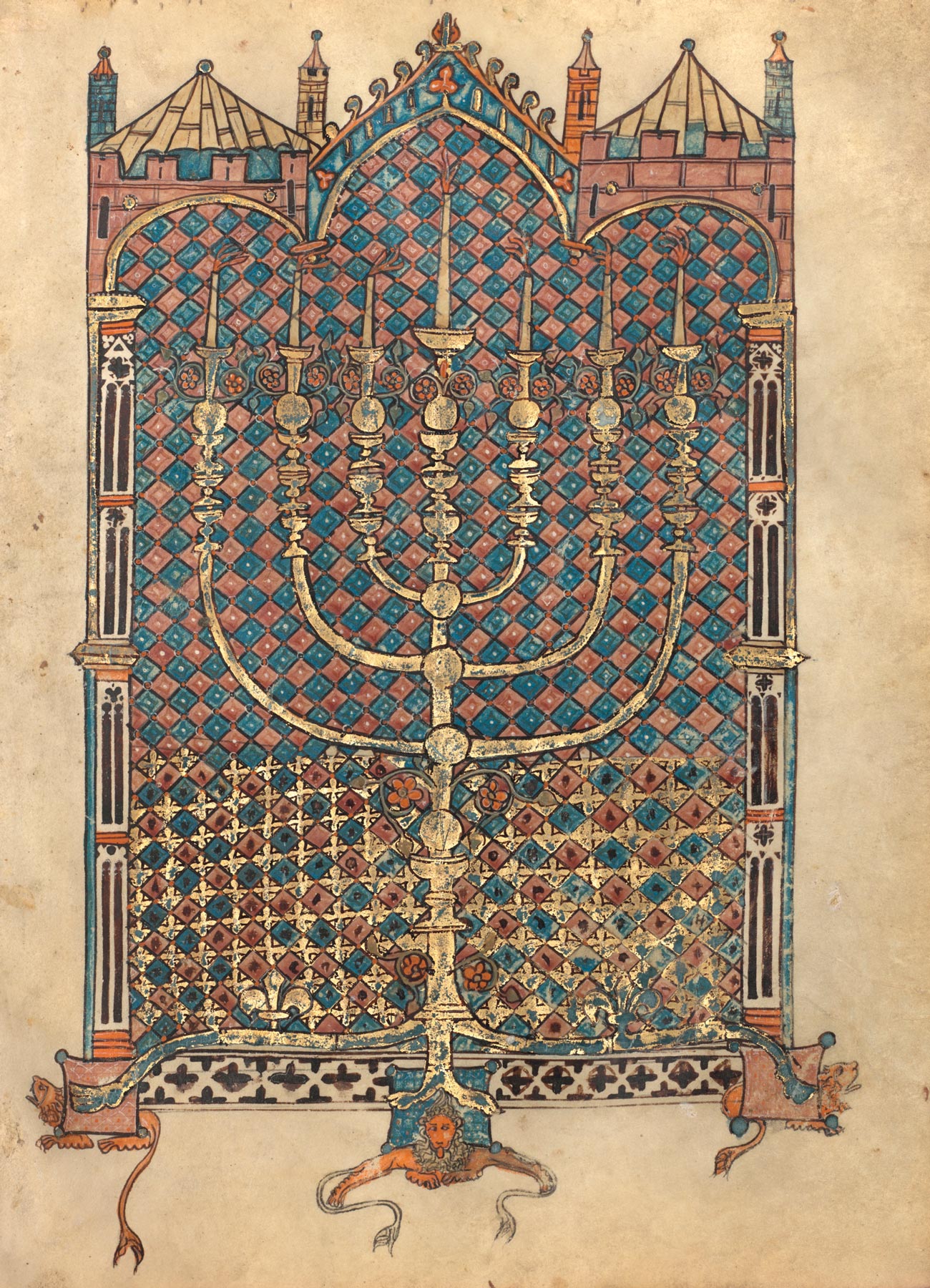

Menorah of the Tabernacle from the Rothschild Pentateuch, 1296, made in France or Germany. Ink, gold, and tempera colors on parchment, 10 13/16 × 8 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 116, fol. 226v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

The 54 weekly divisions (parashiyot) of the Torah are heralded by ornate text panels whose letters glimmer against tapestry-like backgrounds while fantastical beasts, animal-human hybrids, and plant forms weave intricate patterns across the page. The letters themselves are often the foundation for the illumination, with ornamental initials and words—gilded or in brilliant colors—dominating the page.

