Danaë, 1621–23, Orazio Gentileschi. Oil on canvas, 63 5/8 x 89 1/4 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2016.6

One of the most accomplished Italian artists of the early 17th century, Orazio Gentileschi, executed a monumental painting representing the story of one of the most versatile figures in the history of Western art: Danaë.

The Getty Museum recently acquired Gentileschi’s picture, created between 1621 and 1623, in which Cupid pulls back a dark green curtain, allowing Jupiter, in the guise of a shower of gold coins and ribbons, to enter Danaë’s room. Danaë lies on a sumptuous bed of white and gold sheets, welcoming her fate by reaching up to the golden deluge. Starting today the painting is on view at the Getty Center.

A Trio of Love Paintings

The artwork was originally part of a group of paintings commissioned by the Genoese nobleman Giovanni Antonio Sauli, which includes a Penitent Magdalene (ca. 1622–23), today in a private collection, and Lot and His Daughters (ca. 1622), owned by the J. Paul Getty Museum since 1998. The subjects of the Sauli paintings come from disparate sources: Danaë is a figure from classical mythology, the story of Lot and his daughters is from the Hebrew Bible, and the Penitent Magdalene is from an apocryphal Christian tale.

The uniting thread between the three paintings is the relationship between women and God. Each artwork represents a different type of love: Danaë represents sensual love; the Magdalene symbolizes devotional love in the wake of her conversion; and Lot’s daughters personify the moral challenges of love, for they must choose between the sin of incest and a divine order to procreate after the men of Sodom are killed in the city’s destruction.

Early Views of of Danaë

Red-figure krater with Danaë (detail), Greek, ca. 450–425 B.C. Terracotta, 23 cm high. Louvre Museum, Department of Greek, Etruscan and Roman Antiquities. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The story of Danaë has been a popular one in the history of Western art. According to ancient sources, Danaë’s father, King Acrisius of Argos, learns of a prediction that he will meet his death at the hand of his grandson, so he imprisons his daughter, the princess. Mortal men cannot reach Danaë, but Jupiter, the god of sky and thunder, devises a method to satisfy his lust. He transforms himself into a rain of golden droplets, showering Danaë and impregnating her with the hero Perseus.

For centuries, the imagery of myth provided a common ground for understanding. Audiences were familiar with the stories and could immediately identify situations and characters. But the meaning of ancient myths often changed over time, and the same story could sometimes embody contradictory interpretations. This multiplicity of meanings is the case with the story of Danaë.

The first representations of the myth of Danaë are found on Greek Attic red-figure vases of the 5th century B.C. A krater in the Louvre features a partially nude Danaë lying on a bed in her chamber while receiving, with poise and dignity, the manifestation of Jupiter’s love. The meaning of this image is somewhat ambiguous: Danaë is a young, modest maiden surprised by the sudden arrival of a divine being, but she is also a woman ready to undress in front of her lover.

A Venal Woman

While Greek sources tend to associate the figure of Danaë with the generative power of the god, Roman poets portray her as a venal woman who sells her love in exchange for money. In one of his comedies, the Roman playwright Terence places a wall painting of Danaë in a courtesan’s house; it inspires the protagonist to follow Jupiter’s example by bribing his paramour with gold.

The lascivious interpretation of Danaë as a venal woman lasted for centuries, as a curious picture from 1799 by the French artist Anne Louis Girodet demonstrates. It is a satirical portrait of Anne Françoise Elizabeth Lange, one of the most successful actresses of the time, renowned for her talent, beauty, and wealthy lovers. When Lange refused to pay for an earlier portrait by Girodet, the incensed artist retaliated by painting a second portrait in which the actress appears as Danaë catching gold coins. The turkey wearing a wedding ring is a reference to Lange’s husband whom she married for his fortune, and the cracked mirror symbolizes her lack of self-perception.

