As I walked through the manuscripts gallery at the Getty Museum, I yearned to reach out and turn the pages of the magnificent illustrated books on view. What images or hidden narratives might be pressed between those parchment pages? What inspiration or personal memories might I draw from those visual stories?

Although my life story may seem far removed from the pages of illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, I couldn’t help but see connections. When I visited, the exhibition on view was Traversing the Globe through Illuminated Manuscripts, which featured painted book arts from Europe, Africa, and Asia. I grew up in rural Washington and joined the U.S. Coast Guard at the age of 21. Over the course of my five-year enlistment, I traveled to South Korea, Guam, American Samoa, Saipan, Kuwait, Iraq, and many islands in the South Pacific, and I have continued to travel in the years since.

A younger me in the U.S. Coast Guard

The illuminated manuscripts in the exhibition, depicting battles, saints, monsters, and foreign peoples and lands, brought back personal memories and made me wonder how future generations will interpret the images of war and religion from our own age.

Connecting Past and Present

As an aspiring writer and amateur artist, my creative juices begin to flow when I see an illustrated book from Armenia or a group of tiles from Iran. The pairing below shares patterns and motifs (dragons and phoenixes from China), and I begin to wonder how future generations will decipher the cross-cultural images that we produce today. What can artworks from a bygone age reveal about the connections between distant cultures and their lasting impact on the history of the world?

Saint John and Decorated Text Page in a Gospel Book, 1386, Petros (scribe), made in the Lake Van Region. Tempera colors on paper. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig II 6, fols. 197v–198; Star and Cross Tiles, probably Takht-i Sulaiman, Iran, about 1270–80, fritware overglaze painted with colors and gold. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Shinji Shumeikai Acquisition Fund (AC 1996.115.1-4)

In the exhibition, I saw how deeply our ideas about trade, religion, civilization, and other cultural phenomena are affected by history and cross-cultural exchange. The Iranian star and cross tiles (about 1270–80) reminded me of a schoolhouse in Iraq that we used as a training facility during the latter years of Operation Iraqi Freedom. Featuring gold Chinese dragons and phoenixes set against a blue background, the tiles were reminiscent of the art and architecture I saw during my time mentoring Iraqi troops in Umm Qasr.

War and Peace

Moses Defeating the Moors (detail) from Rudolf von Ems’s World Chronicle, about 1400–10, German. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 33, fol. 66v

Many of the objects in the exhibition reflect both realities and fictions about times of war and peace. In an early-15th-century German World Chronicle, for example, the biblical figure of Moses fights an army of Kushtite-Ethiopians who wear armor from the Renaissance era, employed as a way to connect early modern readers with the distant past.

Another beautiful, if violent, set of images comes from the Shah ‘Abbas Bible, also called the Crusader Bible in reference to the book’s creation in the 13th century likely for the French court of the crusader king, Louis IX. It contains depictions of love, envy, hate, rape, and murder alongside scenes from everyday life. Even in times of war or strife, life goes on. Farming, commerce, raising children, and going to church all continue. I witnessed this myself in Iraq. The period of time where our two countries were fighting against each other had long passed by the time I got there, but the ghosts of a war torn country still remained, including burnt out vehicles and anti-American graffiti.

Scenes from the Life of Absalom from the Shah Abbas Bible, about 1250, French. Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig I 6, verso

Remembering Recent History

Looking at these violent images of biblical scenes brought back memories from my times abroad when I encountered relics of more recent historical events, such as coming across sunken tanks off the coast of Guam, digging my hands into the sand and pulling up .50 caliber machine gun shells that had sat unearthed for 60 years, or standing on the deck of a 1,000-foot oil tanker left over from the Gulf War and half-sunken into the Persian Gulf. How will these sights, along with the other things that I’ve seen, done, read, and written, be interpreted several centuries from now?

What can anyone say that history hasn’t already shown us? In the premodern manuscripts in the Getty’s collection, I saw how the histories of our world are both connected and fractured, and it reminded me of the contradictions I have witnessed in my own experiences. Humans can be both utterly violent and brilliantly creative, and both destructive acts and beautiful creations can emerge in the name of religion.

The author in the Persian Gulf. Photo: Alec McPike. All rights reserved

As I have learned from my journeys, travelers are enriched through encounters with new people, customs, histories, and ideas about what it means to be “global.” I have an insatiable love of exploration and a curiosity for making new discoveries about our world, both past and present.

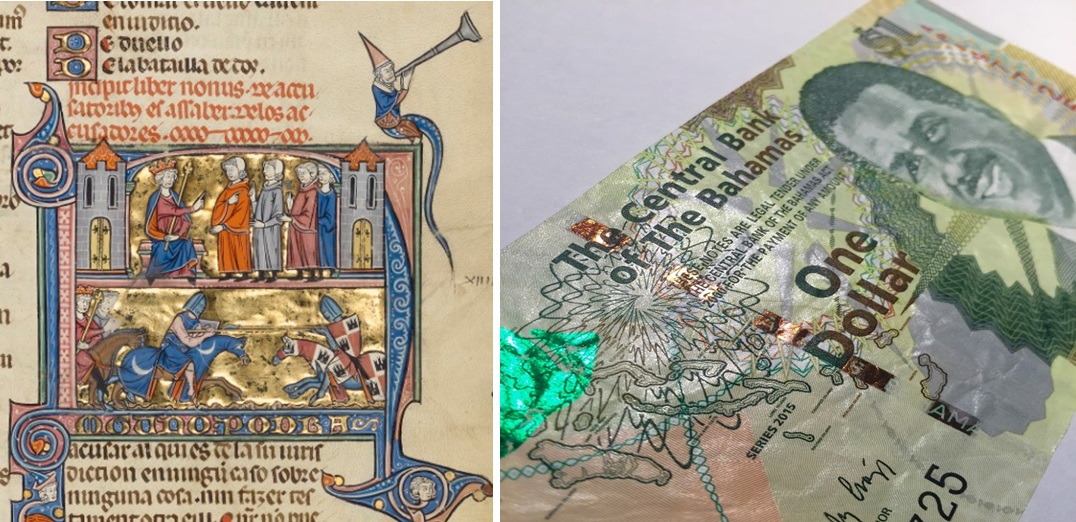

In Traversing the Globe through Illuminated Manuscripts, I made many such discoveries. I saw the connection between images of political authority in a 13th-century Spanish manuscript and Bahamian currency today – where rulership, race, and religion appear intertwined – and between maps drawn in the decades after Christopher Columbus’s voyages and our own Google Maps.

Initial N: A King Speaking to Four Men and A Joust between Two Knights from Feudal Customs of Aragon, Northeastern Spain, about 1290–1310, tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig XIV 6, fol. 255; Bahamian currency (photo: Alec McPike)

How will future generations remember the recent past and quickly fleeting present of today? We have much to learn from history, and the beautifully preserved pages of these illuminated manuscripts can help guide the way.

Great article. thanks from someone in rural Western Washington. Visiting in early November, can’t wait to see the Getty again

As an artist and calligrapher, I have done research over the years on medieval illuminated manuscripts.

They are some of the most beautiful art ever done, especially French manuscripts such as: (The Duke de Berry’s Tres Riches Hours).

I enjoyed your article.