Decorated Text Page from the Rothschild Pentateuch, 1296, made in France or Germany. Ink, gold, and tempera colors on parchment, 10 13/16 × 8 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 116, fol. 178v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

On other pages, the letters serve as platforms for lively figures to fight and play.

Decorated Text Page from the Rothschild Pentateuch, 1296, made in France or Germany. Ink, gold, and tempera colors on parchment, 10 13/16 × 8 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 116, fol. 206v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Decorated Text Page from the Rothschild Pentateuch, 1296, made in France or Germany. Ink, gold, and tempera colors on parchment, 10 13/16 × 8 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 116, fol. 150. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Sometimes the stately decoration emphasizes the serious and sacred nature of the text.

Decorated Text Page from the Rothschild Pentateuch, 1296, made in France or Germany. Ink, gold, and tempera colors on parchment, 10 13/16 × 8 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 116, fol. 435v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

In other cases, the charm of the image comes from the scenes portrayed, such as one in which a multi-legged dragon has partially swallowed a hapless bystander whose legs still protrude from his mouth.

Decorated Text Page from the Rothschild Pentateuch, 1296, made in France or Germany. Ink, gold, and tempera colors on parchment, 10 13/16 × 8 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 116, fol. 162. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

At the top and bottom of each page, the Mesorah Magna, comprising notes about textual details such as the spelling of individual words, is executed in micrography, minute Hebrew letters often formed into elaborate shapes. They take form of geometric designs, staircases, or even animals.

Text Page from the Rothschild Pentateuch, 1926, made in France or Germany. Ink, gold, and tempera colors on parchment, 10 13/16 × 8 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 116, fol. 104v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Decorated Text Page from the Rothschild Pentateuch, 1296, made in France or Germany. Ink, gold, and tempera colors on parchment, 10 13/16 × 8 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 116, fol. 188v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Seven Centuries of Provenance History

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Pentateuch is the amount of information we have about its history and provenance. For most manuscripts in the collection, we are lucky to know a few names of past owners, usually starting in the modern era. For example, the Christian Bible (Ms. Ludwig I 13) on display alongside the Pentateuch in Art of Three Faiths was created for the Cathedral Library at Cologne in the fifteenth century. In the eighteenth century, it was found at the Library of Schloss Nordkirchen in Germany, and in the early twentieth century, the Dukes of Arenberg owned it. By 1960, it had passed to the collection of Otto Schäfer, followed by the collection of Peter and Irene Ludwig, and then it came to the Getty in 1983.

We have even less information about the Qur’an pages (Ms. Ludwig X 1) in the exhibition. The manuscript to which the pages originally belonged was possibly made for the Great Mosque of Kairouan in the ninth century. Although the manuscript may have stayed at the mosque for centuries, we don’t know anything specifically about the set of pages until it was potentially connected to Sultan Mahmud II (1785–1839). The Getty Museum acquired the pages in 1983, also via the collection of Peter and Irene Ludwig.

By contrast, the Pentateuch contains a wealth of information that allows us to piece together its travels over the centuries. Dr. Menahem Schmelzer generously shared his in-depth knowledge of the manuscript’s history with the Getty, and his research is largely reflected in the following account of its history.

First, the scribe of the main text added his name, Elijah ben Meshullam, and the date he completed the text: June 17, 1296. He also recorded the name of the patron, Joseph ben Joseph Martel.

Text Page from the Rothschild Pentateuch, 1296, made in France or Germany. Ink, gold, and tempera colors on parchment, 10 13/16 × 8 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 116, fol. 583v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

The scribe who completed the micrography added his name as well: Elijah ben Jehiel.

Text Page from the Rothschild Pentateuch, 1296, made in France or Germany. Ink, gold, and tempera colors on parchment, 10 13/16 × 8 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 116, fol. 224v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Unfortunately, no further historical records about any of these individuals have been found, but future research could uncover more about them. Yet evidence in the text suggests the patron or scribes were originally from England but lived in France. The Jewish population of England was expelled by royal decree in 1290, so this manuscript, which was created six years later, may reflect the reality of relocated Jewish emigres in France. The illumination, in turn, was executed in France or Germany (further research may also prove fruitful in this area), perhaps reflecting the continued movement of exiled Jews, as Jewish people were expelled from France in 1306.