Portrait of Mlle. Lange as Danaë, 1799, Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson. Oil on canvas, 23 3/4 x 19 1/8 in. Minneapolis Institute of Art, The William Hood Dunwoody Fund, 69.22. Source: Wikimedia Commons

A Virtuous Woman

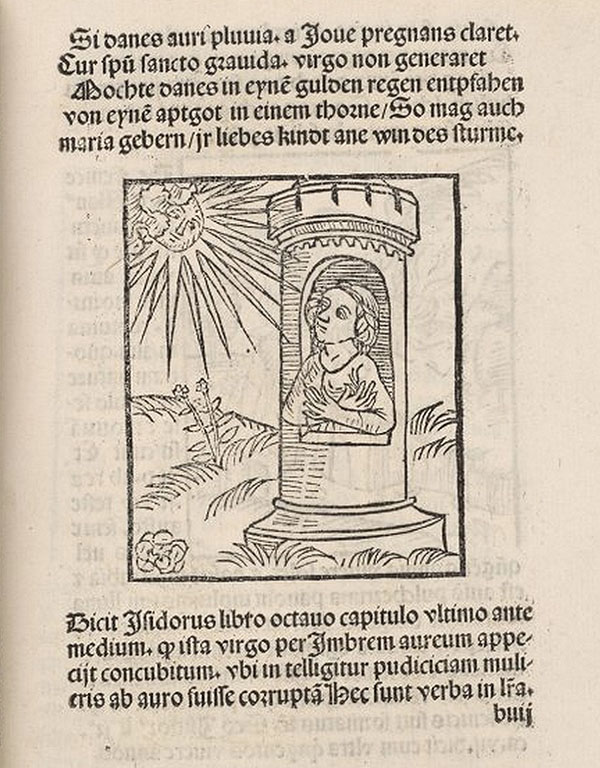

Like most classical myths, the story of Danaë became Christianized during the 14th century. She became a symbol of pudicitia, or modesty, and the tower protecting her virtue came to represent chastity. A woodcut from Franciscus de Retza’s Defense of the Inviolate Virginity of Mary (created about 1388) shows Danaë, fully clothed, sitting in a tower and receiving rays from Jupiter as the sun. The inscription below the woodcut states that if Danaë conceived a child by Jupiter disguised as a rain of gold, it was possible for the Virgin to be impregnated by the Holy Spirit.

Danaë in a Tower, ca. 1388, in Franciscus de Retza, Defensorium Inviolatae Virginitatis Mariae, ca. 1490. New York Public Library, Spencer Collection. Source: NYPL

A famous painting by Jan Gossaert from 1527 most explicitly fits within the tradition of the medieval pudicitia type. Here Danaë directly parallels the Madonna of Humility: she sits on cushions on the floor, wears a blue robe and delicate diadem, and her breast is exposed—all elements linking her with the lactating Mary.

Danaë, 1527, Jan Gossaert, called Mabuse. Oil on panel, 114.3 x 95.4 cm. Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen. Alte Pinakothek, Munich. Source: Wikimedia Commons

A Voluptuous Woman

The Christian interpretation of the Danaë myth sharply contrasts with the most widely read version in the Renaissance, contained in Giovanni Boccaccio’s Genealogy of the Pagan Gods, written between 1350 and 1375. The Italian writer remarked that Danaë deliberately chose a sexual liaison as a means of escaping the life of imprisonment enforced by her father. Boccaccio’s account leaves no trace left of the modest, chaste Danaë of earlier Christian writers.

The erotic overtones of the tale became central in celebrated paintings by Correggio and Titian in the 16th century. Titian created Danaë with Cupid for Cardinal Alessandro Farnese during his stay in Rome between 1545 and 1546. The completely nude beauty reclines languorously on a sumptuous bed, with her head resting on a pillow. In passive pleasure, she accepts the sensual experience, while Cupid rushes away with his unstrung bow on the right side of the picture. A contemporary observer, the poet Giovanni della Casa, wrote to the cardinal that Titian’s Venus of Urbino, painted few years earlier in 1538, looked like a nun in comparison to this Danaë, alluding to the erotic power of the new artwork.

Danaë, 1544–5, Titian. Oil on canvas. Capodimonte Museum, Naples. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In Ciceronianus (1528), Erasmus had these images in mind when he criticized paintings “where Jupiter slipping into the lap of Danaë through the impluvium attracts our attention rather than Gabriel announcing the conception of the Virgin.” His words still recognize the heritage of late medieval culture, but Danaë is no longer the symbol of the virginity of Mary—she is her rival.

The Danaë of the Erasmus’s interpretation is now entirely pagan, rounding out her journey as a figure of ever-changing meanings.

______

See Orazio Gentileschi’s Danaë, hanging alongside the artist’s Lot and His Daughters, at the Getty Center, Gallery E201.

Comments on this post are now closed.