Selections from the Man Ray materials acquired by the Research Institute. Clockwise from top right: Man Ray’s datebook from 1929; untitled self-portrait, before 1976; Man Ray in studio, 1950s; Man Ray’s datebooks from 1932, 1923, and 1939; undated portrait miniature. The Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.17. © 2011 Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Man Ray’s black and white portraits are widely celebrated, but two recent acquisitions by the Getty Research Institute shift the focus back on the famous photographer, providing a revealing picture of the often private artist.

The first acquisition, a compact but rich archive, contains hundreds of letters, over 50 photographs by Man Ray—some of them vintage prints—and the occasional unclassifiable object (a brass seal featuring lips, for one). For me, however, the most tantalizing aspect are a set of datebooks—27 years’ worth—that offer an intimate if abbreviated look at the expat artist’s daily life. Even a brief glance through the datebooks suggests why Man Ray so loved the artistic life in interwar Paris. The pages range in content from to-do lists to dates and times of photographic shoots.

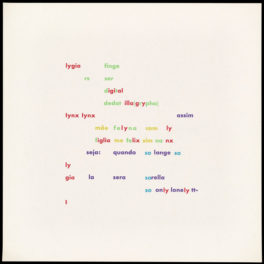

Names redolent of the era, such as Ernest Hemingway, Pablo Picasso, Elsa Schiaparelli, and André Breton, weave in and out of the pages, and indeed there are days that read like scenes from Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris. Best of all, they are punctuated by sketches and doodles that often show Man Ray daydreaming or testing out ideas.

A page from Man Ray’s 1939 datebook (January 2-8), featuring notes and sketches. At right, Man Ray sketched a horn topped with an eye and added the note trompe l’oreille. The Getty Research Institute, 2011.M.17. © 2011 Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

The second acquisition, meanwhile, contains a single datebook from 1953 that Man Ray used as a notebook throughout much of the 1950s. Through an unusual turn of events, the datebook now forms part of a portfolio of photographs taken by Gianfranco Baruchello of Marcel Duchamp, one of Man Ray’s closest friends and allies. The carnet shows Man Ray stepping out of his roles as photographer, painter, sculptor, and filmmaker to test his talent as a writer.

In addition to a brief text on Duchamp—which presumably explains its presence in the portfolio—Man Ray also worked at the art of the aphorism, playing around with phrases he clearly crafted as bons mots. They’re quirky, at times cantankerous—but also endearing:

This world would be more tolerable if people were as considerate of the living as they are of the dead.

I shall always oppose the cauliflower with the artichoke. The cauliflower is like a brain. The artichoke is a green rose—with a heart.

If you have nothing to say, if you are not creative, try politics.

We are creatures of spare parts, of accessories. There is no such thing in nature, where everything is built in.

There are two reasons for disliking a work—first because it is not understood, second because it is understood.

I’m looking forward to understanding (and liking) Man Ray further through these datebooks, which have been catalogued as part of the archive. Researchers have already begun mining its visual and verbal riches.

What a lovely presentation. This brief writing was ‘positively delicious’ — filled with MAN RAY tidbits of delight. After reading this, I shall never see an ARTICHOKE again but what I will think of his clever, beautiful lines-of-thought…

Thank You for providing this on line.

We are lucky enough to live in a big airy house on a cliff overlooking the sea on the Isle of Wight. It was previously owned by a good friend of Man Ray – Jacqueline Goddard – who was like a surrogate granny to me. When we moved in the house had been cleared by her family but under an old box at the back of a long disused room was an envelope with Jacqueline’s scrawl on the front. It read “Man Ray’s glasses’ and inside was a pair of plain black spectacles. In the office, holding down an old blind, a metal coat hanger bent to form a face in profile. It was magical to think he might have visited our home…. but I can’t find any evidence and perhaps Jacqueline was given the glasses when she went to Paris on her annual trip?