The next indication of the manuscript’s travels occurred in the fifteenth century, by which time the Pentateuch had moved to Italy. After 1484, members of the Rapa family owned it, and they added an inscription to that effect.

Colophon from the Rothschild Pentateuch, 1296, made in France or Germany. Ink, gold, and tempera colors on parchment, 10 13/16 × 8 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 116, fol. 584v. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

During the Pentateuch’s time in Italy, one of its pages was skillfully replaced. The most famed Jewish scribe-artist of the period, Joel ben Simeon (active in the second half of the fifteenth century), replicated the text and added an illumination. His color palette and style reflect a Renaissance aesthetic.

Decorated Text Page from the Rothschild Pentateuch, 1296, made in France or Germany. Ink, gold, and tempera colors on parchment, 10 13/16 × 8 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 116, fol. 478. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

By the sixteenth century, the manuscript belonged to Saul Wahl (1541–1617) of the famed Kazenellenbogen family of rabbis in Poland. According to folklore (although some historians affirm that there is truth to the story), Saul Wahl served as temporary King of Poland for one day, while members of the nobility decided who would inherit the throne. In that brief reign, he supposedly passed many laws designed to benefit the Jewish people of Poland, and he was thereafter called “Wahl,” which means “election” in German.

By the early twentieth century, the manuscript had made its way into the collection of Adelaïde, Baroness Edmond de Rothschild, a member of perhaps the greatest family of collectors the world has ever known.

Bookplate of the Baroness Edmond de Rothschild from the Rothschild Pentateuch, 1296, made in France or Germany. Print in ink on paper. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 116. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

At some point before 1920, she donated the manuscript to the Stadtbibliothek at Frankfurt. The library not only marked the manuscript with a number indicating its place in the collection—“Ausst. 5”—but also pasted in a piece of paper for the signatures of those who studied the manuscript. This practice was common in the early twentieth century and is probably still known to members of our audience who remember signing out books at libraries before the advent of computers.

Inserted record of readers from the Rothschild Pentateuch, 1296, made in France or Germany. Ink on paper. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 116. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program

Only two signatures are recorded on the sheet. The first is that of Rachel Wischnitzer, who saw the manuscript on November 19, 1936. She has an incredibly interesting story herself, being one of the first three women in Europe to earn an architecture degree from the Sorbonne in Paris. After moving to Berlin in 1928, she became the art and architecture editor for the Encyclopedia Judaica and a curator at the Jewish Museum. She also specialized in the art history of Hebrew manuscripts, which no doubt inspired her visit to Frankfurt. Fortunately, she escaped from Nazi Germany in 1938 and relocated to New York, where she established the Fine Arts Department at Stern College for women. She died in 1989 at the age of 104. (Dr. Katherine Sedovic, a former graduate intern in the Department of Manuscripts, provided invaluable research on Rachel Wischnitzer.)

The second signature on the recording sheet dates from November 5 to 6, 1941, and belongs to Dr. Fritz Zschaeck, a medievalist attached to the Institut zur Erforschung der Judenfrage (Institute for the Research of the Jewish Question). The institute supported the Nazi persecution of Jews in Europe by collecting information about the Jewish people and providing a method of gathering looted Hebrew manuscripts.

The Pentateuch survived World War II intact. In 1950, the manuscript was part of an exchange between the German government and a Jewish family for land in Frankfurt that had been seized during the war. The family had settled in New York but eventually immigrated to Israel. The Getty Museum acquired the manuscript directly from this family in 2018.

Embodied History

The storied history of this object thus presents the most remarkable provenance narrative of all the manuscripts in the Getty’s collection. Moreover, following the movement of this remarkable manuscript across time is akin to mapping the diaspora of the Jewish people over the past seven centuries. The Rothschild Pentateuch demonstrates how an artwork can carry meaning across geography and chronology to become a concrete embodiment of history.

We invite you to join us in admiring this awe-inspiring, incredibly beautiful testimony to the efforts of hundreds of years of caretakers who protected and cherished the manuscript, often through periods of great upheaval and conflict. The Getty is honored to become the most recent link in a long chain of custodians of this treasure and to play a role in preserving it for generations to come.

Are there some early English translations of the text that can be looked at on the internet?

Great information. Great exhibit.