Conservator George Bisacca from the Metropolitan Museum of Art working on a panel. Image courtesy of the Museo del Prado

In 1507, German Renaissance painter Albrecht Dürer painted life-size figures of Adam and Eve, defining their forms with a fluid and continuous line. These spectacular oil-on-panel paintings, which have just undergone a lengthy conservation, went on display again last week at the Prado Museum in Spain for the first time in two years, and the results are magnificent.

Work on the panels was recently completed by a team of international experts supported by a Getty grant. The Getty Foundation funded the restoration of the delicate panels as part of the Getty’s Panel Paintings Initiative, a collaboration between the Getty Foundation, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the J. Paul Getty Museum. The grant was given to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, whose experts worked with the Prado’s conservators.

To illustrate the complex process of restoration carried out on both panels, these paintings are on display for four months in a special exhibition space at the Prado that showcases the front and back of the panels. In an adjoining gallery, the conservation of the two panels is explained in detail through several text and image panels that include reflectographs and x-radiographs of the works.

Paintings created on wood supports—panel paintings—rank among the most significant works of Western art made from the 12th century onward, and today constitute a major part of American, European, and Russian museum collections. Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa was painted on a poplar panel, for example. Panel paintings’ unique structure and the complex aging behaviors of wood and paint, however, have long challenged conservators, and today few experts have the diverse skills and experience necessary to conserve these types of paintings.

That means that significant paintings on wood panels will be at risk in coming decades due to a scarcity of conservators with the highly specialized skills required to work on these complex works of art. The Panel Paintings Initiative, which focuses on training new conservators to fill this void, is a response to this problem.

This project with the Met and the Prado was a fantastic opportunity—the conservation of two great works of art, and hands-on training for a number of conservators, including one from the the National Museum of Budapest and our own Getty Museum, to learn from some of the most accomplished conservation experts in the world.

The challenge was complex. Over the course of their history, the paint surfaces of the Adam and Eve panels had undergone successive restorations that accumulated, one on top of the other. These old restorations affected the panels, particularly that of Adam.

In early interventions on Adam, the thickness of the panel itself had been reduced in order to attach a rigid structure to its back. The Eve panel previously had three cross-bars nailed to it from the front to eliminate its natural curvature, with the goal of making the panel lie flat, common practice for the last 200 years. But the inevitable movement of wood—which expands and contracts—meant that these “supports” actually created distortions and bulging that in turn created shadows and irregularities on the paint surface. The front of the panels had both been treated with varying types of varnish.

These well-meaning past interventions resulted in very flat-looking paintings. Thick layers of dirt, oxidized varnishes, and areas of repainting that had darkened over time now concealed Dürer’s brushstrokes and the painting’s delicate original coloring. Restoration was considered necessary, and two years ago, a group of experts began the process.

The old cradle (a wooden grid stuck to the back of the original panel) was removed from Adam and the numerous cracks it had produced were closed up. (This required the insertion of some 388 finely shaped wedges to repair the numerous splits!) Due to the fragility of the panel, a new reinforcing structure respecting the natural curvature of the wood was carefully attached to the original panel, allowing it to move freely. On Eve, the three screwed-on cross-bars were removed and the original, surviving cross-bar was restored and laminated in order to adapt it to the natural curvature of the panel.

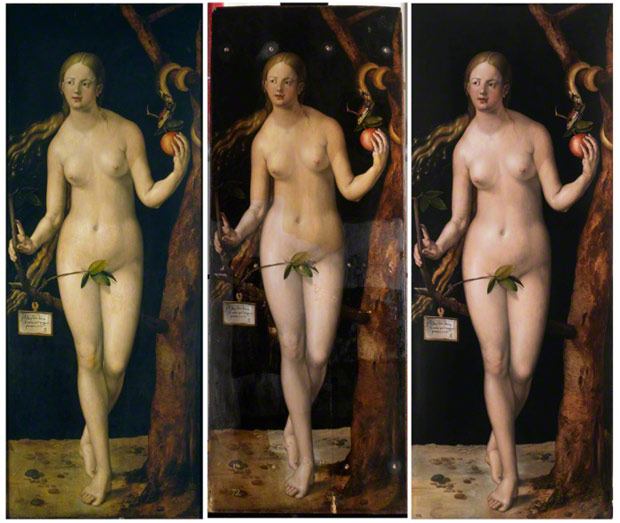

Having stabilized and given the panels smoother, more continuous surfaces, work started on the delicate, complex task of restoring the paint surfaces. This work, done by a skilled Prado conservator, involved eliminating the incorrect contrasts and modifications. It was difficult work requiring immense skill, and you can see the astounding difference in the pictures below.

Dürer’s Adam (above) and Eve before, during, and after conservation.

Despite the undeniable importance of the two paintings, it’s interesting to note that for 283 years (with the exception of the brief reign of José Bonaparte), since their arrival in Madrid in 1655, both panels were considered to be “nudes” and therefore not for public consumption. They were kept in spaces not open to the public. The very fact that they have survived at all is somewhat miraculous—in 1762, Charles III’s moral qualms led him to include them on a list of “indecent” paintings to be destroyed. (Apparently, the intervention of the Court Painter Mengs saved Dürer’s panels—he was able to convince the monarch that both paintings were useful for his pupils to study.)

The paintings entered the Prado in 1827, and were incorporated into the display of works on view to the public in 1838. And today, they are on view again, to the delight of visitors. But it took a lot of collaboration and behind-the-scenes work to finally allow Dürer’s gorgeous artistry to shine through again.

You can view a video of the rehanging of Adam and Eve on the Prado’s website here.

Bravo! Remarkable conservation work on the stunning Durer panels. I enjoyed the Prado video as well.